After a decade behind bars, all that came out of Holman prison was Antonio Bell’s body and a pair of new white Nikes, still wrapped in plastic.

Before he died on Jan. 9 of a likely drug overdose, 29-year-old Antonio told his family that it’s the guards who most often smuggle drugs inside. The family awaits a toxicology report, but statements to the family by prison staff indicate it was likely an overdose that killed him.

Bell’s family wants to know how a man being kept in a cell alone could have gotten the drugs that likely killed him, and have for years asked prison officials to look into two incidents in which they say correctional officers assaulted Bell. In one, nine other incarcerated men say they watched as an officer dragged a handcuffed Antonio down a flight of stairs.

Jason Britt, Antonio’s father, said his son made mistakes, but that his 20-year prison sentence on an escape charge “shouldn’t have been his death sentence.”

Now that he’s gone, his family continues to ask questions about how it happened, and hope that his death and the attention brought to it might help others still inside.

For Bell, though, he’s still angry about a system that failed to keep his son alive long enough for him to serve his time, and a system so broken that even getting his son’s body was an ordeal.

When the family was notified of Antonio’s death, Britt said he was told someone would call him the next day to walk him through the process of getting Antonio’s body and belongings, but that no one called. Britt said he called the prison later the next afternoon, a Thursday, and was told his body had been sent for an autopsy.

“So I was waiting on them to call me back to say his body is ready to we can make arrangements to get him home, but no one called,” Britt said.

He called the prison again on Monday and was told that his son’s body had been ready since Friday evening.

“That’s very frustrating. Where are your processes?” Britt said. “An inmate is still a human person.”

Britt retired from the U.S. Army after 20 years of service. He’d been in Antonio’s life since 1992, when his son was just a year old.

“He was outgoing even as a little bit baby. Full of energy and spirit,” Britt said.

When he was little, Antonio had a speech impediment and couldn’t pronounce words with “TR” well, Britt said.

“He was afraid of big trucks. When he’d see one he’d say ‘big ruck! big ruck!’” Britt said with a laugh. Speech therapy helped.

“Once they cleared that up he was a talker. From five or six years old he could hold a conversation with the oldest, most intelligent adult,” Britt said.

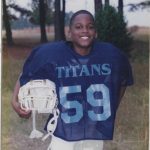

Antonio loved football. He was a middle linebacker, and big. At 6 foot and 190 pounds as a freshman, his high school coach asked him to play with the varsity squad.

Antonio traveled with the family from Britt’s first assignment at Fort Huachuca in Arizona, to Fort Gordon near Augusta, Georgia, then to Fort Carson in Colorado and on to the Atlanta area.

Antonio was an avid reader. Before the family moved to a new city, he’d read up on the place and tell the family what they’d need to see, where they could go, his father said.

In 2003, Antonio went to live with his grandmother, Elizabeth Wynn, in Tallahassee while her son was deployed to Iraq on one of several overseas tours.

Wynn said her grandson would travel with her for her job with the Florida Department of Children and Families. That summer, the two traveled to Jacksonville, Tampa and Fort Lauderdale together.

“He was just thrilled. He would help at the reception desk at the meetings,” Wynn said. “He will be there with the person handing out the name tags and talking to people, getting to know people. He just enjoyed that.”

She’s since moved to Atlanta, and said former coworkers and church members still ask about Antonio, and remember the bright, confident, curious young man whom they met in 2003.

As he got older, Antonio began getting into trouble. Minor things, his father said, but in 2009, it got worse.

On July 4, 2009, Antonio was speeding while driving through Abbeville in Henry County, headed to visit family in Florida. The car was stolen, Bell said, although police later determined that Antonio wasn’t the person who stole it. He was arrested, taken to the Henry County jail and later charged with speeding, eluding, possessing a firearm and receiving stolen property, according to court records.

“So my wife and I thought, and this is the hard part to talk about, we decided that it would be best not to bail him out. Maybe it’ll teach him a lesson,” Britt said.

Seventeen days after being arrested, Antonio hit a sheriff’s deputy in the county jail and tried to escape, according to court records. He tried to escape again in November using a makeshift key to try and remove handcuffs while at a court hearing, according to those records. In August 2010, Antonio pleaded guilty to the escape charge and was sentenced to 20 years, according to court records.

Antonio spent about a year in the Limestone Correctional Facility, spent time at the William E. Donaldson prison and at St. Clair prison in Springville, before being transferred to the notoriously violent Holman prison.

“We would talk to him and he’d say ‘Daddy. I can’t even begin to explain to you how it is here. The stuff that we see on TV. That’s not real, Dad. You’ve got to be ready at all times. Everybody has weapons,’” Britt said. Antonio also worried that there weren’t enough correctional officers to keep peace, and told his father that understaffing was increasing the dangers for everyone.

Antonio’s concerns were mirrored in an April 2019 report by the U.S. Department of Justice detailing the agency’s lengthy investigation of state’s prisons for men, which showed the state was failing to protect men from rampant sexual assaults, violence and homicides. Federal investigators noted understaffing and an inability to keep contraband out of prisons.

Alabama’s prisons are full of dangerous drugs, the U.S. Justice Department found, which noted in the report that “ADOC prisoners are dying of drug overdoses and being subjected to severe violence related to the drug trade in Alabama’s prisons.”

Synthetic cannabinoids, known as synthetic marijuana or “flakka”, was prevalent in prisons, investigators found. Between December 2016, and August 2018, the federal agency found that 22 incarcerated men died of synthetic cannabinoid overdoses, and in the first half of 2018, when the ADOC stopped producing documents for the Justice Department, at least 10 men died from the drug.

An ADOC Intelligence and Investigation Division investigators told federal authorities that “without a doubt” the largest way drugs were entering prisons was by staff smuggling them in. Correctional officers weren’t being searched upon entry into prisons, the report found, and ADOC policies weren’t able to control the problem.

Drug use at Holman prison was out of control, federal investigators found.

“Two shift commanders of death row and segregation at Holman estimated that 50- 60 percent of their prisoners were using drugs. One shift commander over general population at Holman estimated that 95 percent of that facility’s prisoners were using drugs,” the report reads.

During a joint state House and Senate budget hearing on Jan. 23, Dunn was asked by a legislator how contraband was getting into the prison, Dunn said that it was coming in in a variety of ways.

“Some of it is thrown over the fence; We have challenges in the visitation area; and there is an aspect where we have staff that are engaged in criminal activity by bringing in contraband,” Dunn said.

Dunn said during the hearing that over 70 correctional officers have either been arrested or dismissed for bringing in contraband in the previous three years.

“We do routine searches in our parking lot and our staff as they come in and out of the facility,” Dunn said during the hearing. “We have increased that.”

Asked how many correctional officers had been arrested for crimes related to contraband between 2017 and 2019, ADOC spokeswoman Samantha Banks wrote in a response to APR on Feb. 20 that 15 correctional officers had been arrested during those years on charges related to contraband.

“We aggressively will investigate all allegations of corruption, including contraband trafficking, as soon as we are made aware. We hold each member of our staff to the highest standards of law enforcement. Any ADOC employee who commits a violation will be prosecuted to the full extent of the law,” Banks wrote.

Asked for clarification on Dunn’s statement to legislators that 70 correctional officers had been arrested or dismissed during those years for contraband, Banks on Monday told APR that Dunn’s figure included correctional officers and prison staff arrested for any crime, not just for contraband.

Banks said Monday she was uncertain how many of the 70 may have been fired but not charged with crimes related to contraband, and that ADOC staff would have to research the matter more.

Antonio had hoped that he could get out of the violent prisons on parole, and in a letter he wrote to Alabama Bureau of Pardons and Paroles Board members in June 2016, just 17 days before his case was to go before the three-member board, Antonio pleaded for them to look beyond what his paper record might show.

“In these twenty-five and a half years of my life, I’ve learned that just because a person has eyes doesn’t necessarily mean they can see,” Antonio wrote in the letter. “…I think you all should be provided a closer look into the minds of Alabama State Prisoners and the environment they are subjected to; because it isn’t just for the sake of the people like me or our families, it’s for the sake of the betterment of society as a whole.”

“Young men are coming to prison and are leaving in worse shape than they came. That really saddens me. The Alabama Department of Corrections needs changing and I’m dedicated to helping it,” he wrote.

Antonio’s words likely never made it to Parole Board members. Days before his hearing, he got into a fight with another inmate and his parole hearing was canceled, Britt said. He did get a parole hearing in 2017, but was denied.

Britt said he was scheduled for another possible parole hearing in September of this year, and that “we thought he had a good chance.” He was being kept in segregation, he said, so there was less chance of him being caught up in a fight, but it wasn’t to be.

The Britts received a call at home from another incarcerated man in May 2014, who said that they needed to come check on Antonio.

Soon after, the Britts were allowed to visit him in prison, but were told only one of them could do so, so Britt said his wife, Terrell LaRita Britt, entered to see that Antonio’s head was bruised and bandaged. He had cuts to his face and told his Mother that correctional officers had beaten him, Britt said.

The family asked prison officials and investigators with the ADOC’s Investigations and Intelligence Division to look into the matter, Britt said, but never received a response.

Three years later, on March 8, 2017, Britt said Antonio was again assaulted by correctional officers at the Donaldson Correctional Facility.

A disciplinary report signed by correctional officer Zackery McLemore on March 9, 2017, states that the day before Antonio was ordered to “lock down inside your assigned cell” and failed to do so. He was charged with failing to obey a direct order, according to the document.

Statements signed by nine other inmates and given to APR by the family describe the incident in detail. Those inmates say they witnessed Antonio trying to “lock down” in his cell but that he was called outside the cell by a correctional officer, who pepper sprayed Antonio, handcuffed him and hit him along with other officers before one officer dragged him down a flight of stairs while in handcuffs.

“He was helpless, and didn’t do anything to be beaten in that manner,” wrote one of the incarcerated men. “To restrain a person is an orderly procedure, but to beat a person is brutality, and from what I witnessed (on March 8, 2017) was police on inmate brutality.”

Another incarcerated man wrote that a female correctional officer working in a cubical came out once Antonio was handcuffed “ran up the stairs and kicked inmate Bell in the face three times” while two other male officers punched him repeatedly. He wrote that another correctional officer “grabbed inmate Bell around his neck (while handcuffed behind his back) and drug him down the flight of stairs. After being drug out of my sight I then heard inmate Bell screaming in agony.”

APR is not naming the other incarcerated men who signed statements to prevent any possibility of retribution against them. Antonio considered, but never filed, a lawsuit in the matter.

Britt said he again contacted ADOC’s Investigations and Intelligence Division and asked that they look into the incident, but that he never got an answer.

His parents bought him the pair of white Nikes on Nov. 27, 2018, through the prison purchasing system, but soon after, they stopped hearing from him.

In early 2019, after being kept in segregation for many months, Antonio stopped responding to letters and wouldn’t take calls.

Wynn said she kept writing to her grandson regardless, but he wouldn’t respond.

“I would say, ‘even if it’s not a letter, just something on a piece of paper in your hand writing,’ I just need to know, you know?” Wynn said. “I always would tell him, ‘you know I got money on your books. You can call me. Call collect.’ I don’t know what happened.”

She kept all of his old letters, and in one, written while he was at the Limestone prison, Antonio wrote about all the classes he was able to take there and that he was told he was going to be sent back to Holman prison where he’d previously been, and was worried about it, Wynn said. She encouraged him to try and stay at Limestone for as long as he could.

“After he got back down there he did write me this letter. He said, Grandma. You were right. I should have stayed at Limestone as long as they would let me, because Holman…was not like it was then, so that gave me a clue that it is terrible.”

In a letter to his grandmother on Nov. 30, 2015, Antonio wrote to thank her for a birthday card he’d gotten with a special note from her, which he said had “been read several times.”

“Lately, I’ve been keeping a journal mainly for the purpose of understanding my thoughts & feelings,” Antonio wrote. “I’ve been incarcerated since 7-4-09 and I’ve yet to accept that. I constantly frustrate myself because my mind is everywhere but here.”

“I can’t continue to put myself through this Grandma, so I’ve decided to let go. Dying before I get the chance to do everything I want to do in life has always been one of my fears,” Antonio wrote.”But I’ve learned the painful lesson that I’m probably not going to do a third of what I want to do.”

On Oct. 3, 2019, the Britts wrote a letter to Holman prison warden Cynthia Stewert, Gov. Kay Ivey, ADOC commissioner Jeff Dunn and to the U.S. Department of Justice Civil Rights Division expressing concern that despite their attempts since August to reach their son, or someone at the prison who could put their minds at ease, they’d received no return calls to verify that he was alive and well.

“Please respond to us via letter and/or telephone call regarding Mr. Bell’s welfare and let us know for certain that he is not in any way incapacitated such that he cannot respond to our letters nor place collect telephone calls,” the Britts wrote. “We just need to know that he is alive and well! Again, we are gravely concerned that something has happened to Mr. Bell and we, his family, has not been notified.”

Not long after sending the letter Antonio’s mother received a call from prison staff who said that Antonio was on the line as well.

“Ma, I love you to death. You hear me ma? I love you to death,” Antonio told his mother, adding that he wasn’t a “dope fiend.”

Britt said that after his death prison staff told the family that Antonio had given all his belongings away, except for the shoes.

He’d had many books the family sent him over the years, Wynn said, and they knew he kept a journal. Surely he’d have given away the shoes as well, she wonders.

The family can’t be certain, however, that Antonio, who was being kept in segregation, received the shoes from prison staff before he died.

“He was a human being. He was not just one of those numbers, and I think that’s how people see it,” Wynn said. “Put all of the prisoners in the same boat, you know. They deserve it.”

Wynn said her grandson was a young man when he entered Alabama’s prisons, and that the years went by “in an environment that was not rehabilitative. Just warehousing people.”

“We are hurt. Devastated,” she said.

The family asks that those who wish to do so donate in Antonio’s name to the Montgomery nonprofit legal advocacy organization Equal Justice Initiative by visiting here.