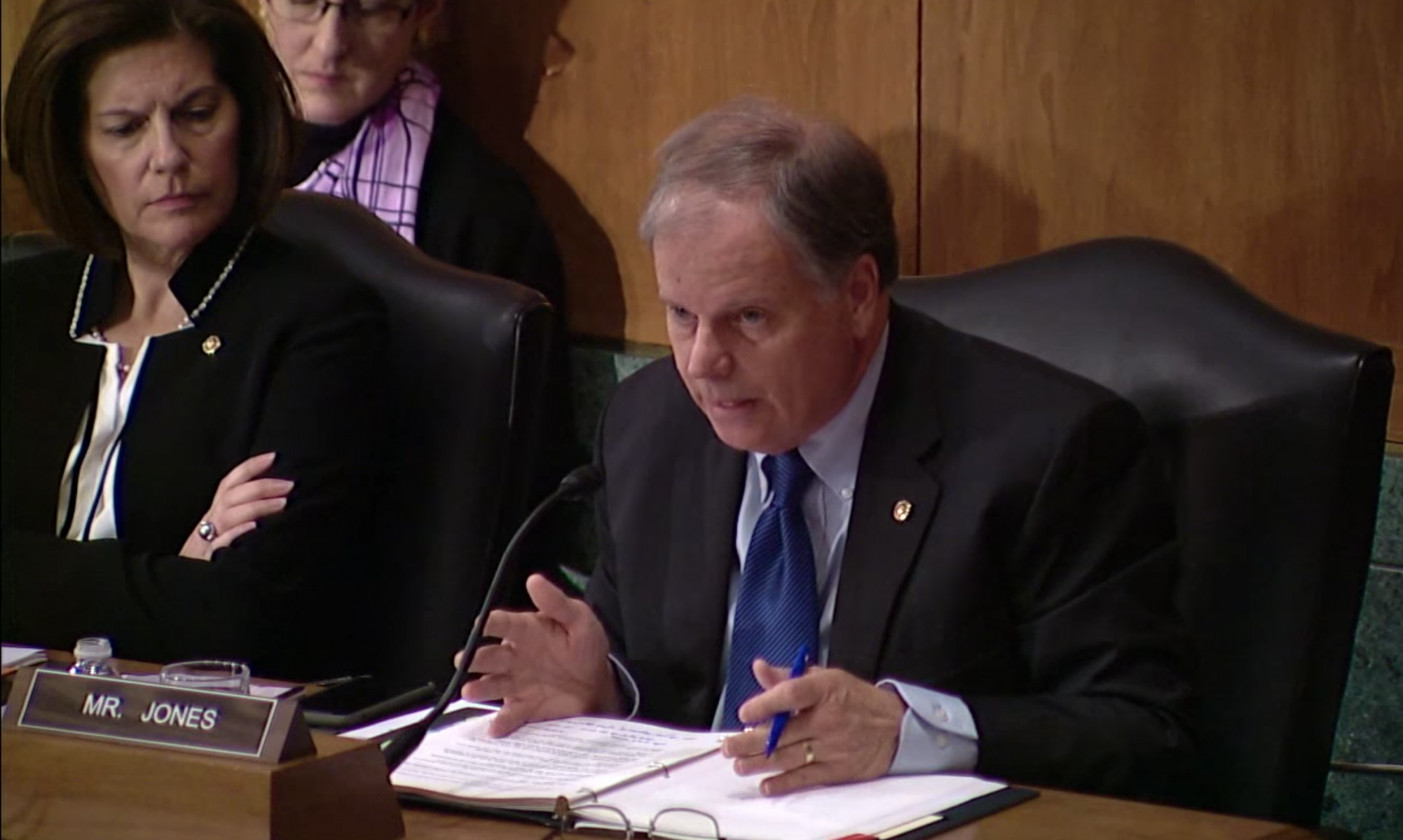

U.S. Sen. Doug Jones on Tuesday said “anything is on the table” as the country reels from the spread of COVID-19, state health officials rush to try to contain the outbreak and healthcare facilities prepare for an unprecedented strain on the country’s health system.

Jones said the Senate is likely to pass the House’s coronavirus relief bill soon, but they’re already considering what more they can do in the coming weeks to try to blunt the spread of the virus and avoid an economic depression. Economists already believe a recession is assured as state governments and the federal government tamp down on economic activity and some states close restaurants, bars and other retail establishments.

Alabama’s junior senator, who has been sounding the alarm on the coronavirus for weeks, said Tuesday that the Senate is considering direct payments to Americans to help stave off financial collapse. “I’m talking about U.S. Treasury checks,” Jones said.

“I think it’s important that we strongly consider direct, monthly financial assistance for working families during this emergency period in the United States,” Jones said. “By that, I mean a United States Treasury Check. I’m not talking about paid leave or anything like that. I’m talking about direct financial assistance.”

Jones also said he would push for childcare for health care works “so that they can continue to be on the frontlines.”

On Tuesday, President Donald Trump and his COVID-19 Task Force announced that federal resources might be used to bolster health care facilities, including using military personnel and military field hospital resources. Trump and Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin said Tuesday that the administration supports the idea of sending direct financial assistance to families amid the crisis as part of a massive economic stimulus package of around $850 billion.

“We’re looking at sending checks to Americans immediately,” Mnuchin said. “And I mean, now in the next two weeks.”

Experts are increasingly concerned that the country’s hospitals could be overrun with COVID-19 patients who require ICU beds and ventilators and that the health system may not be able to handle the load.

Jones said that if he was running the state, he would deploy the national guard and military reserves to begin planning to re-open closed hospitals across the state—particularly in rural areas—as a means of spreading out the workload placed on the state’s health care facilities.

“I think that all options ought to be on the table,” he said. “And we’ve got facilities there that can help people. It will be difficult getting them up and running, getting them clean, getting them in a spot where they can be used, getting them equipped to make sure that the beds have sheets and other things. I mean, it would be a lot, but I would like to think that we might be able to do that.”

He said hospitals should also begin canceling elective procedures to open up bed space.

The infectious disease specialist leading the UAB Medicine’s response to the coronavirus outbreak urged Alabamians to take social-distancing measures seriously to blunt the exponential growth of coronavirus cases in the state so as to not overload health care facilities.

On a call with reporters Monday, Dr. Jeanne Marrazzo from UAB said the closure of rural hospitals, the growth in the number of cases in the state and the potential for a ventilator or ICU bed shortage if the growth curve of COVID-19 cases isn’t blunted is “frightening.”

“In Italy, they don’t have enough,” Marrazzo said. “They are actually having to make decisions about taking people they believe are not going to survive off ventilators to reassign them to people. We do not want to be placed in that excruciating situation. It’s about the worst possible thing I can imagine as a physician, talking to a family about that or dealing with that. I don’t believe there’s any indication we’re going to get there. But again, my assurance is all based on my belief that we can deflect this curve and not be where Italy is right now.”

Marrazzo and Jones have both expressed concern that testing supplies are limited, and they have urged Alabamians who are not exhibiting COVID-19 symptoms—including a fever, cough, body aches, and shortness of breath—to not seek testing at this time. There are simply not enough supplies to test everyone, though they hope more supplies will be available by the end of the week.

“First of all, we’re seeing long lines in the drive-thru test center and people are still having trouble getting a test,” Jones said. “I’ve got a friend who sent me a text just a moment ago, who’s been trying to get a test for five days. Now she’s got symptoms, she’s got a fever, she’s got respiratory issues, but she can’t get a test. And that is in part because so many people are willing to get tests that don’t really have any symptoms and aren’t really sick. I’m not criticizing. What I’m asking people to do is to hold back if you don’t have a fever and respiratory issues.”

Just how bad that strain will get is not yet known. Experts have said that more than 50 percent of the population could become infected with COVID-19—some have placed that number higher at 70 percent. Research out of China indicates that about 15 percent of people who are infected require hospitalization and about five percent require intensive care. Alabama has a population of 4.8 million. So at some point, 120,000 could require intensive care in the state and 360,000 could require hospitalization.

“What we’re doing here is to work to make sure that we can get the resources to our health care workers, our small businesses and working families,” Jones said. “I’m very concerned about this situation, but I’m also confident in our ability to rise above any adversities—to rise to the occasion and stem the tide.”

One report pushed in London and sponsored by the government of the United Kingdom found that, in an unmitigated scenario, 2.2 million people in the United States could die because of hospitals being overwhelmed. It recommended intense social distancing and other virus suppression measures until a vaccine is developed for COVID-19.

That could last for a year to 18 months.