As the U.S. reels from an unprecedented global health emergency, many people have been sounding alarms about the magnified threat posed to people in prison. With the highest incarceration rates in the world, America’s overcrowded facilities are prime environments for a contagion like the novel coronavirus to spread.

Mandatory minimum sentencing laws have played a major role in creating this scenario. Designed to prevent lenient sentences for certain crimes, they removed judges’ ability to exercise discretion. Long criticized as forcing arbitrary and outsized punishments on citizens convicted of a wide array of crimes, many of them nonviolent, such laws have been rolled back in many states. Congress has bipartisan support for an overhaul of federal sentencing guidelines, but legislation has been stalled for several years.

Reforms have been passed by states in as piecemeal a fashion as the laws were instituted. Alabama, Georgia and North Carolina are among the states that critics say have been slow to embrace meaningful corrective action. Alabama’s and Georgia’s prison systems have consistently ranked among the 10 most overcrowded in the nation, among other problems blamed for extreme conditions in their facilities. In North Carolina, staffing shortages resulted in temporary closures of three state prisons last year.

North Carolina’s prison population more than doubled between 1980 and 2016, according to the state’s ACLU chapter. The inmate population is projected to exceed capacity by 2025. The scenario is similar in Alabama and Georgia.

All three states have been slow to implement the substantive criminal justice reforms that advocates say are needed to reverse mass incarceration and also keep communities safer. Critics point to the tremendous drain on tax revenue created by warehousing so many people, as well as the threat to society represented by prison conditions: a nonviolent offender is more than 80 percent more likely to commit a violent crime after serving time.

Yet the pandemic has thrust the situation, long in the making and difficult to dislodge from its codified entrenchments, to the forefront of the national conversation amid a chronically frenzied news cycle.

Caught between life and death in Alabama

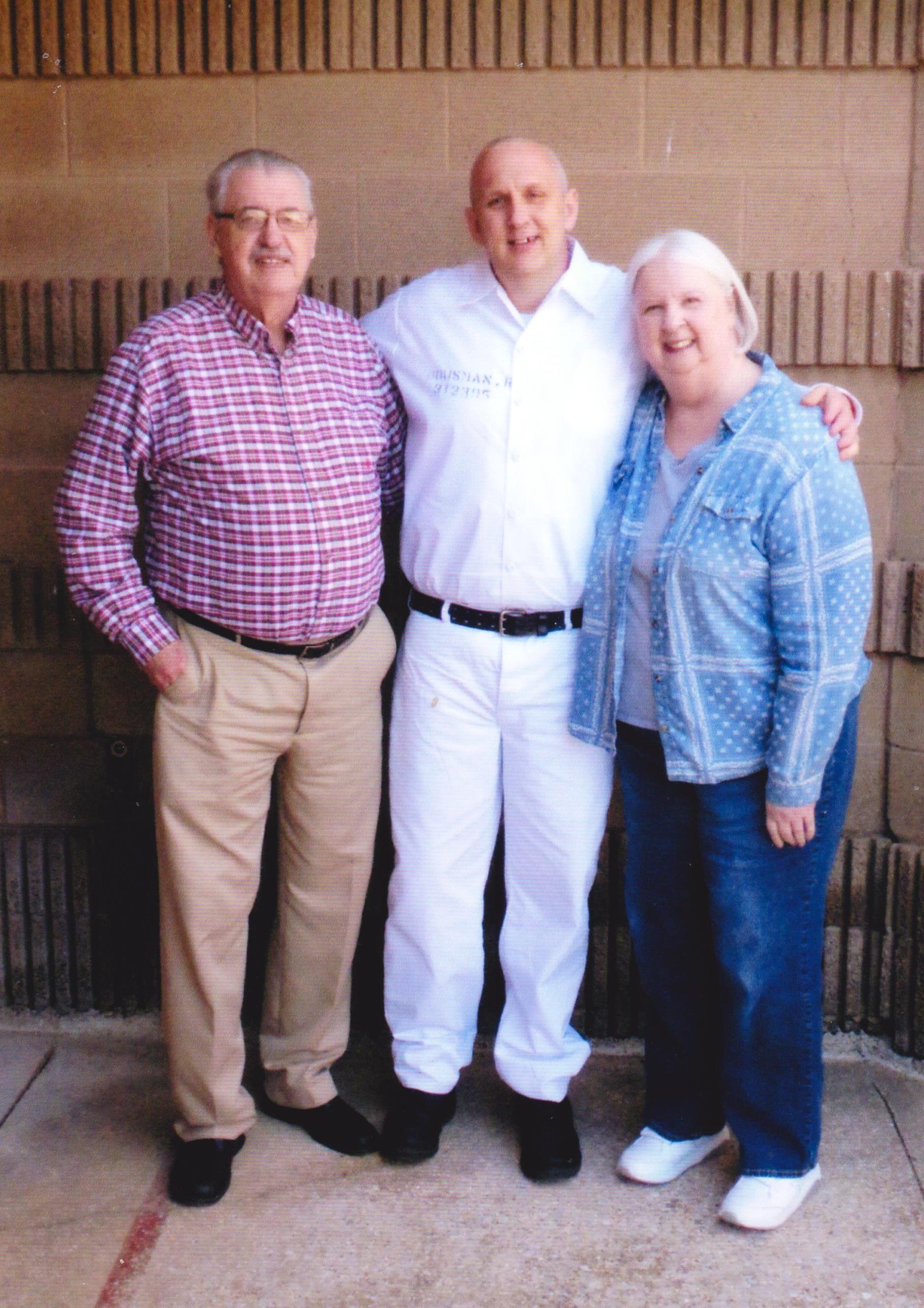

Sara Dodson hasn’t been sleeping well. Her son is imprisoned at Limestone Correctional Facility in Alabama, living in a crowded open dorm. The prison wasn’t designed to hold this many men. Guards have been handing out masks made from old inmate uniforms.

In Alabama and across the nation, state and federal prisons and jails struggle to control the spread of the virus that causes COVID-19. Since President Richard Nixon declared a “war on drugs,” harsh sentencing laws produced the highest incarceration rates in the world. Packed with people who can’t leave, these facilities harbor ideal conditions for the virus to spread.

Dodson’s son, Russell Housman, is serving a life sentence. He was convicted in 2019 as an accomplice in a robbery and sentenced under the state’s Habitual Felony Offender Act (HFOA), enacted by the state in 1977 to “deter repeat offenders and … to segregate that person from the rest of society for an extended period of time.”

To apply the law to Housman’s case, prosecutors cited a theft conviction he had from 1997, when he was 23. He and two fellow employees at a Marvin’s lumber yard used fraudulent return slips to steal $927.

Housman was the only one charged. He was convicted of second degree theft, a class C felony at the time. Housman was arrested again in 2001 and convicted of drug possession. He was convicted of the same crime 15 years later, in 2016. Both were class C felonies.

“No choice in the matter”

On Dec. 20, 2017, Housman was riding in a car with three other men in Huntsville. He got out of the car before the others drove to a Christmastime Santa village, where employees were preparing to leave with the day’s proceeds. The display was a fundraiser for a local children’s museum, according to court records.

One of the three men used a pellet gun to rob two women of about $4,000. One of the suspects sprayed pepper spray toward a security guard who was accompanying the women.

Housman had worked as a security guard at the venue and both women knew him. They told police that neither of the men who robbed them was Housman, court records show.

Housman claimed he was unaware the men planned to commit the robbery and had nothing to do with its planning. He said he walked for six hours after they dropped him off — until they picked him up again. A police officer stopped Housman during his walk and made a police report, court records show.

In 2016, the state legislature passed sentencing reforms in an attempt to address severe prison overcrowding and the federal government’s concern about violence in its facilities The three crimes Housman was convicted of were downgraded to class D felonies, which would not have been applicable to a life sentence under the HFOA. Lawmakers did not make that change retroactive, however, so prosecutors were able to use his old charges to send him to prison for life.

Danny Dodson attended his step-son’s sentencing hearing and said the judge told Housman “I’m going to give you a chance,” and started to discuss a sentence that would have been much shorter, but the district attorney spoke up and said the judge couldn’t do so as it was a habitual offender case.

Housman’s attorney, Erin Atkins, filed an appeal on Feb. 6 in which she cited the trial judge’s concern about the harshness of the sentence.

“In this case, the trial court acknowledged that it would have considered a split sentence or a 30-year sentence but that it had ‘no choice in the matter,’” Atkins wrote to the court. “The court asserted: ‘I don’t have a choice. I don’t have a single choice. I was actually going to give you an opportunity. I was going to give you 30 years.’”

“He realized it could be a life sentence,” his mother said, but he didn’t think he would receive such a harsh sentence for a crime he wasn’t present for.

Dodson said his stepson’s case reveals a blatant disparity in Alabama’s sentencing laws, where a person can still be subjected to punishment deemed too severe for the crime because they committed it before the law was reformed.

“You can’t say that a system of laws are fair when it treats one group of people differently from another group,” Dodson said. “That’s what you’re doing.”

The castaways

Beth Shelburne, an investigative reporter with the American Civil Liberties Union’s Campaign for Smart Justice, has spent several years researching and reporting on the HFOA and its impact.

“We think about these policies and these extreme sentences because all of those people are the most vulnerable during this pandemic,” Shelburne said. “For people who have life without parole, they don’t have any options, and the states have given themselves no options by imposing those sentences.”

She said she hopes the COVID-19 crisis will increase awareness about prison overcrowding and the mandatory sentencing laws that exacerbated the problem.

Of Alabama’s 21,154 inmates, 519 are serving life without parole under the HFOA, according to the Alabama Department of Corrections’ latest monthly report. The vast majority — about 490 — are serving life for convictions other than murder, Shelburne said, and approximately 300 have just one violent offense on their record.

The HFOA also increases the length of sentences for thousands more. As of January, there were 6,135 people serving sentences ranging from two years to life without parole due to the law. The largest segment of them, 19 percent, were serving 20-year sentences. Alabama prisons were assessed at that time to be at 170 percent capacity.

Prosecutors often use the threat of harsher sentencing to get a plea deal and prevent a case from going to trial.

“They don’t want to really engage in that conversation,” Shelburne said of prosecutors discussing their discretionary use of the HFOA. “And I think part of the reason is it’s a very effective tool for them to use.”

When it became clear that COVID-19 would particularly threaten inmates, Shelburne said the first people she thought of were who she calls “the castaways.” Sentenced in the 1980s, they are now in their 50s, 60s and 70s. They fill the state’s faith-based honor dorms, areas where inmates who have not had serious infractions while in prison live under strict behavioral rules. Many who live in them are serving lengthy sentences for violent crimes.

“They are no longer a threat,” Shelburne said. Some haven’t had a disciplinary infraction in 20 or 30 years, she said.

“They’ve never committed a violent act when they’ve been in prison, and they are at the highest risk of developing COVID and dying from it,” Shelburne said.

“The hell of it is, this would be probably the safest population to release,” Shelburne said.

Some states are working to free inmates who have medical conditions that make them vulnerable to the disease. Alabama isn’t one of them.

People in Alabama prisons can get a medical furlough, but they have to apply for it. ACLU of Alabama and other advocacy groups called on ADOC to be proactive and identify inmates who meet the requirements rather than leave it to individuals to navigate the system on their own. . As of January, only 12 inmates were on medical furlough throughout the state, according to ADOC.

Dave Thomas, a 66-year-old terminally ill inmate at St. Clair Correctional Facility in central Alabama died on April 16 after testing positive for COVID-19. Two other inmates in separate prisons also tested positive, as had six prison workers in six facilities. Just 57 inmates out of the state’s approximately 21,000 had been tested as of Friday, however.

Slow to reform, and scrambling against COVID-19

In Georgia, 157 cases have been reported among inmates and 74 among staff, the state’s Department of Corrections announced on April 19. One staff member and four inmates have died from the disease.

Christopher Lanham, an inmate at Johnson State Prison, fears for his life. On Friday, he had a fever of 102 degrees, according to local advocates who are in constant communication with prisoners.

Fever, chest pain and coughing are common symptoms of COVID-19, but a fever is also a symptom of Non-Hodgkin lymphoma, the type of cancer Lanham has. He suffers from an aggressive form of the disease that weakens the immune system. He is one of more than 13,000 people in Georgia’s prisons who suffer from chronic illnesses. Ten are terminally ill and have less than six months to live, according to prison records.

As of Friday, 28 people tested positive for COVID-19 at Johnson State Prison. A 67-year-old inmate with an underlying medical condition died on April 9 of complications from the disease.

Lanham had just started chemotherapy when he was arrested for a probation violation in fall 2018. He is serving a 10-year sentence for drug, theft and trespassing charges. He will be eligible for release on Jan. 19, 2021.

Simone Cherie, an advocate with REFORM Alliance, a nonprofit collective opposed to mass incarceration, said she spoke to Lanham on April 14. He was in isolation in his cell, but said he is still afraid of contracting COVID-19 from the food trays that circulate in the facility.

The Georgia Department of Corrections (GDC) said it has increased the availability of hygiene products and cleaning supplies. Lanham told Cherie he had not seen any special efforts to sanitize the prison.

GDC said they gave masks to staff and inmates, suspended visits, tours and volunteer work, waived medical co-payments for prisoners and are performing routine fever checks.

Recommended social distancing guidelines, however, are nearly impossible to follow in 34 facilities that house 55,000 prisoners.

Advocates and defense attorneys have asked the Georgia State Board of Pardons and Paroles to release inmates who are at high risk of complications from the disease.

According to the GDC’s March report, 3,600 of the state’s prison population is 60 years old or older. There are also 23 pregnant inmates across the state’s system, and 682 inmates are HIV-positive.

Georgia’s “truth in sentencing” laws, which set mandatory minimum sentences for a range of charges, are widely considered to be among the most severe in the nation.

The Board of Pardons and Paroles is reviewing cases and considering releasing nonviolent offenders who are within six months of completing their sentence. The deciding factor, according to Steve Hayes, spokesperson for the board, is whether a person’s release is “in the interest of public safety.” About 31 percent of inmates in Georgia are serving time for nonviolent offenses. It is unclear how many of those have release dates within the six-month window.

GDC has protocols in place to notify the board if an inmate meets the criteria for a medical reprieve release. The offender would be classified by the GDC as terminally ill and the case is sent to the board for consideration.

In addition to space constraints, prisons are subject to a host of other conditions that put them at higher risk for contagion. Those include mental health issues and a lack of information, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The average Georgia inmate has an 11th-grade education. Thirteen percent have diagnosed mental disorders. Cherie said that a lack of access to updated information on COVID-19 has created a sense of panic among prisoners.

“People are getting violent. They’re getting agitated,” she said. “No one knows whether or not they should be sitting at the same table with someone, standing in line waiting to eat. They just have no idea.”

Marissa McCall Dodson, policy director for the Southern Center for Human Rights, said the burden of responsibility for keeping communities safe during this public health crisis should not be left to the people in them. Government and local organizations need to step in and fulfill that role, Dodson said.

“The Department of Corrections at the very least should be implementing the guidelines as they come from CDC and other public health agencies and organizations,” she said. “This role of, like, how much people understand individually, what they can and can not do, is not as important as what kinds of policies and practices that are put in place uniformly around the state.”

The politics of mandatory minimums

Bryan Stevenson, attorney and founder of the Montgomery-based nonprofit Equal Justice Initiative, said it is important that people understand that mandatory sentencing laws and the large prison population in the U.S. “was a political development.”

Stevenson has spent his career representing death row inmates and people who have received harsh sentences under mandatory minimum laws. He also works to expose racial bias in the U.S. justice system. He was portrayed by Michael B. Jordan in the 2019 movie “Just Mercy,” which was adapted from Stevenson’s 2014 memoir, “Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption.”

“It was not a development that was shaped by unprecedented levels of criminality,” Stevenson said of laws like Alabama’s HFOA. “We just criminalized whole categories of things that had not been criminalized before.”

National leaders began crafting “tough on crime” policies at the federal level as the country was exploding with anti-Vietnam War protests and the Civil Rights movement was building, Stevenson explained.

Yet most crime policy is created at the state level. As the tough-on-crime model was promoted at the federal level, state leaders began competing with one another to be the toughest on crime, Stevenson said.

“I do think it’s worth noting that when mandatory minimum sentences started to be enacted by state legislatures, they were never described as laws directed at judges and discussed by judges, but effectively that’s what they were,” Stevenson said. “They were essentially saying we don’t trust judges. We want to substitute our sensibilities, which are political, for the sensibilities of judges, who actually have to work with the nuances of these cases.”

Before mandatory minimum laws, people might spend four or five years in prison for an offense that was relatively minor. Waves of laws billed as reform suddenly began sending people to prison for 10 or 15 years for those crimes, he said.

“It’s the confluence of that sentencing that has created so much mass incarceration,” Stevenson said.

In Alabama, prison overcrowding and understaffing have produced the most violent prisons in the country, according to an Equal Justice Initiative report that examined prison homicides relative to their populations.

A U.S. Department of Justice report in April 2019 detailed its lengthy investigation into the state’s prisons for men, which found that Alabama is potentially violating inmates’ Constitutional rights under the Eighth Amendment and its prohibition of cruel and unusual punishment. Drugs, corruption and sexual violence are rampant in understaffed state prisons, investigators found.

Alabama’s prison homicide rate is almost nine times the national average for state prisons, according to the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics.

In response, the ADOC and state legislators have spent more money to hire additional correctional officers and have conducted contraband raids, with questionable results. Even under the current lockdown, where visitors are prohibited and only essential workers can enter prisons, drugs remain ever-present, inmates have said.

Reform advocates had hoped that Alabama lawmakers would take on substantive sentencing reform efforts this legislative session and repeal the HFOA altogether, but legislators instead filed five bills that stop short of that.

If approved, the bills would increase transparency into the ADOC, bolster re-entry support for people released from prison and make retroactive some sentencing reforms for non-violent crimes, although it’s unclear what priority legislators will give these issues amid the COVID-19 crisis. The state Legislature is expected to return to work on April 28. The state constitution mandates that this year’s session must end by May 18.

Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey is moving forward with a build-lease plan for three new mega prisons, to be located in north, central and southern Alabama and replace a majority of the state’s existing facilities. The cost has been estimated at $900 million.

But costs mean more than state budget line items, Stevenson said.

“We just can’t afford to throw everybody in prison forever and have good schools and good healthcare,” he said. “Good roads. Good infrastructure. We can’t afford to do all of those things.”

Putting crimes in prison

Alabama’s criminal justice reforms in 2012 and 2015 included reducing penalties for some non-violent crimes, new guidelines meant to make sentencing consistent statewide and increased funding for the parole system.

Reform advocates say lawmakers haven’t gone far enough in a state with a system that has denied parole to nine out of every 10 people eligible for it since September, according to the Alabamians for Fair Justice Coalition, a collective of advocacy groups, advocates and formerly incarcerated people.

States like Louisiana, South Carolina and Texas have made more substantive changes in their mandatory minimum laws, Stevenson said.

“We just haven’t had that in Alabama, and as a result of it we continue to have one of the highest rates of incarceration in the nation. We have some of the most serious problems when it comes to conditions of confinement, and there are still heartbreaking stories of unfair sentencing,” Stevenson said. “Someone has to say enough is enough, that we ought to be a state that cares about rehabilitation as much as we care about accountability.”

Stevenson said much of the debate in Alabama is shaped by people who think they can put crimes in prison, “but we can’t put crimes in prison. We put people in prison, and people are not crimes.”

“Even when people commit crimes, there’s a distance between them and the crime they’ve committed, and if we’re not willing to acknowledge that and to talk about that — and sometimes that distance is great enough that the sentence should be lower than someone else who commits that same crime, and I just don’t hear much about that reality,” he said.

He added that there remains a disconnect between the people in Alabama who are engaged in this debate and the people who are serving time, their families and the poor communities often hit hardest by these laws, he said.

“They’re so disconnected from the source of the problem that their solutions tend to be non-responsive,” Stevenson said, adding that former Chief Justice Champs Lion, who headed Ivey’s criminal justice study group and suggested stronger changes to the state’s sentencing laws, had been close enough to the problem to see it more clearly.

“Unfortunately our legislators don’t actually always have that same vantage point, so I think it shows in some of the policies,” Stevenson said.

Still, he has hope that things will change in Alabama and other states that have been slow to act.

“A lot of it is rooted in this notion that what we’re doing is just not sustainable. We’ve seen this in the prison context. We can not continue to warehouse people and be indifferent to the violent abuse and misconduct that we have seen,” Stevenson said. “I just would rather begin the process of reform — of correction, of repair — before more lives are lost, before more damage is done, before more tragedy takes place.”

Outbreak in North Carolina

North Carolina’s habitual offender law has also ensured a higher rate of incarceration. Officials have started releasing inmates to stop the spread of COVID-19, bringing the state’s prison population down by almost a thousand from the 35,085 who were imprisoned as of Feb. 29. However, it may not have been on the prison officials’ own volition.

Andrew Rhodes has been incarcerated at Wilkes Correctional Center in North Wilkesboro, North Carolina since 2016. He was sentenced for drug charges under the state’s habitual offender law. Under the law, a person who has pled guilty or has been convicted of three felonies is considered a habitual felon and is subject to a sentence for a felony class that is four times higher than what they were convicted of, but no higher than a class C.

Rhodes’ drug charges are H and G felonies, with maximum sentences of less than four years. The habitual felon status upgraded his sentence to class C, with a maximum sentence of 19 years.

About 4,800 people are serving sentences under the law, according to a Feb. 29 report.

Rhodes is scheduled to be released on Feb. 7, 2022. His wife Christina is concerned that his stay at the minimum security prison could turn out to be a death sentence. Andrew was diagnosed with Hepatitis C in 2008 and has been denied treatment since he has been incarcerated, his wife said. She is one of eight plaintiffs who sued Gov. Roy Cooper and North Carolina Department of Public Safety Secretary Erik Hooks.

“I’m extremely stressed about what will happen to Andy in prison with the COVID-19 virus going around,” Christina wrote in her sworn statement. “I worry he might not make it home for reasons that could be avoided.”

She joined an April 8 petition filed by the North Carolina State Conference of the NAACP, Disability Rights North Carolina, American Civil Liberties Union of North Carolina Legal Foundation and four prisoners. They demand the release of high-risk prisoners and those scheduled for probation, parole or work release.

That same day, the North Carolina Department of Public Safety (NCDPS) said it had freed six pregnant or elderly female inmates. Five days later, the department announced that it had released 300 inmates and planned on releasing 500 more. The inmates who were selected for release are either at higher risk for severe complications of COVID-19 or were scheduled to be freed this year.

“All offenders under consideration must meet strict criteria and all legal requirements, such as victim notification in certain cases, before a transfer to the community is approved,” the department said. The 500 people currently under review include pregnant women, those on home leave or work release and older adults (women 50 years and older and men 65 and older).

Andrew Rhodes is 38. He’s not eligible

“He’s terrified,” Christina said.

As of Sunday, 274 inmates have tested positive for COVID-19, according to the NCDPS. On Wednesday, all 700 inmates at Neuse Correctional Institution in Goldsboro, North Carolina were tested for COVID-19 after a surge of 80 cases was identified among offenders, many who were asymptomatic.

“The outbreak at Neuse CI is no doubt a cause for concern but not for panic,” Commissioner of Prisons Todd Ishee said. “We have medical protocols in place to handle this, and frankly it is better to know upfront what we are facing so we can do what is necessary to stop the spread.”

Andrew Rhodes said that guards have handed out extra soap and hand sanitizer, put up informational posters and segregated dorms. Each dorm holds about 60 people and has one bathroom. Prisoners who work in the facility are still authorized to move between dorms, Christina said.

Andrew’s next custody review is scheduled for May 1. Prison officials are offering time credits to inmates for good behavior amid COVID-19, but he has received four disciplinary infractions in the past six months, including a drug charge on March 24.

“He knows he’s not perfect and has made mistakes, but he didn’t get a life sentence,” Christina Rhodes said.

Waiting for what’s to come

For Housman, the hardest part of prison is being away from his family, he said. His son was 11 when Housman was arrested for the robbery charge that resulted in a life sentence.

Housman has always been close with his mother and stepfather. He played basketball in high school and attended community college for a time afterward. He worked as a youth counselor at Space Camp in Huntsville for a few years, then worked security at a local bar.

He struggled with drugs for years, he said, but he’s thankful for his sobriety since he’s been in prison. He’s relying on his faith in God and on the support of his mother and stepfather, “who have been there,” he said. “And I’ve neglected that and took that for granted for a long time.”

“It’s hard every day,” he said. “There are days when you don’t want to get off the rack.”

Justin Faircloth is serving time at the same prison. On Wednesday, he received his latest chemotherapy treatment for stage-4 colon cancer. In February, ADOC turned him down for a medical furlough, he said.

Faircloth said on Saturday that despite ADOC’s statement the day before that “Inmates also currently have access to liquid antibacterial soap,” he has seen no such soap in his dorm, where 60 men share three toilets.

Some inmates were given cloth masks made by inmates at another prison, but he was out of the dorm for treatment when they were handed out. He didn’t get one, and was told on Friday that he’d have to wait until Monday, he said.

“We’re just sitting here waiting for whatever is going to happen to happen,” Faircloth said. “There’s nothing we can do about it.”

Chemotherapy has taxed his body so much that it’s hard for him to get out of his bunk in the morning.

“This isn’t a place for anybody that has an immunodeficiency,” he said.

His wife Amber said that if her husband gets COVID-19, “he wouldn’t even have a fighting chance.”

“It’s scary,” she said.“It’s just all so scary.”.