We are descendants of Emma Sansom’s family and current or former members of the Gadsden community. We add our voices to the call to remove the statue at the head of Broad Street commemorating Sansom and Ku Klux Klan leader and Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest.

The monument was erected to enforce white supremacy in Gadsden, which we abhor and lament. The only defensible action today is to remove the statue.

Our community may have forgotten why this statue and others like it were erected. We must remember why in order to take wise action.

According to the Auburn University-supported Encyclopedia of Alabama: “Emma Sansom (1847-1900) played a heroic role in the Civil War, when as a teenager she led Confederate general Nathan Bedford Forrest across Black Creek in northern Alabama to capture Union colonel Abel D. Streight and his raiders in 1863.”

Sansom thus guided to victory the man who would become the first leader of the Ku Klux Klan as the United States struggled to establish a multiracial democracy.

Support of the Confederacy and white supremacy cannot be separated given the historical reality: an oligarchy of less than 400,000 enslavers brought about secession and war to guard their “property rights” over enslaved Black people. Alabama’s secession ordinance in January 1861 foregrounded the hope to “meet the slaveholding States of the South” and set up a new government. Cherokee County — which Gadsden was a part of in 1861 — voted against secession in that convention, as did St. Clair County and most northern Alabama counties.

This division among the white ruling class was an early sign of Confederate disunity as many Southerners resisted the Confederate project throughout the war. Thousands of Alabamians enlisted in the Union Army, mostly from northern Alabama where slavery was entrenched but less centralized than in the lower Alabama “black belt.”

Decades after Lee’s surrender to Grant at Appomattox Court House, the “Lost Cause” came into existence. The Lost Cause refers to the myth that a unified South fought for a heroic and noble civilization doomed by fate and the ahistorical “aggression” of the North. The elements that make up the Lost Cause draw from writings by Confederate President Jefferson Davis and by Confederate General Jubal Early in the 1870s and 1880s. They revised the history of secession and war to distance the Confederacy from slavery, focusing instead on antebellum South

Carolina Senator John C. Calhoun’s “states’ rights” philosophy — itself a platform to justify Calhoun’s support of what he called the “positive good” of slavery.

The purpose of the Lost Cause was to justify the enslaving oligarchy’s motives and mission in the minds of white Southerners, most of whom did not own slaves. Its cult conducts an enduring counter-revolution to deny Black people full citizenship to this day.

The legacy of the enslaving power is violence against Black people up to now. That violence includes the KKK’s multiple incarnations, the Jim Crow regime, thousands of lynchings, and repression against Black people struggling for civil rights. Today there are crosses burning in Alabama in reaction against the Black Lives Matter movement. The Lost Cause is not just a shameful past wound, its adherents oppress Black people in America to this day.

What motivated the white people of Gadsden to erect this monument to Sansom and Forrest is just one part of a larger project to retrench white rule and eliminate Black political freedom.

After federally-directed Reconstruction ended in 1877, the white ruling class regained political control of the Southern states. Democratic Party “Redeemer” governments passed Jim Crow laws segregating Blacks. The US Supreme Court decision Plessy v Ferguson in 1896 upheld Jim Crow segregation. From 1890 to 1908, almost every post-Confederate state including Alabama adopted a new constitution that disenfranchised the Black population.

The wave of post-Confederate activity was a direct cultural outgrowth of the repression wrought by Southern states against Black people as the Lost Cause cult took hold. This period birthed the “Dunning School” of historical thought that condemned Reconstruction as a corrupt mistake, a view modern historian Eric Foner calls “part of the edifice of the Jim Crow system.”

The United Daughters of the Confederacy, founded in 1894, was the most prolific organization building Lost Cause monuments. They also enlisted upper- and middle-class white youth and cultural institutions to carry the flame of the Lost Cause through highly influential educational campaigns including endorsing a book that lionized the Ku Klux Klan.

The year 1900, when various post-Confederate groups had their first national convention, began a massive wave of Confederate monument construction on government and publicly accessible property. The Southern Poverty Law Center identified 403 unique monuments constructed to the Lost Cause from 1900 to 1919, over half of all such monuments standing today.

In 1907, forty-four years after the Black Creek crossing, the Gadsden chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy put up the statue of Emma Sansom and Nathan Bedford Forrest overlooking the Coosa River. The Etowah County commissioners court, which today is the Etowah County Commission, also got the Alabama state Legislature to fund the statue. Public money paid for the establishment of this monument and the public must be involved in its disestablishment. This is not a private matter.

We should remember that the City of Gadsden’s establishment of this statue was only accountable to the white citizenry. Black people were unable to vote and enjoy representation during this time due to Jim Crow. It was not a unified city building this monument, but a segregated racial class directed by the torch-bearers of the Lost Cause. Viewing these statues in the context of history, it is clear that their purpose is domination of Black Americans struggling to secure their liberation.

The Sansom and Forrest statue is inextricable from the enslaving power and its twisted descendant ideologies. The statue’s base honorably depicts the man who oversaw the massacre of primarily Black Union soldiers at Fort Pillow which has been called “one of the bleakest, saddest events in American military history.” The public celebration of Forrest’s legacy is shameful, and Emma Sansom’s aid to his cause cannot be separated from its consequences. They supported enslavers against the liberation of millions of Black people.

The McNeel Marble Company of Georgia, which built the statue, clearly stated what it was selling in a Confederate Veteran article for its statues proclaiming “SUPREMACY.” The statue is not a contemporary historical marker; nor is it supposed to be a genuine likeness of Emma Sansom. Rather, the statue is a political provocation built only six years after Alabama’s constitutional change shifted the Jim Crow regime into overdrive. Its purpose has not faded. The statue’s memorial of Forrest and Sansom in 1907 is akin to erecting a statue to segregationist Birmingham leader Bull Connor today, a man who attacked civil rights protesters including children with dogs, fire hoses, and mass arrest in the early 1960s.

These monuments do harm lasting for generations when we forget the underlying causes of division and inequality in society. The roots of Black peoples’ oppression today have a lot to do with the erection and maintenance of that statue, as does the relatively wealthier position of white people in our community. To achieve justice, we must remember and then act in solidarity.

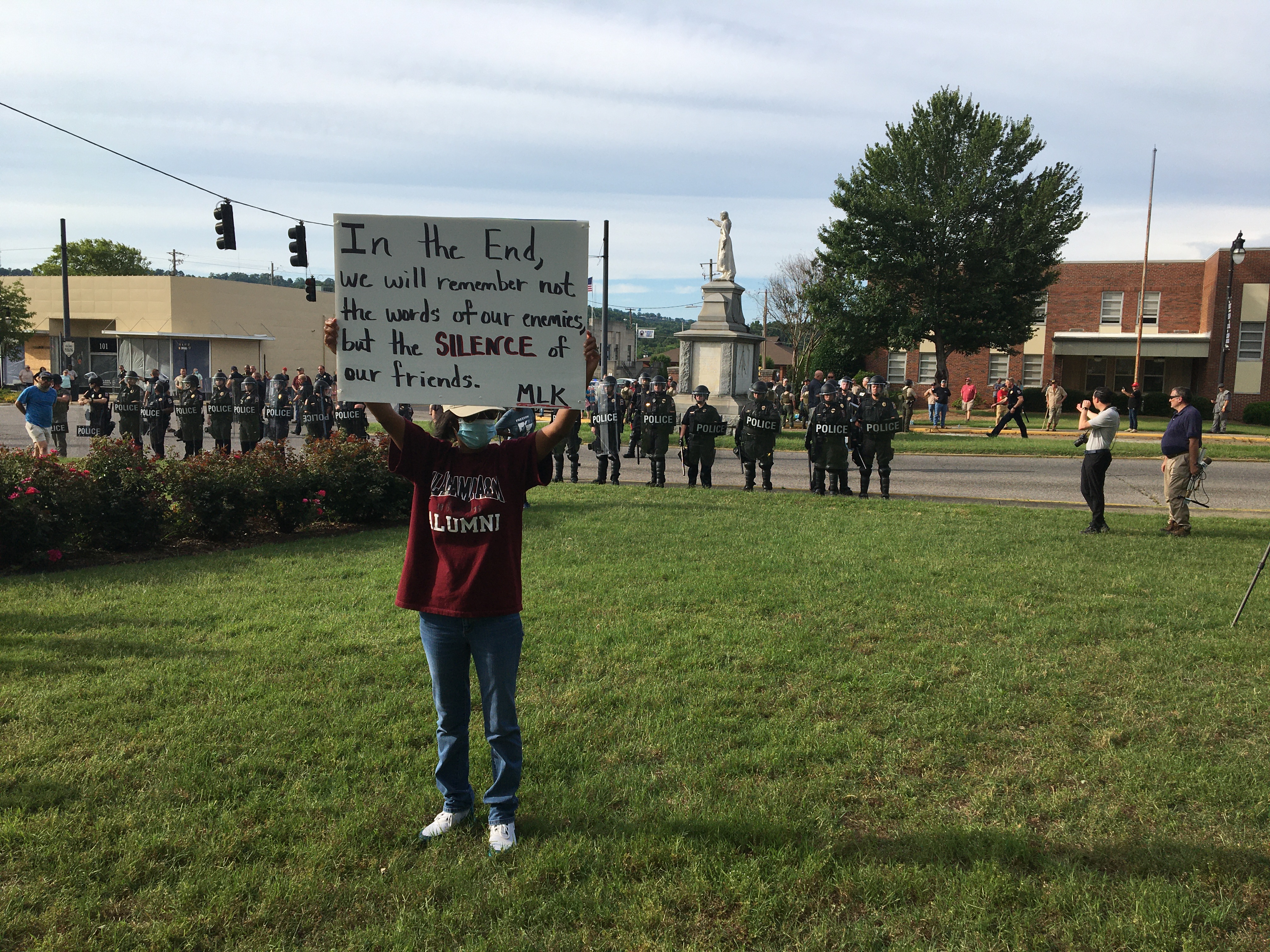

The multiracial movement calling for change in Gadsden is made up of our neighbors. They are not “outside agitators.” They have to live with the Lost Cause’s weight every day—as we all do.

Some white people in Gadsden say they feel a connection to this statue as part of their heritage, and consider the statue part of the fabric of their home. Our Black neighbors are making it clear that they agree, and that is exactly why they need to see change in our community. We want to live in a harmonious democratic society where all can live free of intimidation.

Many people who feel pride about Emma Sansom discuss “division” about the statue like it is a new phenomenon. The outcry against the statue is the voice of an awakened community. They understand that it is time to address the focal points of what has really caused a division in our community for over a hundred years. It only seems like a new “division” to those of us who benefit the most from the “normal” status quo.

We ask those who may feel a sense of pride about the statue to examine if most of their Black neighbors feel the same pride. You may say you are not personally racist and have good deeds to prove it. The statue’s effect in Gadsden is not about anyone’s personal feelings or failings – it is a feature of the systemic oppression that acts to this day against the freedom of Black people.

Gadsden’s population today is more than one-third Black people. What are we doing with a monument that celebrates an achievement meant to keep a third of our neighbors in bondage?

Think beyond your personal experience and towards the whole of the Gadsden community. Can we fulfill our potential as a beloved community if more than one-third of our neighbors are daily reminded that the town celebrates a time when their relatives were enslaved? Removing the statue will take a weight off our backs that we may have never recognized.

The debate that considers these statues as “history” today speaks to the success of the Lost Cause’s cultural hegemony. Yes, we must remember – a history never to repeat. Gadsden does not have to celebrate a man who led the perpetrators of racist terror. We can leave the Lost Cause behind, beginning by removing its symbols that haunt us.

Look to the heartening installation of a memorial four years ago to the memory of Black Gadsdenite Bunk Richardson. In Feburary 1906, Richardson was framed for the rape and murder of a white woman, taken from the Etowah County jail and lynched by a mob of 25 masked men.

This act of racist injustice happened the same year the UDC commissioned the statue of Sansom and Forrest on Broad Street. Identifying and commemorating the victims of injustice is a necessary part of making justice possible, and we can all do it together. Those are the kinds of memorials we need in Gadsden.

We can remove this statue just like other Alabama cities are doing. This month, the mayors of Birmingham and Mobile authorized and executed the removal of Lost Cause statues. The University of Alabama Board of Trustees and the Madison County Commission voted to remove Confederate memorials in recent weeks. The Gadsden community’s task is neither impossible, nor a logistical challenge. It is time to make the moral choice – no more Lost Cause in Gadsden.

What does it look like to tell the story of Gadsden that points us towards justice and away from racialized domination? If the statue of Sansom and Forrest remains standing somewhere when removed from public view, it needs context showing that it celebrates the cause of human enslavement – and that today we want to build a society of liberation for all people.

If we are silent, we are complicit in the ongoing injustice against Black people. As Emma Sansom’s nieces and nephews, the best first step we can take to abolish the stain of white supremacy in Gadsden is to remove this symbol of the enslaving power that once ruled this land. We can eliminate the source of division and fulfill the American promise of a democracy full of equal participants.

We are encouraged by the multiracial makeup of both the BLM protesters and the City Council members calling for the statue of Sansom and Forrest to be moved. The movement calling to take the statue down has already made progress in eliminating racial division by standing together. We stand with them. The promise of a democratic society, where all are created equal, lies after the statue’s shadow over Broad Street has faded. Remove the statue, and let’s get to work on building a beloved community in Gadsden and in the United States.

Signed,

- Donald Rhea

- William Henry Rhea III

- Marie Rhea Singleton

- Richard Rhea

- Kelvin Knight

- Leigh Ann Rhea

- Nina Ellen Rhea

- Anna Rhea Knight Hopkins

- Karen Lynn Knight Craft

- Preston Rhea

- Holly Rhea Hanks

- Laney Rhea Eskridge

- William Henry Rhea IV