Hundreds of Huntsville residents have sent written comments to the group tasked with reviewing police actions against protesters in June, with a week left to submit through the online community input portal.

The 10-member Huntsville Police Citizens Advisory Council has received almost 650 form submissions and more than 200 emails since the portal opened on July 9. It will close on Aug. 7.

Some residents have been frustrated that the form does not allow for uploads of photos, videos or other media. Many have footage, photos of injuries, Powerpoints and other documentation they want to share.

David Little, who is a member of the HPCAC, said it is considering how to accommodate digital media. There will be listening sessions for public comment but dates and locations have not been set. The group has discussed doing virtual meetings, but technology, logistics and cost may present obstacles, Little said.

All HPCAC members are volunteers and some have day jobs, said Little, a financial advisor. Some are retired and some work part-time. With hundreds of hours of body camera and drone footage to review, written testimonies to be read, public meetings to be held and research to be done, there is no projected timeline for the process and no deadline for the report.

It might take weeks or months, Little said, but he wants people to know the group takes its role seriously.

“We feel the pressure, believe me,” he said.

An intermediary between police and community

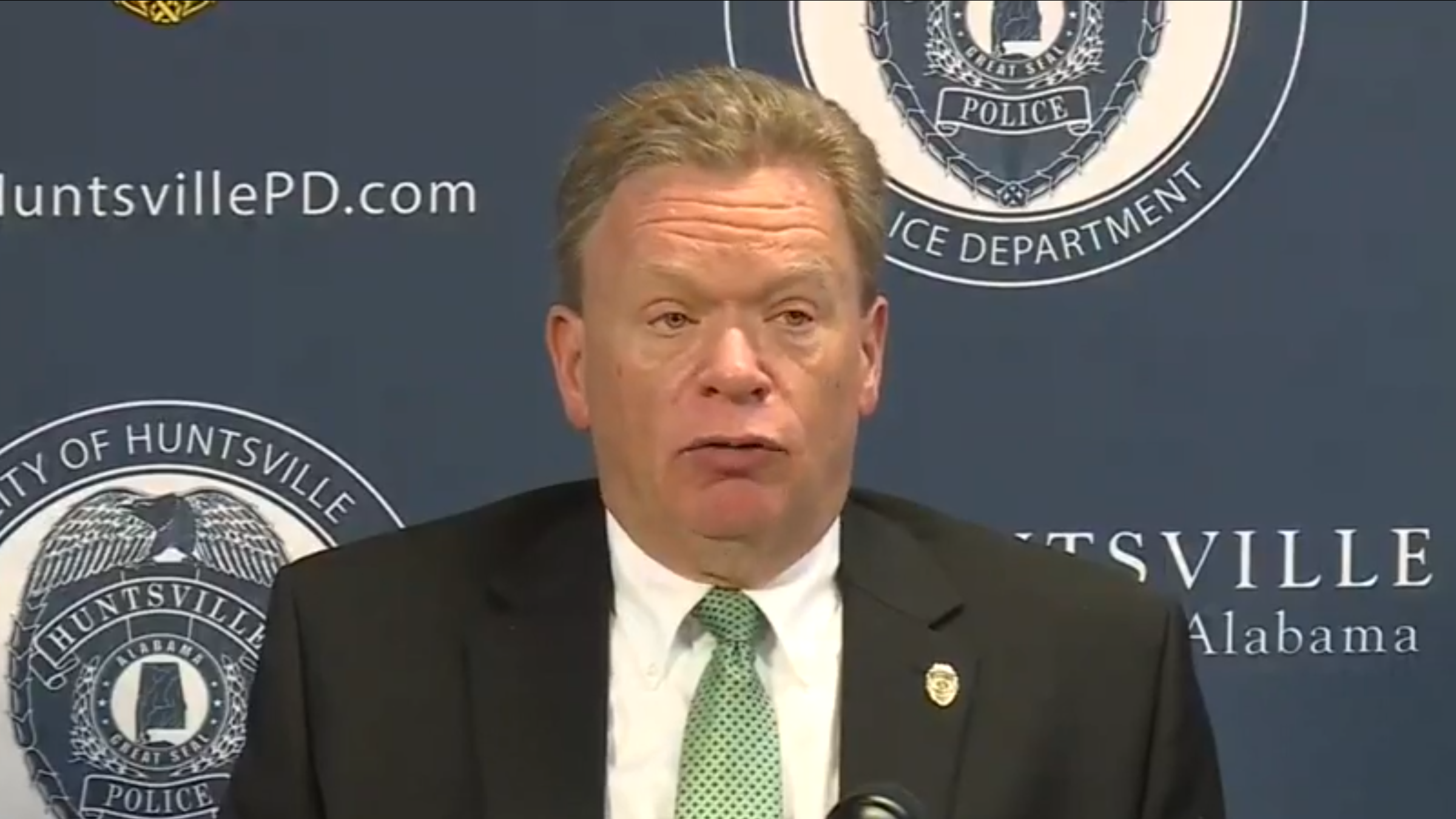

Little was appointed to the group when the City Council established it in 2010. Its first chair, John Reitzell, also remains a member. Both were appointed to their current two-year terms by Huntsville Police Chief Mark McMurray. The chief appoints three members, the mayor appoints two and the five city council members each appoint one.

The HPCAC was formed to improve communication and strengthen bonds between the police department and its community.

“The thing I usually tell people is that we bring a citizen’s perspective to policies and procedures of law enforcement,” Little said.

According to the city’s code, the group “shall be comprised of citizens who are concerned about police and community relations, and who are sensitive to community needs and perceptions” and who “represent the community at large.”

Former Councilman Richard Showers initially proposed it as a citizen review board that would review police actions and present findings, AL.com reported at the time. Showers was responding to community concerns that police were treating Black residents differently and that there was a lack of diversity on the force. Councilman Bill Kling proposed a different version that would give the department feedback on its policies and community relations but didn’t have a mandate to sit in judgment of individual officers, and a citizens advisory council was adopted.

Little was initially appointed by former Council President Mark Russell. The two were acquainted through Little’s involvement in the leadership training program Leadership Greater Huntsville.

Once the HPCAC was formed, its members spent several months visiting precincts and learning about every aspect of the Huntsville Police Department. They went on ride-alongs, met at the Huntsville Police Academy every couple of weeks and heard from members of each element within the department.

“We were just kind of drinking from the fire hose, learning as much as we could about the police department, about their policies, about how they operate,” Little said.

Since then, members have learned about police policies and procedures at the Huntsville Citizens Police Academy, at least until the pandemic began. Two new members were appointed in June and have not yet undergone that training.

The HPCAC used to hold four meetings each year. Barely any residents attended, Little said, so the meetings were cut to two per year.

“So that’s always been a real challenge, and I think maybe now all of a sudden everybody’s wanting to know who’s this advisory council, and maybe the community will be a little more engaged with us,” Little said. “That’s really what we want. It’d be great to have a full house wherever we meet.”

Concerns about independence

Chad Chavez did as police instructed on June 3 and went home after the NAACP rally permit expired. As such, he was not among the people who police fired at or hit with projectiles that night. He watched the chaos from the safety of his home, as the police chief has since stated was all anyone had to do to avoid what happened.

Yet Chavez, 36, a data analyst for a private healthcare provider, says that the actions police took in early June made him feel unsafe enough to take action. After watching things escalate on June 1, Chavez bought shatter-resistant goggles in anticipation of the protest two days later.

McMurray later cited protesters bringing protective equipment as evidence that they wanted a fight with police, but Chavez said he had no such desire. He was worried about losing an eye. At past demonstrations, he was used to seeing police chumming it up with marchers. This time was different. He saw officers “staring down” people who chanted or called for police to kneel. He told his goggleless fiance to get behind him if police started shooting at them.

“I think that’s a pretty good example of what the chief has done to make free-speech events pretty scary,” he said.

Chavez sent an email to the City Council on July 9 saying that he was concerned about how HPCAC seats are filled, with half appointed by a mayor and police chief who have both been dismissive of public outrage over protesters’ injuries and right to assemble. He also alleged a lack of transparency in the HPCAC’s review process.

“They seem to exist solely to reshare HPD’s social media posts,” he wrote. “Even a direct email generates a generic response of ‘your message has been received’ with no additional follow-up.”

He received an email the next day from HPCAC member John Reitzell, who thanked him for submitting a community input form and suggested that he may be given additional time at a future public meeting to present video footage. Reitzell then urged him to learn more about the HPCAC.

“Also you need to do some real research on us and what we have ACTUALLY done, and accomplished,” Reitzell wrote. “We are certainly not do nothings, we hold some non public meetings but most of our Executive sessions are not chronicled for obvious reasons. We have had multiple public meetings per year in each city council district for the 10 in which we have existed.”

Reitzell continued that the HPCAC has made a significant impact on the racial diversification of the department, on reforming “policies that made no sense to us” and advocating for procedures it deemed necessary to hammer into recruits at the academy.

The group has been consulted on issues large and small that the public wasn’t privy to, according to Little. Those include the implementation of body cameras and Tasers down to determining a fairer system for choosing what towing companies to call.

Chavez noted that when Little responds to comments on the HPCAC Facebook page, his profile picture is a blue line running horizontally across a black background, a common sign of support for police.

“In my mind the Blue Lives Matter thing has really come up in opposition to the Black Lives Matter thing, enough that someone who is claiming to be a representative of the entire citizenry is really sending a hostile message by making that their outward facing profile,” Chavez said.

Little maintains that a good relationship with the department is central to the HPCAC’s mission.

“A few people have said, ‘Oh, y’all are just a bunch of good ol’ boys, y’all are friends with the police.’ Well, you know, we wouldn’t be able to probably get a lot of stuff done and work with the department if we didn’t have a good relationship with them,” he said.

Expectations versus reality

Jonathan Rossow, one of the group’s newest members, said he understands residents’ fears about a too-cozy relationship.

“It’s a valid concern because by nature, the CAC has to have a working relationship with police if they’re going to be making recommendations,” he said.

Councilwoman Frances Akridge offered Rossow a vacant seat after he came to her with concerns about the police actions, including the posture they took toward protesters, he said.

Like Reitzell, a retired Army colonel, Rossow settled in Huntsville after a military career. He moved to the city about two years ago from Virginia after retiring as a colonel in the Air Force after 25 years and four combat tours.

Rossow said he retired from the Air Force but not from service to the country. He took an oath to defend the Constitution, a document he still reads, he said. He was dismayed by the destruction and looting that took place during many protests nationwide after George Floyd was killed, but said he is “very supportive” of the Black Lives Matter movement and thinks it necessary to move American society forward.

“I still believe that there are things and freedoms that are in the Constitution that members of our society, communities of our society — the African-American community — have yet to fully realize,” he said.

His role on the HPCAC, however, requires the impartiality and objectivity he exercised throughout his career, he said. That often required him to present uncomfortable things to people he had relationships with. If the relationship is good enough, it should weather those things, he said.

He’ll put his career experience to use throughout the review process, he said.

“I come at it from a military perspective, but more so as a military leader that’s been in combat and has been in the position of taking in information and making decisions,” Rossow said.

Little and Rossow both said they expect the review to result in recommendations for changes. Before the city council passed the resolution “to kind of give us teeth, so to speak,” HPCAC members met with the chief and asked pointed questions which McMurray answered, Little said.

Police want to do better and lessons will be learned from what happened in June, he said, but he wants the public to understand his council’s role. It doesn’t include employment changes, calling for the chief to be fired or the mayor to resign, he said — its task is to look at what police did, what if anything they can do differently and make recommendations about policy and procedure.

For comparison, the HPCAC has so far played a strictly advisory role in the case of HPD Officer William Darby, who is currently standing trial for murder for killing a suicidal man in April 2018.

AL.com reported that Darby testified that he pushed past two officers already on the scene, one of whom was talking to the man to de-escalate the situation, and shot the man in the face because the officer speaking to him was “failing to control the situation” and not “protecting herself.”

The man, Jeffrey Parker, 49, was sitting on a couch holding a pistol to his head, which turned out to be a flare gun that was modified to look real and fire buckshot. Darby claimed the man didn’t drop the gun after three commands to do so, and said he saw it move when Parker shrugged. The other officer, Genisha Pegues, testified against Darby, saying that Parker assured her he didn’t want to hurt her and she never felt threatened by him.

Darby was indicted four months after the shooting. That was three months after McMurray and members of the department’s command staff conducted an internal review and determined that Darby had acted within department policy, clearing him entirely. A few members of the HPCAC were invited to observe that review but were not able to vote on its outcome.

“In that step, we’re not there to be asking questions or casting blame or rendering a verdict,” Little said.

After such cases, the HPCAC will get briefed on any policy adjustments police decide to make and members may ask questions, Little said, adding that he couldn’t comment further on the Darby case because it is ongoing.

McMurray and Mayor Tommy Battle characterized the violence against Parker as unfortunate but warranted, as they have with the force used against protesters. Officers in both incidents did what they were trained to do.

According to city code, the HPCAC’s role is to advise on issues that include “Actions, philosophies, behaviors and practices that contribute to community tensions, grievances, and complaints,” but it is unclear how deep the group is prepared or equipped to go in its present mandate.

In general, Little said he thinks the department is ahead of the curve on many of the reform measures he hears politicians calling for in other parts of the country. Its academy requires 19 weeks of training compared to 13 weeks at the state academy. It trains officers in de-escalation, mental health and implicit bias.

Little said that the report could result in recommendations like better loudspeakers if protesters couldn’t hear commands to disperse or changes to policies regarding use of force during a multi-agency response.

“So maybe that’s something we work on, is: Ok, well, if something happens, how do we coordinate use of force decisions, because it’s the sheriff’s department that has rubber bullets, not the Huntsville Police Department,” he said.

Asked if the HPCAC can get information from the other agencies involved on June 3, Little said that the council has no oversight or official connection to them. He knows Sheriff Mark Turner from a leadership class they once took together, though, and could ask questions if the council has any.

“I don’t know why they wouldn’t answer them,” Little said. “But again, I don’t know if that would fall into our purview of the process when we’re a City-of-Huntsville-appointed board.”