Tuesday, federal District Judge Kristi Dubose awarded ownership of the shipwreck of the Clotilda, one of the last known slave ships, to the Alabama Historical Commission (AHC). The decision means that the state will have final say over remains of the ship, which was found near an island on the Mobile River north of the City of Mobile last year.

On July 26, the AHC and the State Historic Preservation Office had filed an Admiralty Claim in the United States District Court as part of an ongoing and long-term protection and preservation plan for the Clotilda, the last-known slave ship in the United States.

The AHC is charged with protecting, preserving and interpreting Alabama’s historic places. This charge also includes abandoned shipwrecks, or the remains of those ships, and all underwater archeological artifacts embedded in or on lands belonging to the State of Alabama. This mandate is set forth in the Abandoned Shipwrecks Act and the Alabama Underwater Cultural Resources Act.

The court order gives the state the authority so that work on the site and further preservation efforts can continue and provides legal protection of the site from amateur scavenger hunters.

The Historical Commission explained that pursing the Admiralty Claim was an appropriate course of action and protocol for abandoned wrecks embedded in state waters.

“The careful considerations for the protection, preservation, and interpretation of the Clotilda have been entirely methodical and strategic,” said Lisa D. Jones, Executive Director of the Alabama Historical Commission when the motion was filed. “We are charged with ensuring this tremendously important archaeological find is preserved and protected for Africatown and our nation. It carries a story and an obligation to meet every opportunity to plan for its safeguarding. AHC is laying the groundwork for ongoing efforts to not only ensure the Clotilda’s immediate assessment, but to also establish pathways for its longevity.”

Last year was the 400th anniversary of slavery’s arrival in this country. The first ship of African slaves arrived in Jamestown, Virginia in 1619, a year before the Pilgrims made their arrival. English privateers had seized a Spanish ship hoping to find gold; but instead captured a ship carrying a human cargo. Lacking the legal status to pull into a Spanish Port and not enough food to cross the Atlantic they sailed up the James River to the new English colony where they traded the first African slaves in the colony for food, before sailing on to Jamestown where they sold more of their plunder to farmers needing labor on their new Virginia plantations. Thus began the American slave trade. By the early 19th century what to do with the growing number of African Americans in bondage was a growing concern,

The international slave trade was outlawed by Great Britain in 1807. The U.S. followed and Congress actually banned the importation of slaves in 1808 while Thomas Jefferson was the President, himself a slave owner. The belief was then that with no new influx of slaves the practice of slavery would slowly diminish in economic importance over the coming decades and individual family farms would take precedence moving forward as America moved westwards and deeper into the continent. This was eleven years before Alabama was even a state.

Cotton and its role in the industrialization of the textile business was something that the Tenth Congress had not planned for. Millions of acres of prime cotton growing land was unleashed as the new nation pushed westwards into West Georgia, Alabama, Tennessee, Mississippi, Arkansas, and Louisiana and displacing most of the Native Americans that lived there and then later annexed Florida and Texas. The invention of the railroad, the cotton gin, and the steam ship would make exporting cotton from those remote new territories to textile mills in Great Britain a commercial reality. The demand for slaves in the South was growing not decreasing as most in Congress in 1808 had thought.

As slave demand continued to climb, Unscrupulous ship owners began the process of smuggling slaves from Africa into the country even though it was against the law to do so. The Clotilda was one of the last of those outlaw slave ships.

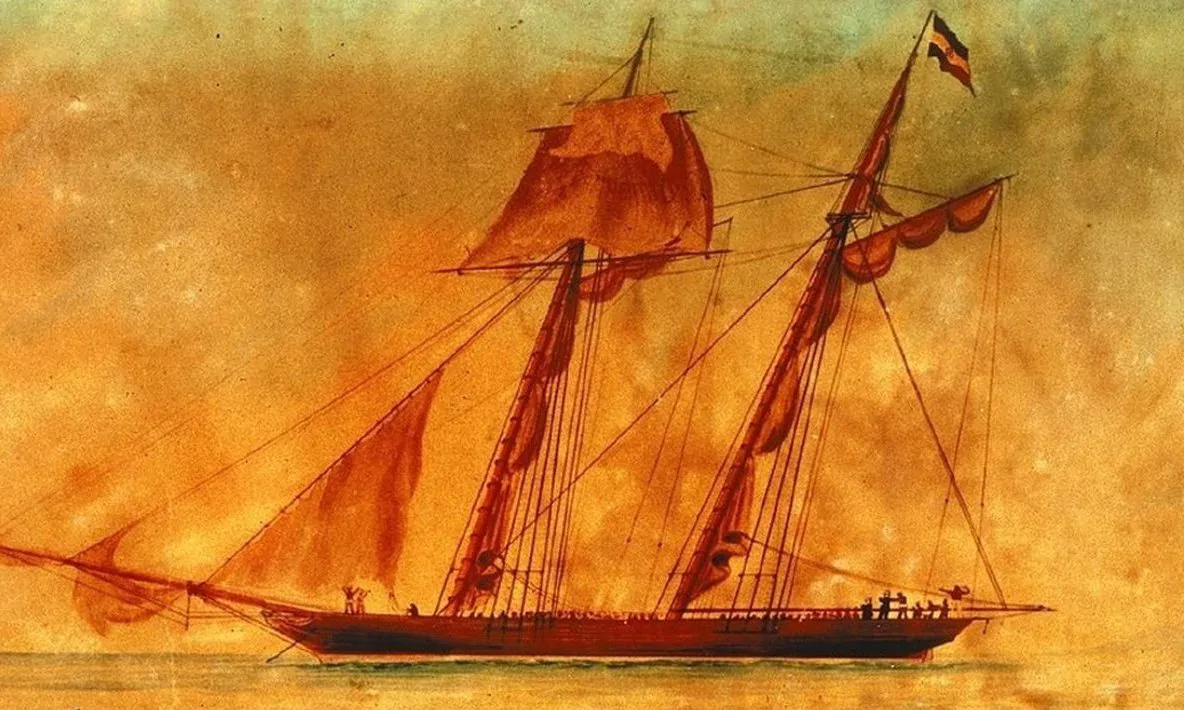

The Clotilda was a two-masted Gulf schooner. The mission was financed by wealthy businessman Timothy Meaher. The Clotilda, captained by William Foster, illegally transported 110 people from Benin, Africa to Mobile, Alabama in 1860, 52 years after that had become illegal in the United States.

What they were doing would be called human trafficking today and was very illegal even then. The co-conspirators attempted to evade authorities and destroy evidence of their criminal voyage by sinking, burning, and abandoning the vessel and then dividing the Africans among their captors, where they remained in slavery until the end of the Civil War.

A small band of the Clotilda passengers reunited post-war with the hopes of returning to Africa. When that dream was not realized, the survivors and their descendants established a new home for themselves in the Plateau area of Mobile – a community which is now known today as Africatown.

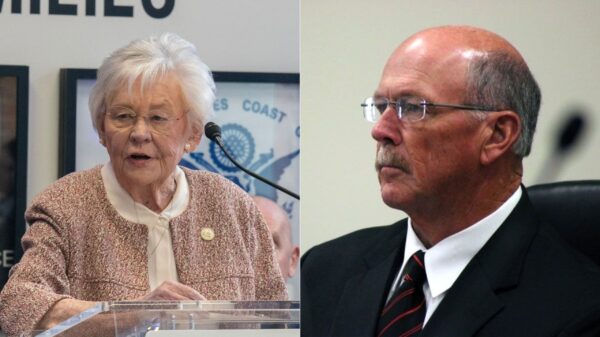

“By preserving the Clotilda, Alabama has the opportunity to preserve a piece of history. It is a prime example of an artifact that deserves our respect and remembrance,” said Governor Kay Ivey. “The Clotilda is very much a part of the story of the descendants and residents of Africatown, making it a significant part of the rich history of our entire state. Protecting this resource is imperative, and I look forward to Alabama taking on this important responsibility.”

The Clotilda was reportedly dynamited in the 1940s, which added additional complexities for assessing the ship’s integrity. Archaeological evidence supports these claims. In all, the ship is in a very fragile state, which has heightened precautions and the meticulous care for proceeding with all archaeological endeavors.

A few pieces of the ship have been removed from the river. These will be exhibited later this year in Africatown.

Original reporting by the Associated Press’s Jay Reeves contributed to this report.