Alabama’s chief medical officer said Wednesday the Department of Public Health needs more resources and staff to be able to handle the current wave of COVID-19 and prepare for what could come next.

“I don’t know how long we’re going to be here, as far as in this role, but we’ve been told to expect a second wave. We’re not out of the first wave, yet,” said chief medical officer Dr. Mary McIntyre, one of the state’s top public health officials. “That in itself is scary, and we’ve got people unfortunately retiring. So we need to be able to replace them but also hire additional people to be able to continue to do this and the next thing that comes up.”

Supply chain disruptions, a lack of supplies needed for testing, not enough resources and limited staff are hampering the Alabama Department of Public Health’s ability to expand the testing and contact tracing efforts needed to bring COVID-19 under control, she said.

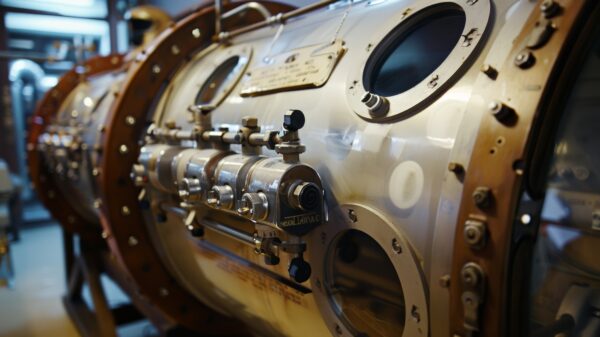

“Despite what you’ve all heard from the federal level, the ability to even now get the reagents that we need continues to be hit and miss,” she said. “We will have reagents within the state lab, and then there will be issues. We get an order, and we may get enough to test for a day and a half.”

The difficulty in obtaining reagents — the substances used to perform tests for COVID-19 in the state’s lab — has made it impossible for the state to consistently up its testing capacity even as the number of cases in the state continues to rise.

“We actually speed up the processes to be able to do them quickly, and then we have to drop back to a manual process in order to wait for the reagents to come in,” McIntyre said.

Over the last week, the state has reported more deaths from COVID-19 than at any point prior. Hospitalizations remain high and more new cases have been confirmed per day over the last week than during what was expected to be the peak in mid-April.

“The numbers continue to climb,” McIntyre said. “The numbers are not decreasing. Our numbers continue to go up.”

{{CODE1}}

Private commercial labs and clinical labs like UAB have been able to boost testing across the state, but they have faced the same shortages of needed supplies to varying degrees. Even with boosted testing capacity from private labs, the number of tests performed per day is still far below the levels recommended by the Harvard Global Health Institue, public health experts at UAB’s School of Public Health and others.

{{CODE2}}

Supply shortages of chemical reagents, personal protective equipment, viral transport media and swabs needed to collect samples and perform tests have been persistent since the pandemic arrived in Alabama in March. McIntyre said some shortages have improved, but reagents remain an issue.

“We can get the swabs. We can get the ice pack packs and the kits for people to be able to ship us this stuff,” McIntyre said. “What we can’t get and that we’re still running into issues with is the reagents.”

It’s been an issue not just for Alabama, but across the country, even as President Donald Trump has routinely claimed that the United States has the best track record for testing.

The federal government’s early response and lack thereof contributed to the slow rollout of testing in Alabama, where still less than 2.8 percent of the state’s population has been tested even as the number of tests performed has increased over the last few weeks.

“We couldn’t get swabs. It took us three weeks to get swabs within the state,” McIntyre said. “We called everybody. We were calling the federal government. We were calling on every vendor we could think of, but the vendors had been told not to sell to the states. And basically the federal government was pulling those swabs.”

The lack of support from the federal government and the persistent supply chain problems forced the state’s lab to develop its own reagents and viral transport media, the materials used to transport test samples from collection sites to labs, but that process took time, money and people that could have been working on other things.

“If you’ve looked at anything with the numbers with staffing, we over the years have gone down,” McIntyre said of cuts to the Department of Public Health’s staff and funding. “This has proved to be very challenging from the standpoint of being able to do what it is we do. The staff, our employees, when I say they have gone over and beyond. They worked 16-hour days or more. They worked seven days a week.”

Now the department faces an even more unprecedented challenge without having fully solved the issue of testing: hiring hundreds of contact tracers to help find, question and isolate positive cases to avoid more widespread transmission. As cases continue to rise, that means even more staff will be needed to isolate the cases.

“We do need several hundred more to assist with just trying to get to people and explain to them how to protect themselves,” McIntyre said of hiring more staff to perform contact tracing. “We really need to be doing contact tracing more, we’re doing it with the staff we have, but we’re not doing it as timely as we want to do it.”

Finding and isolating cases quickly is as important as doing it at all. Peak transmission can occur in the first few days of infection before a person realizes they have the virus or before they develop any symptoms if they ever do.

With adequate staff, the health department would be able to quickly identify positive cases, call them, find out who they’ve been in contact with, and warn those people to get a test and isolate before they unwittingly spread the virus further.

With limited staff, carrying out that process quickly enough to make a real impact has been difficult.

UAB’s Dr. Mike Saag, an expert in infectious diseases, said Wednesday that to perform effective contact tracing will first require an adequate level of testing, which he said the state has not reached yet.

“Then we can identify the people who have been in their local environment in the 24 hours especially before they got symptoms,” Saag said of the urgency of testing and contact tracing quickly. “Why? Because during that 24 hours is when the peak amount of transmission happens.”

Such a testing and contact tracing system is becoming even more important as the state shifts back into more normal economic activity with businesses and restaurants reopening and several school systems announcing plans for in-person graduation ceremonies.

“Someone can be totally asymptomatic and they feel great,” Saag said. “And they’ll sit, and they’ll be spewing a lot of virus into the environment.”

Without adequate testing, including testing of those without symptoms, Saag said the state is reopening too quickly.

“Without knowing who’s infected, we’re basically flying into this epidemic blind or worse,” Saag said, noting that a high proportion of cases never develop symptoms. “We’re flying into the fog blind. And we’re not going to be able to know where we are, or how we’re going to land the plane without information, and the best information we can get right now to see what’s going on is testing.”

For the past two months, testing has been limited to those who are hospitalized and those who are showing moderate to severe symptoms of the virus.

Just recently, the Department of Public Health began encouraging testing asymptomatic people in high-risk groups like nursing home residents and those with underlying health issues.