On April 4, 1968, I was watching the little black and white television in our living room when the newscaster said that Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. had been assassinated. My tears flowed freely. Even though I was only 4, I knew that his death was a tragedy, especially for little black boys like me.

My parents and I lived on Chicago’s Southside in a yellow, three-story apartment building at the corner of 91st and Throop St. Three floors, three apartments, each one running the full length of the building with a huge picture window in the living room. Daylight streamed through ours as I watched the newscast through my tears, riveted by sorrow and fear.

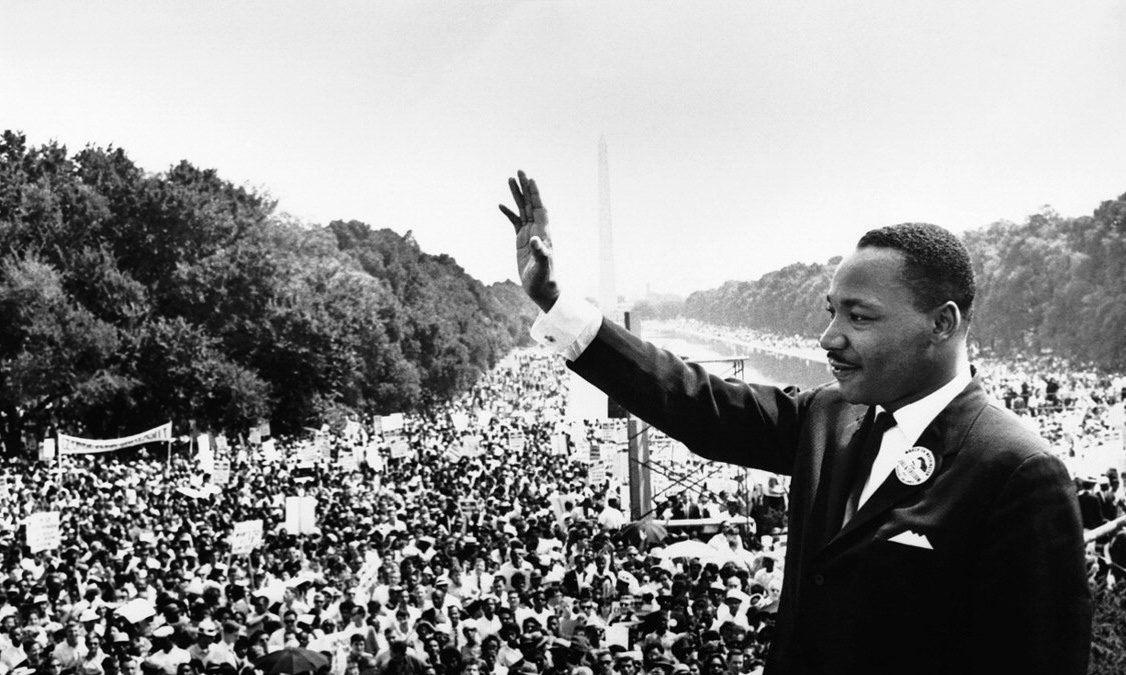

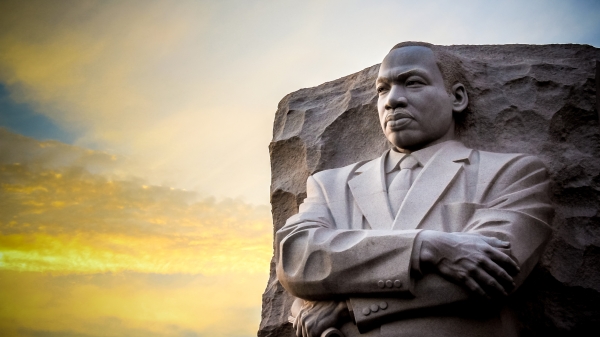

King was my hero, a man who courageously stood for justice and peace, even when threatened with violence. He was an eloquent preacher, whose soaring lines and velvet tones even captivated little children. And he was a father who, like my own, had tried to explain the nonsensical evil of racism to his child.

Yolanda, the oldest of the King children, had wanted to go to Fun Town, an amusement park in Atlanta. He had to explain to her that Fun Town was only open to white children. Chicago also had a Fun Town, but because it was in the black community – 95th and Stony Island Ave. – I don’t recall it being off-limits to me and other African-American children.

But the Chicago of the 1960s wasn’t that different from the Jim Crow South. Black families who tried to move into white neighborhoods were run out. The dividing lines were stark and clear. In fact, I only saw white Chicagoans while watching the news or when shopping downtown.

Northern segregation had a profoundly negative economic impact on black Chicago. It was so bad that three years before his assassination, King and his family actually moved to Chicago to apply his civil rights strategies to slums, low-wage jobs and overcrowded schools.

When he led a march through Marquette Park, a notoriously all-white enclave on the Southside, someone hit him in the back of the head with a rock. “I have seen many demonstrations in the South,” King said. “But I have never seen anything so hostile and so hateful as I’ve seen here today.”

King’s Chicago experiences undoubtedly shaped my reaction when I learned of his death. I know that because my father was a news junkie, politically aware, and what we used to call a “race man” – meaning that he identified as a black man more than as an American or even a Christian. He also was a card-carrying Republican, but of the Eisenhower type, not Goldwater or Nixon. So he and my mother admired Dr. King, and passed that admiration on to me.

And I retain it today, 52 years after his assassination. In fact, it’s grown stronger and deeper through the years.

My favorite King quote comes from his sermon “Loving Your Enemies,” preached at Dexter Ave. Baptist Church in 1957: “Within the best of us, there is some evil, and within the worst of us, there is some good. When we come to see this, we take a different attitude toward individuals. The person who hates you most has some good in him; even the nation that hates you most has some good in it; even the race that hates you most has some good in it. And when you come to the point that you look in the face of every man and see deep down within him what religion calls ‘the image of God,’ you begin to love him in spite of – no matter what he does, you see God’s image there.”

King was an expert in having enemies. He had more than his fair share, including whoever actually killed him. (The King family believes that convicted King assassin James Earl Ray was framed. Dr. William F. Pepper’s book “An Act of State” explains why.)

But what King undoubtedly knew, and what his killers failed to fathom, is that while prophets die, their dreams or prophecies live on. And true prophets always will be validated by history and time.

Which is why I expect Dr. King’s legacy to outlive all of us.