Two participation trophies fell in Alabama on Monday night.

No tears were shed.

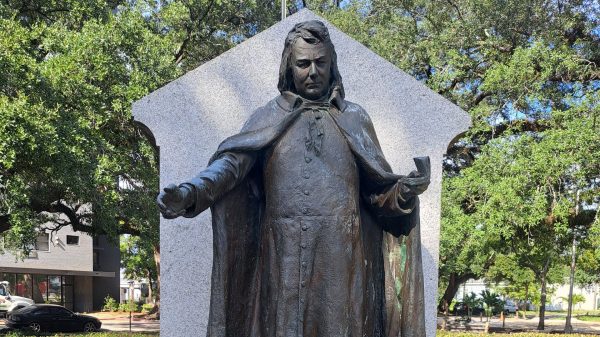

On the same day that the state “celebrated” Confederate Memorial Day — which is somehow still a state holiday some 150 years after the traitorous South surrendered in its quest to make legal the ownership of other human beings — a large monument in Birmingham’s Linn Park went away piece by piece and a metal statue of Robert E. Lee was toppled and hauled away from its spot outside of a Montgomery high school.

This is progress, I guess. At least those eyesores are gone (for now, in the case of the Lee statue), even if the attitudes that kept them in place remain.

It is no secret by now that I have never understood the fervor with which so many people in this state cling so tightly to reminders of defeated traitors who fought to enslave black people.

I mean, I understand why racists cling to them. I don’t understand how those who claim to “not have a racist bone in my body” also cling to them. I don’t understand our state lawmakers creating laws to protect them.

Monuments are meant to honor the people depicted in them. You don’t see us creating monuments of the 9/11 hijackers at the former World Trade Center site, do you?

You know why? Because while that day was historic and we’ll want to remember those who died forever, we don’t honor those who caused that devastation.

But then, I don’t actually think anyone is confused by this. The cries of “protecting history” or “not erasing history” are nothing more than phony excuses meant to mask the true intent of cowards too ashamed or too scared to say what they really mean.

And what they really mean is that they still cling to this notion of white supremacy. They’re just too scared of the societal backlash to put on a white hood and attend the meetings.

These people see the removal of the Confederate monuments as a loss — a personal loss. Because that tie to the confederacy and the sad, pathetic belief that they were somehow superior because of the color of their skin has sustained them throughout their lives.

That’s why they cling so tightly to these relics of the past — because those relics represent their “heritage” and their worth.

It doesn’t matter at all that poor whites and poor blacks have so much more in common in 2020 than poor whites and rich whites. If the two groups ever bonded, ever formed a mutually beneficial coalition, they could — by the power of their numbers — change America overnight to a more just, more equitable country.

But they won’t, because poor white people would lose their ability to look down on someone. And really, what good is life if you can’t make certain that someone out there has it worse than you?

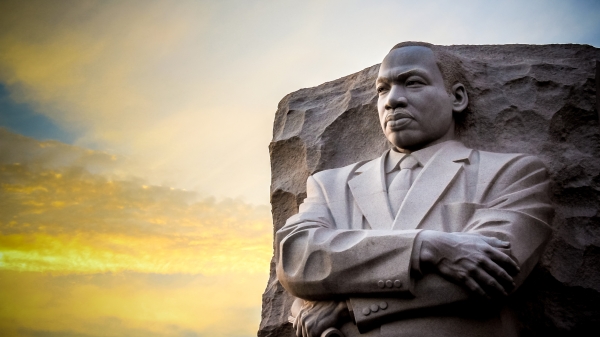

And so, here we are, more than 150 years after the end of the Civil War and more than 60 years since Dr. King crossed the bridge in Selma, still fighting battles over race and discrimination and hatred and intolerance.

Maybe the protests of George Floyd’s killing will finally be the straw to break this thing. Maybe the days of everything being on fire, along with those awful images of Floyd, will instill in the minds of enough people that there really are problems.

Maybe we can finally stop holding onto these relics of the past and concern ourselves more with holding onto each other.