When Dr. Ken Duckworth learned that a reporter interviewing him was from Alabama, the first thing he thought of was college football.

“The absence of college football is not a mental health problem, but it takes away one of my favorite things in life,” said Duckworth, chief medical officer at the National Alliance on Mental Illness and a professor at Harvard University’s Medical School.

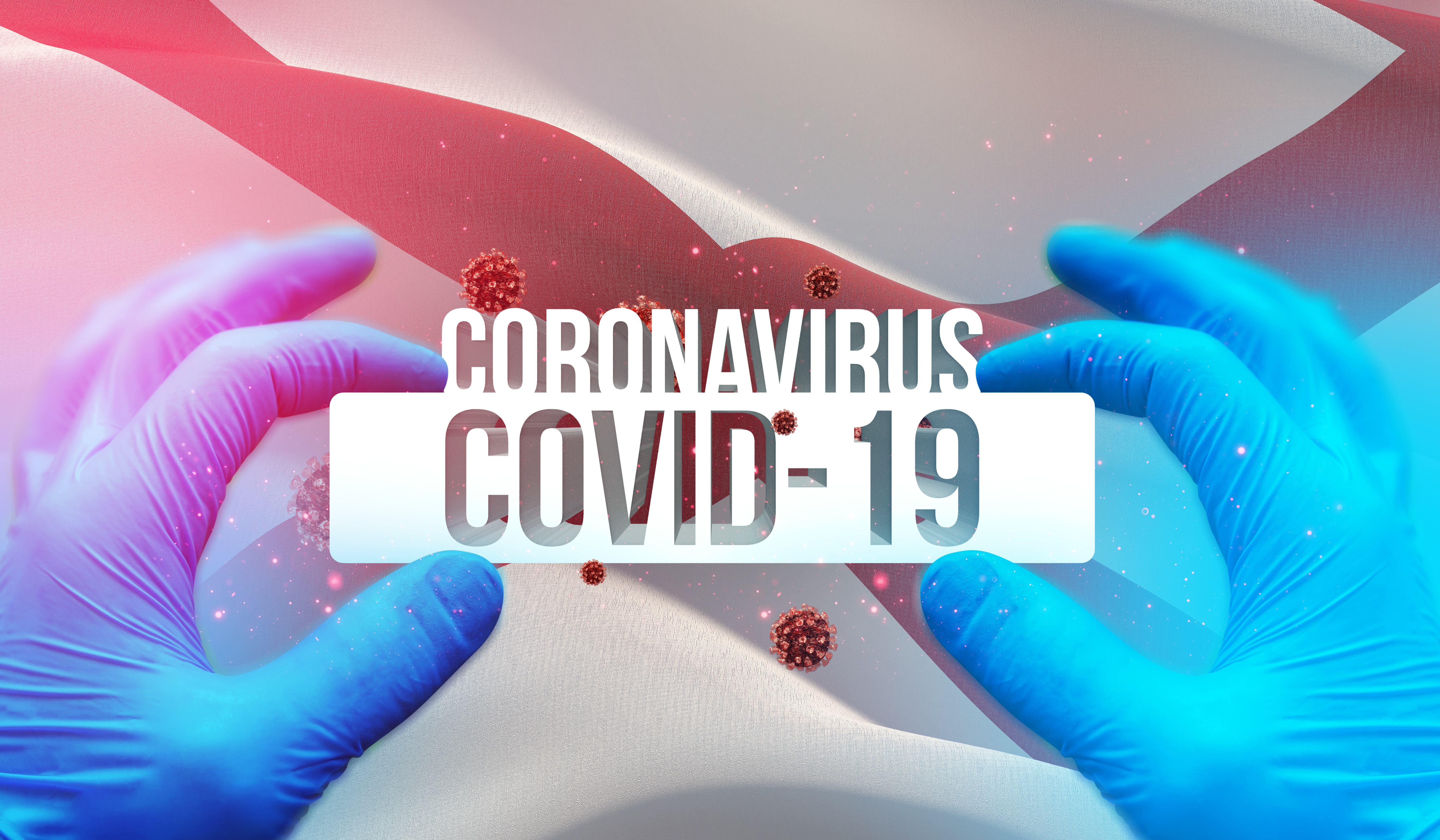

For many, the COVID-19 outbreak is impacting people through the loss of favorite rituals and events, and for young people, the loss of opportunity, Duckworth said.

There’s also concern that the nationwide mental health field, and the ability to test and conduct contact tracing, aren’t yet up to the task of a second or third round of COVID-19, Duckworth and medical experts said recently. The toll on mental and physical health from the virus has been great, and it isn’t over yet, he said.

Testing will have to improve if states are to control any future waves of COVID-19 as many reopen and residents begin to head back out into workplaces and social events, according to infectious disease experts who spoke during a live-streamed press briefing Tuesday, hosted by the Infectious Disease Society of America.

Since the first cases of COVID-19 infection were identified in the U.S. in January there have been about 1.5 million confirmed cases across the country and about 90,000 deaths, said Dr. Preeti Malani, Chief Health Officer at the University of Michigan, professor of medicine of Infectious Diseases at the university and an Infectious Diseases Society of America fellow.

“And of course we don’t know the actual numbers. They’re probably many folds higher because of challenges early on with testing and asymptomatic infection,” Malani said.

Malani said that everyone is worried about a second and potentially third wave, but that physicians also accept that coronavirus is something we’re all going to have to live alongside as we try to get back to some normalcy. It will be about trying to control outbreaks and the most vulnerable among us, she said, especially those in prisons and jails, nursing homes and who work in close contact with others, such as meat-packing plants.

“My hope is that we can try to share responsibility in this situation, where my behavior affects everyone else around me,” Malani said.

The issue will come down to testing, she said, so that cases don’t go undiagnosed and allow a person to spread the deadly virus widely.

Dr. Leonard Mermel, professor of medicine at Brown University, director of the Department of Epidemiology and Infection Control at Rhode Island Hospital and another Infectious Diseases Society of America fellow, said during the briefing that health experts are learning by looking at cities that tried to open too quickly without the capacity to control future outbreaks.

“We have to be particularly careful about our highest-risk individuals,” Mermel said. “I would also add homeless individuals into that population.”

Mermel also said that the public health infrastructure at the state and federal level “has been pretty much decimated over the last several decades in our country.”

The country needs to ensure state and local health departments have the resources necessary to do the testing and contact tracing to track those who’ve been exposed “to try to contain things quickly before it gets out of hand.”

In Alabama, the number of new COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations and deaths continue to rise, and state public health officials are working to hire many more contact tracers. Testing, while it has increased in recent weeks, still isn’t as broad statewide as medical experts believe is needed to fully see the problem and prevent the virus’s spread.

For many, the uncertainty of what may happen, of the probable loss of something due to coronavirus, can impact a person’s mental health, Duckworth said.

“Goals, proms, friendships, and of course the remote possibility that you might lose somebody you love, which is also a real risk,” he said.

One in five Americans had a mental health diagnosis before the COVID-19 pandemic, Duckworth said, and the U.S. was already in a suicide and drug overdose death crisis before the first coronavirus case in the country was confirmed.

Mental health professionals are now working nearly entirely via telemedicine, where they meet with patients via videoconference on laptops and phones, Duckworth said. He doesn’t know a single provider who’s met with a patient in person in their office since the crisis began.

“Mental health is not a quick-moving team, and they know that there’s gonna be trauma effects, first responder effects, health care worker trauma,” Duckworth said. “This is not a quick hit. The challenge is, of course, that as demand continues to increase, how do we help with supply?”

Duckworth said the mental health field hasn’t yet done enough to grow the supply of providers to meet the needs during this unprecedented health crisis.

But one thing is clear, he said. The switch to teletherapy has been quick and broad.

“Everybody is getting experience in tele-treatment, teletherapy and telepsychiatry and almost everybody likes it. Patients show up on time. They don’t have to drive. They don’t have to pay for parking. It’s interesting,” Duckworth said.

With the growth of telemedicine during the coronavirus pandemic comes the concern, however, that for many lower-income people, especially in rural areas, there’s not the same access to the Internet, laptops and smartphone technology needed to get the care. Even flips phones can work in some cases, Duckworth said, but there are other unknowns.

Will mental health care provided through things like flip phones continue to be covered by insurance providers and employers as the health crisis continues to impact the economy?

“The question is, will the universities and other big employers want to foot the bill to make it easier for people who have commercial insurance to get that kind of access?” he said. “And that’s a question that is an unknown, because those businesses are going to be facing new pressures.”

Duckworth also had advice for people who may be experiencing the stress and anxiety of living through such a difficult time.

“First of all, take care of your own self. Not everybody needs a therapist,” Duckworth said. Get exercise, don’t use substances to excess, and put down all media after dinner, he said.

“Talk to people. Stay connected. Don’t be a loner. Connect with cousins. Zoom calls with nieces and nephews. Really work the family, friendship angle. Really work it,” Duckworth said.

But for those who may be having trouble functioning, or who are having active thoughts about harming oneself, Duckworth said they should reach out to medical professionals or help.

“We are all in this together,” he said. “It’s giant test of resilience, and we weren’t ready for this pandemic. I don’t think that’s very controversial. In terms of our response and psychologically. People hadn’t been stressed in this way.”

The two infectious disease experts had advice for the public as states continue to reopen more segments of public life and commerce.

“Ramping down was pretty easy,” Malani said. “Although it didn’t feel like it at the time, we basically flipped the switch. Reopening is going to be much more complicated.”

Employers should make certain workers aren’t coming in sick, she said, cleaning protocols should be strengthened and there should be strong guidelines for the wearing of personal protective equipment such as masks and gloves.

“Memorial weekend is coming up and a lot of us want to plant flowers in our garden. If you drive up to the nursery and you see that there are hundreds of cars in the parking lot, it might not be a safe time to shop,” Malani said

It’s important for the public to continue wearing masks when in the public, and to maintain social distancing by staying at least six feet away from others, Dr. Mermel said

Asked about states are reopening despite not having met the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s criterion for doing so, which include that new confirmed cases drop for at least 14 straight days, Malani said it’s been encouraging that we’ve not seen massive outbreaks but that “we’re a little early.”

“And in terms of seeing cases, I’m interested in hospitalizations and, of course, deaths,” Malani said. “And I think the jury’s still out. Hopefully, we’re doing this responsibly, but also if you’re not testing and tracking you might not see it.”