Alabama saw yet another record-high daily increase in COVID-19 cases on Thursday, and although a commercial contract tracing firm is to soon start working in the state, with cases so widespread and many not tied to specific events or places, the state health officer worries it’s too late for tracing to be effective.

Alabama recorded 1,129 new COVID-19 cases on Thursday. The previous high was June 14 when the state added 1,014 new cases. The state’s 14-day rolling average of new cases was also at a record high Thursday at 734.

{{CODE1}}

There have been 32,753 confirmed COVID-19 cases and 880 deaths in Alabama since the pandemic began. Over the last week, Jefferson County recorded nearly 13 percent of the state’s new coronavirus cases. Multiple counties across the state continue to see increasing cases and are hitting record highs regularly.

On Tuesday, state hospitals were treating 680 coronavirus patients, the third highest daily patient count since the pandemic began. The seven-day rolling average of COVID-19 patients on Tuesday was at 659, the highest it’s been since the beginning of the health crisis.

The number of hospitalized COVID-19 patients on Wednesday, the latest data available, statewide was 667.

{{CODE2}}

Alabama State Health Officer Dr. Scott Harris, in an interview with APR Thursday, said that while the number of new cases and the number of tests performed continue to rise, so do the percent of tests that are positive. That means it’s not just more testing that’s finding new cases, and there’s continued community spread.

The 7-day rolling average of the number of tests performed in Alabama increased by 7 percent in the last two weeks, but the 7-day rolling average of percent of tests that were positive increased by nearly 30 percent in that time.

Harris said while there is some variation in the percent positivity number due to commercial labs sometimes saving and sending negative results in batches “but you can see the trend is that it’s definitely not going down.”

{{CODE3}}

Harris said he’s concerned about continued community spread of coronavirus, and said that while in the past many cases could be traced to specific events or locations — a nursing home or a gathering — that’s no longer the trend.

“We’re still seeing a significant number of cases that aren’t linked to another case, as far as we know,” Harris said.

Dr. Jodie Dionne-Odom, an infectious disease expert at UAB, told APR on Wednesday that contact tracing is one of the oldest and best tools to slow and prevent the spread of a virus. It works by identifying a case, then contacting everyone the person may have infected, then encouraging them to quarantine and prevent giving the virus to others.

“We do it for tuberculosis. We do it for types of diarrheal illnesses. We do it for all different types of outbreaks where we’re trying to understand the extent of spread and really figure out how much of our community is involved,” Dionne-Odom said.

But what makes COVID-19 so challenging is the virus’s contagiousness, and because people can infect others with the virus before they begin to show symptoms and sometimes if they have no symptoms at all, she said.

Imagine a person going about their daily routine, going to a grocery store, a meeting or visiting family and friends, she said.

“The numbers of people that they could have exposed to, even if they were diagnosed quickly, within a three or four-day period, could be dozens and dozens and dozens,” Dionne-Odom said.

And with so many new cases popping up in counties across Alabama, that makes contact tracing all the more difficult, she said.

The number fluctuates as the department pulls people from their regular jobs to conduct contact tracing when needed, but Harris said Alabama Department of Public Health, at any given time, may have around 150 people doing the work. That’s up from 120 earlier this year.

A plan discussed by state officials in May to have school nurses train and conduct contact tracing never materialized. Harris said there were a myriad of difficulties with the plan, from the availability of the school nurses to do the work, to getting them trained and started in time before school is to restart.

“We thought it was a good idea, and they were helpful and tried to work it out, but we just never were able to work it out,” Harris said.

ADPH has a contract in place with UAB and beginning next week medically-trained phone bank operators there will begin conducting contact-tracing for the state, Harris said.

A contract is still being negotiated with a professional contract tracing firm, Harris said, but he expects the company, which does the work in multiple states, to begin working in Alabama in July. He declined to name the company until the contract has been finalized. Federal coronavirus relief money allocated to ADPH will pay for the work, he said.

“Ideally, because this is a big national company, they will be able to trace all we can trace,” Harris said.

The problem isn’t so much the manpower to do the work, Harris said, but it’s getting Alabamians to answer an unknown number, then answer questions about who they’ve been around and how they’re feeling.

“I saw this week in New York City they added about 5,000 tracers, and they’re getting less than a 30 percent response,” Harris said. He wasn’t certain of the percent of people in Alabama who respond when contacted by a tracer, but said he’d estimate that it’s more than 30 percent but not substantially.

But beyond the problem of getting people to respond to a private matter with someone who says they work for the state government, there’s the matter of so many cases not connected to any specific place or event.

“I think the question that all states are asking now is, if you have a really widespread pandemic, you know, does contact tracing even make sense?” Harris said.

Harris reiterated what Dionne-Odom said, that the state has long done contact tracing for smaller outbreaks of diseases like syphilis or for tuberculosis

“Generally speaking, you’re talking about small numbers of cases and small numbers of contacts, right, and so that does make sense,” Harris said. “But with COVID, with these kinds of numbers, I don’t know that contact tracing is going to make sense in the long run, but we’re obviously doing our best because frankly, that’s the only tool we have right now.”

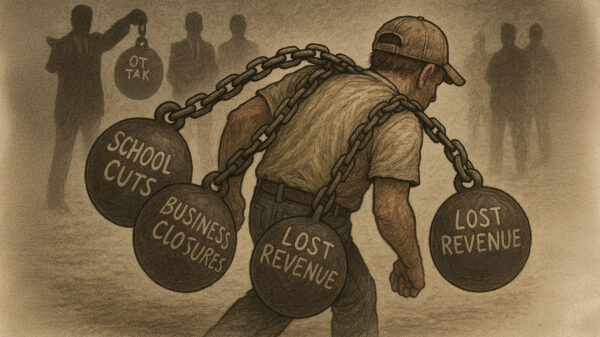

Asked if there’s been discussion of another round of closures due to the continued rise in cases and hospitalizations, Harris said while he can’t speak for Gov. Kay Ivey, who ultimately makes those decisions, “we certainly give her all the policy options that we can come up with and try to weigh the pros and cons.”

“I think we have to be realistic that there’s just not much appetite in our state or in our country for things that are going to shut people up at home,” Harris said.

Harris said that he believes Alabamians were cooperative when Ivey issued her first shelter-in-place order.

“I also think that absolutely slowed disease transmission and saved people’s lives,” Harris said. “I think that was successful. Yes, but clearly there’s an economic toll that has resulted around the world from doing that.”

Harris said, at this point, ADPH is going to try to give the best information possible to local officials “and then they can do what they want with that information. Hopefully they’ll make good decisions.”

Beyond local officials, Harris said it’s up to us all to make good decisions to slow the spread, and that comes down to wearing masks while in public and continuing to practice social distancing.

“It’s got to be a true behavior change,” Harris said.