Last July, I spoke with Sky H., a 20-year–old who identifies as non-binary and grew up in a very conservative rural town in the Black Belt region of Alabama. In school, Sky received abstinence-only education. Sky told me there was little instruction about sexual and reproductive health besides the basics of reproduction.

After years of pain, Sky was diagnosed at age 18 with endometriosis, a painful disorder that can lead to fertility complications. The condition might have been diagnosed much earlier if they had learned more about their own bodies and reproductive health in school, Sky believed.

Unfortunately, Sky’s experience isn’t unique. Over the past year and a half, I’ve spoken to more than 40 young people from 16 counties throughout Alabama who also didn’t learn about their sexual and reproductive health in school. Like Sky, they missed out on critical information and described the negative impact this had on the choices they made and their health as they grew older.

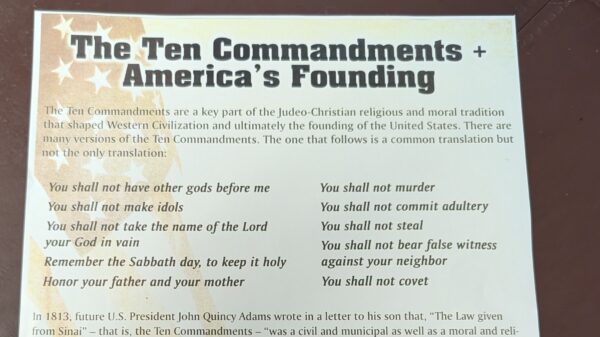

Schools in Alabama are not required to teach about sexual health but if they do, the State Code mandates a focus on abstinence. The State Code also contains stigmatizing language around same-sex activity and prohibits schools from teaching about sexual health in ways that affirm lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) youth. This makes it even harder for young people like Sky to get information.

But Alabama is not alone. Sixteen other states in the U.S. also do not mandate sex education in schools. And at least five others have laws stigmatizing same–sex activity.

Comprehensive sexuality education can improve health outcomes for young people. It can help them learn about their bodies and how to recognize abnormal gynecological symptoms, steps they can take to prevent and treat sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and other dangers to their health, and where they can go for reproductive health services.

Sex ed can also educate young people about the human papillomavirus (HPV) — the most common sexually transmitted infection in the U.S. — and how to lower their risk of HPV-related cancers through the HPV vaccine.

This information can improve young people’s health and save lives. Yet so few young people in schools throughout Alabama — and the U.S. — receive it. Instead, like Sky and other Alabama students, many young people receive abstinence-focused education.

These programs withhold critical, science-based information young people need to make safer decisions on their sexual health. They also shame adolescents about their sexuality, often leaving young people uncertain about who they can talk to or where they can go for accurate information about sexual behavior and health.

The problem is both a lack of political will and of adequate funding. Discriminatory property taxes and an inequitable education system leave many school districts in rural and less wealthy regions of Alabama without adequate funding. This means that programs considered optional, like sex ed, often aren’t offered.

Alabama, a state with high rates of sexually transmitted infections and cancers related to HPV needs to do more to address historic inequalities and state neglect that have left Black people at a higher risk of poor health outcomes. Mandating comprehensive sexuality education for all of the state’s schools — and allocating state funding for these programs — would be an important step forward.

Students in underfunded and neglected school districts — many of whom are Black and living in poverty — often lose out on access to critical and lifesaving information. It keeps them from being able to make informed and safe decisions and can harm their health. This unequal access to information can create lifelong disadvantages and may contribute to racial disparities in health as young people age into adulthood.

The Black Belt region of Alabama, where Sky is from, has high rates of poverty and poor health outcomes. The Black Belt region also has high rates of sexually transmitted infections and the highest rates of HIV in the state. Yet schools in this rural and marginalized region of the state are persistently underfunded.

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought glaring attention to systemic inequalities and racial disparities in health, including in Alabama, where Black people are significantly more likely to die from the virus than white people. Within the United States, we continue to see the disproportionate toll the pandemic has taken on Black people, who are more likely to live in poverty, lack access to health insurance, and suffer from chronic health conditions that put them at a higher risk of adverse health outcomes from the virus.

The pandemic has highlighted the importance of ensuring that everyone has the information, tools, and resources they need to make informed decisions to protect their health. Schools in Alabama — and across the country — should help do that for all young people.

The pandemic is also showing us what happens when discrimination and neglect leave certain people out.