The U.S. Department of Justice isn’t using its vast powers to ensure the country’s most vulnerable people can exercise their right to vote, but is instead focusing its efforts on defending laws that clearly violate the spirit of the Voting Rights Act, an attorney for the Southern Poverty Law Center said Tuesday.

The comments, from SPLC senior staff attorney Caren Short, came in response to a DOJ filing in a federal lawsuit filed on behalf of several plaintiffs by SPLC, The NAACP Legal Defense Fund and Alabama Disabilities Advocacy Program. That lawsuit seeks to implement curbside voting for at-risk citizens during the current pandemic and also to remove requirements for certain voter IDs and that witnesses sign absentee ballot requests.

The DOJ filed a brief on Tuesday stating that it is the agency’s position that Alabama’s law requiring witnesses for absentee ballots does not violate Section 201 of the Voting Rights Act, because it is not a test or device as referenced in the Act.

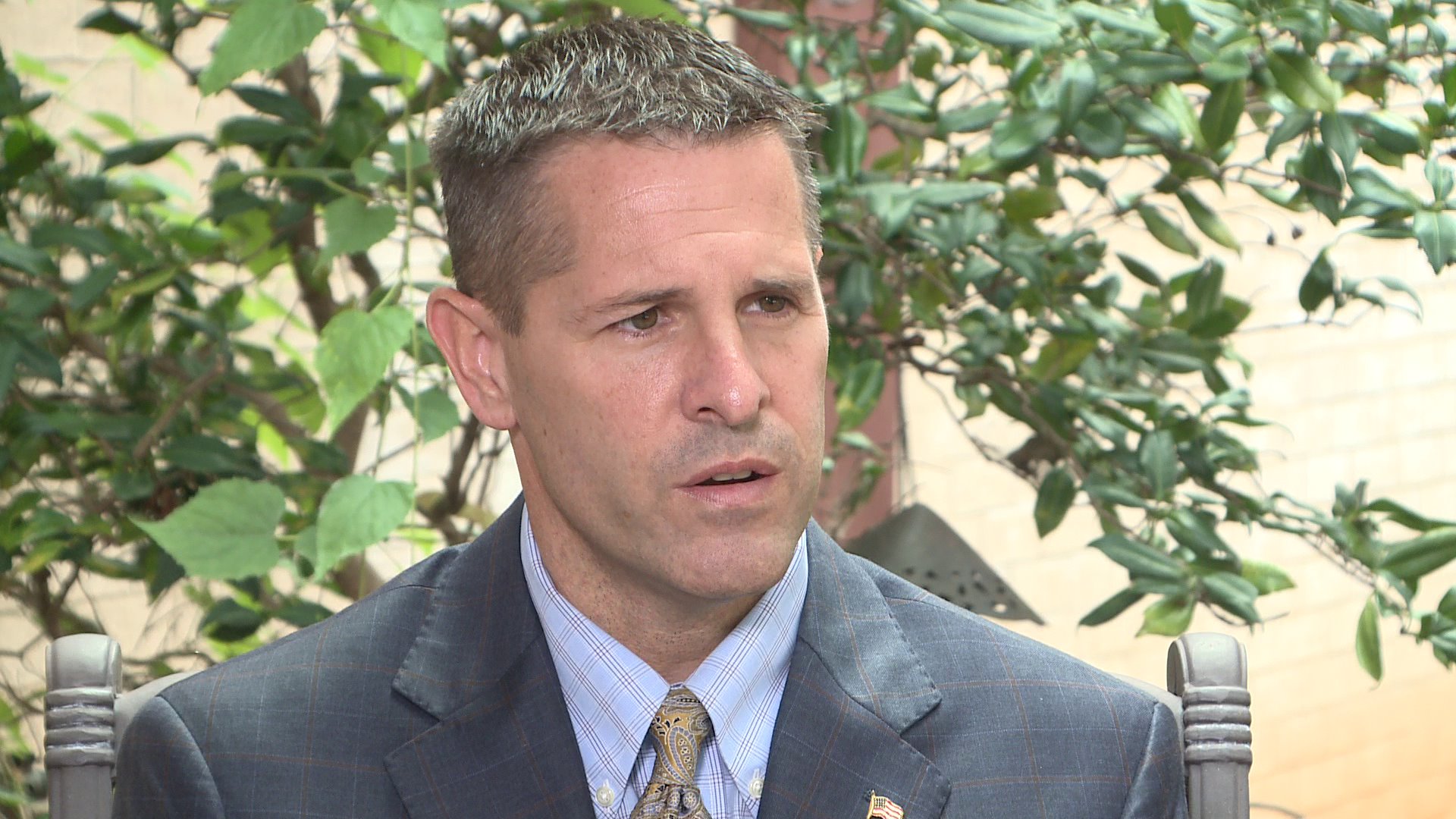

“It is not a literacy test, it is not an educational requirement, and it is not a moral character requirement,” Jay Town, U.S. Attorney for the Northern District of Alabama, said in the brief. “Nor, contrary to Plaintiffs’ position, is it a voucher requirement prohibited by Section 201’s fourth and final provision.”

Plaintiffs in the case have argued that the requirement for a single person with a pre-existing condition could pose a grave risk and reasonably lead to them being unable to safely cast a vote. In fact, they point out in the lawsuit instances in which the DOJ, prior to the Trump administration, also had argued against states requiring witnesses.

“Our complaint demonstrates how Alabama’s witness requirement violates Section 201 of the Voting Rights Act,” said Deuel Ross, senior counsel for the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund. “In the past, the DOJ itself has objected to witness requirements, but since February 2017, it has brought zero new voting rights cases.”

The “voucher” requirement was one of many tactics utilized by whites to prevent black citizens from voting. In practice, it required that any black person wishing to vote must first obtain the signature of a white person.

Towns argued in the brief that there were differences between voucher requirements and the witness signatures, including that the witness doesn’t have to be a registered voter and the witness is merely signing that he or she witnessed the absentee voter filling out the ballot.