Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey is issuing a stay-at-home order, reversing course after two weeks of saying the state didn’t need one.

“I can’t say this any more clearly,” Ivey said. “COVID-19 is an imminent threat to our way of life. And you need to understand that we have passed urging people to stay at home. It is now the law.”

Before Friday, Ivey has said she did not believe the situation in Alabama warranted such a restrictive order.

“Late yesterday afternoon, it became obvious that more needs to be done,” Ivey said Friday at a press conference.

The governor said as recently as Thursday during a Twitter town hall that she wanted to balance public health and the economy, adding that the state is different from other states facing large outbreaks of the novel coronavirus.

“We have seen other states in the country doing that as well as other countries,” Ivey said last week. “However, y’all, we are not California. We are not New York. We are not even Louisiana.”

But by Friday morning — as cases of COVID-19 in Alabama surpassed 1,400 and the governors of all of Alabama’s neighboring states announced stay-at-home orders — Ivey decided to issue one, too.

“I am convinced that our previous efforts to limit social interaction and reduce the chances of spreading this virus have not been enough,” Ivey said. “And that’s why we are taking this more drastic step.”

The new rules will go into effect on Saturday, April 4, at 5 p.m. and will expire on Tuesday, April 30, 2020, at 5 p.m. (You can view the full order at the bottom of this page.)

Ivey said Friday that the state must take this “deadly seriously.”

“If you’re eager for a fall football season coming up, what we’re doing today gives us a better chance of being able to do that as well,” she said.

The decision also comes after White House adviser Dr. Anthony Fauci and the U.S. surgeon general said the White House’s COVID-19 guidance amounts to a recommendation for a nationwide stay-at-home order.

Ivey’s new order will require Alabamians to stay at home as much as possible — except for essential outings like grocery shopping and getting medical care.

“No one is immune from this. It’s not even safe to go to our places of worship and congregate as we are so used to doing at this holy time of the year,” Ivey said.

Essential outings will include work at critical jobs, solitary exercise outdoors, buying food, going to the grocery store or getting health care or medicine. Those will still be allowed.

Attorney General Steve Marshall said Friday that the stay-at-home order will have the force of law and will be enforced as such. Criminal prosecution of those who do not comply is possible, but he said he hopes people will voluntarily comply.

“This is a time when we should be working together to get through an extremely difficult time,” Marshall said.

Last week, Ivey ordered closed until April 17 numerous types of businesses including athletic events, entertainment venues, non-essential retail shops and service establishments with close contact.

But she did not go as far as ordering residents to stay home.

In other ways, Ivey moved more quickly than neighboring governors. She closed the state’s beaches on March 19, before other states like Florida. She also ordered restaurants to limit service to take-out and delivery.

By last Friday, the state prohibited gatherings of 10 or more people and any gathering in which a six-foot distance could not be maintained between persons, but the order did not apply to work-related gatherings.

The governor and the state superintendent of education also closed schools for the remainder of the school year.

Ivey, unlike the governor in Mississippi, did not try to overrule cities and counties who issued curfews and stay-at-home orders. She said she supported them.

Before Ivey closed restaurants and some non-essential businesses last week, Jefferson County didn’t wait on state leaders. Health officers in Jefferson County — where the number of cases is high — issued more restrictive measures meant to keep residents safe during the pandemic.

Jefferson and Mobile Counties, however, are the only in the state to have independent health departments, with legal authority to act autonomously from the state health department.

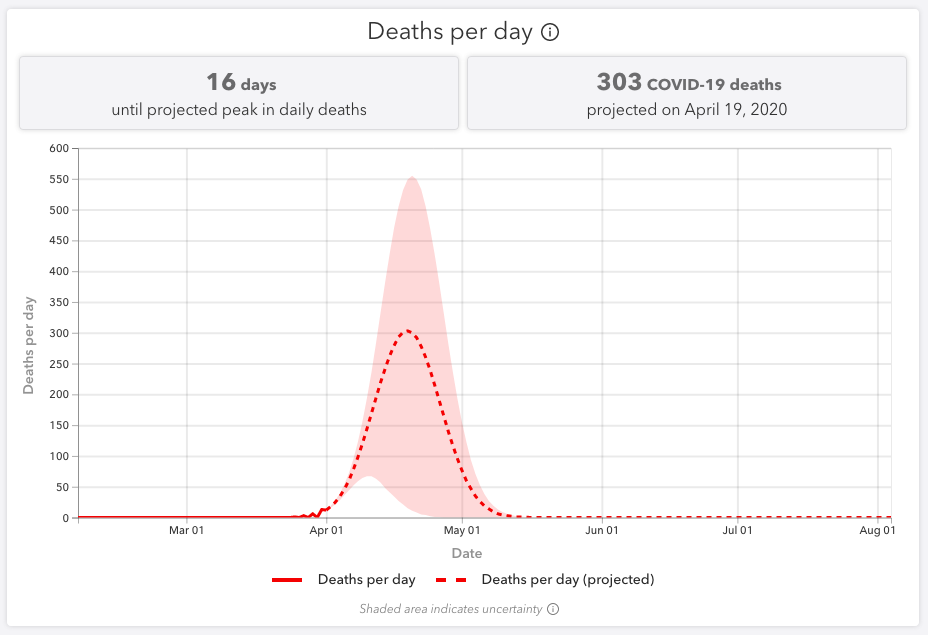

The new order comes as dire modeling from the University of Washington’s Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation estimate that Alabama could reach its peak of the outbreak by April 17 and it could be one of the worst-affected states.

At the height of the outbreak, the modeling suggests Alabama could see 303 COVID-19 deaths per day for a total of 5,500 deaths by August — much higher than most states. Alabama may also face a hospital bed and ventilator shortage by mid-April, the IHME projections estimate.

The model, which changes often based on the number of deaths reported per day, shows that Alabama could, at the height of its outbreak, see more deaths per day than Florida, Illinois or Texas.

Florida and Texas have more than twenty times the population of Alabama.

Some have suggested the IHME modeling, which has been cited by President Donald Trump and his coronavirus task force, are actually too optimistic.

Others say they are, for states like Alabama, worst-case scenarios. Different states have more data available for the model to work off. In Alabama, the outbreak is younger and fewer data points are available. FiveThirtyEight has explained why building models to predict pandemics is so difficult.

But experts at the University of Alabama Birmingham, including the director of the division of infectious diseases, Dr. Jeanne Marrazzo, have said the IHME modeling may be the worst-case scenario, but it is instructive.

Marrazzo is on the governor’s coronavirus task force. She’s warned that the state could be facing supply shortages and dire decisions if the outbreak is not contained. “This is not a hypothetical,” she said Thursday.

In the last two days, the model’s death projections for Alabama have been revised downward from more than 7,000 total deaths to 5,000. The models are live and will likely change again. For Alabama in particular, there is a lot of uncertainty in the model.

“I don’t know that the actual numbers are going to be correct or not,” State Health Officer Scott Harris said Friday. “I mean, they might be, and we’re doing our best to prepare for that.”

The light red area indicates uncertainty in the model.

But Alabama, like most southern states, is particularly susceptible to the virus because a high number of the state’s residents have underlying health conditions that make them more vulnerable to severe illness and death.

So far, about one in 10 deaths in the United States from COVID-19 has occurred in Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama and Georgia, according to data assembled by the COVID Tracking Project.

During a town hall with Sen. Doug Jones Thursday, Marrazzo suggested the state may need a stay-at-home order to send a clear message. Jones also called on Ivey to issue such an order.

“The reason I would like to see one is because it sends a strong message to the people of Alabama of how significant it is to use the social distancing, to use whatever means necessary to stop the spread of this virus,” Jones said Thursday.

As of Friday afternoon, Alabama had nearly 1,500 positive cases and 38 reported deaths.

Alabama Stay-At-Home Order by Chip Brownlee on Scribd