Monica S. Aswani, DrPH, is an assistant professor of health services administration and Ellen Eaton, M.D., is an assistant professor of infectious diseases.

Editor’s note: The opinions expressed in this perspective are those of the authors.

As states re-open for business, many governors cite the devastating impact of physical distancing policies on local and state economies. Concerns have reached a fever pitch. Many Americans believe the risk of restrictive policies limiting business and social events outweighs the benefit of containing the spread of COVID-19.

But the proposed solution to bolster the economy — re-opening businesses, restaurants and even athletic events — does not address the source of the problem.

A closer look at the origins of our economic distress reminds us that it is COVID-19, not shelter-in-place policy, that is the real culprit. And until we have real solutions to this devastating illness, the threat of economic fallout persists.

Hastily transitioning from stay-at-home to safer-at-home policy is akin to throwing away your umbrella because you are not getting wet.

The novelty of this virus means there are limited strategies to prevent or treat it. Since humans have no immunity to it, and to date, there are no approved vaccines and only limited treatments, we need to leverage the one major tool at our disposal currently: public health practices including physical distancing, hand-washing and masks.

As early hot spots like New York experienced alarming death tolls, states in the Midwest and South benefited from their lessons learned.

Indeed, following aggressive mandates around physical distancing, the number of cases and hospitalizations observed across the U.S. were initially lower than projected. Similarly, the use of masks has been associated with a reduction in cases globally.

As the death toll surpasses 100,000, the U.S. is reeling from COVID-19 morbidity and mortality. In addition, the U.S. has turned its attention to “hot spots” in Southern states that have an older, sicker and poorer population. And to date, minority and impoverished patients bear the brunt of COVID-19 in the South.

Following the first COVID-19 case in Alabama on March 13, the state has experienced 14,730 confirmed cases, 1,629 hospitalizations and 562 deaths, according to health department data as of Monday afternoon.

{{CODE1}}

Rural areas face an impossible task as many lack a robust health care infrastructure to contend with outbreaks, especially in the wake of recent hospital closures. And severe weather events like tornadoes threaten to divert scarce resources to competing emergencies.

Because public health interventions are the only effective way to limit the spread of COVID-19, all but essential businesses were shuttered in many states. State governments are struggling to process the revenue shortfalls and record surge in unemployment claims that have resulted.

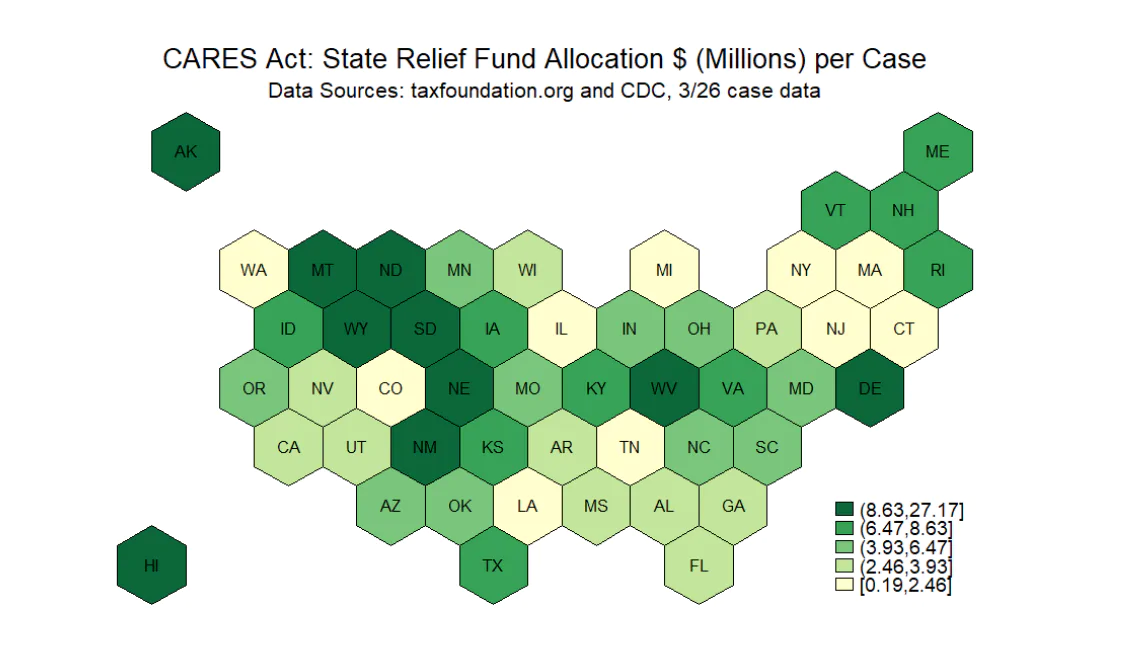

The Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security Act, or CARES Act, allocated $150 billion to state governments, with a minimum of $1.25 billion per state. Because the funds were distributed according to population size, 21 states with smaller populations received the minimum of $1.25 billion.

Although states with larger populations, such as Alabama and Louisiana, received higher appropriations in absolute terms, they received less in relative terms given their COVID-19 related medical and financial strain: the CARES Act appropriations do not align resources with state need.

As unemployment trust funds rapidly deplete, these states have a perverse incentive to reopen the economy.

Unemployment claimants who do not return to work due to COVID-19 fears, per the Alabama Department of Labor, can be disqualified from benefits, perpetuating the myth of welfare fraud to vilify those in need.

The United States Department of Labor also emphasized that unemployment fraud is a “top priority” in guidance to states recently.

Prematurely opening the economy before a sustained decline in transmission is likely to refuel the pandemic and, therefore, prolong the recession. Moreover, it compromises the health of those who rely most heavily on public benefits to safely stay home and flatten the curve.

Some would counter this is precisely why we should reopen — for the most vulnerable, who were disproportionately impacted by stay-at-home orders.

{{CODE2}}

The sad reality, however, is that long-standing barriers for vulnerable workers in access to health care, paid sick leave and social mobility pre-date this crisis and persist. And we know that many vulnerable Americans work on the frontlines of foodservice and health care support where the risk from COVID-19 is heightened.

A return to the status quo without addressing this systemic disadvantage will only perpetuate, rather than improve, these unjust social and economic conditions.

COVID-19 has exposed vulnerabilities in our state and nation, and re-opening businesses will not provide a simple solution to our complex economic problems.

No one would toss out their umbrella after several sunny days so why should America abandon public health measures now? After all, rain is unpredictable and inevitable just like the current COVID-19 crisis.

The threat of COVID-19 resurgence will persist until we have effective preventive and treatment options for this novel infectious disease.

So let’s not blame or, worse, discard the umbrella. Instead, peek out cautiously, survey the sky and start planning now to protect the vulnerable, who will be the first to get wet.