A bill passed by the Alabama Senate last week lawmakers say will help keep pets trapped in hot cars safe, might actually endanger the animals, according to some animal advocates and veterinarians.

That bill was written by a dog breeder who some worry purposefully wrote the bill to make it harder to keep animals safe, and to instead protect breeders from having animals confiscated, they told APR this week.

Mindy Gilbert, The Human Society’s Alabama state director, told APR by phone on Tuesday that she’s certain that the senate bill’s sponsor, Alabama Sen. Jimmy Holley, R-Elba, “does have good intentions, but I think the devils in the details.”

Several attempts this week to reach Rep. Holley were unsuccessful.

The bill would grant criminal immunity to a civilian who rescues an animal from a vehicle, and would provide civil and criminal immunity to first responders who do so. The legislation also makes it a misdemeanor crime if a pet dies in a hot car.

Gilbert said that while those might also sound like great ideas, the bill would actually reduce criminal penalties for allowing a pet to die in a hot car.

“Our current cruelty statute, which has been used in cases like this, would define that as a class C felony,” Gilbert said.

A Trussville woman in 2018 was charged with felony aggravated cruelty to animals for leaving her dog in a locked car while shopping in Walmart. The dog died after police broke out a window and removed the distressed animal.

The bill also states that the ambient temperature of the interior of a vehicle must be 99 degrees or hotter to be charged under the legislation.

Gilbert said she’s spoken with numerous veterinarians who all said that 99 degrees is too hot to be safe for pets trapped in cars.

Gilbert said that for many breeds of pets, and pets with compromised health, “that requirement in order to rescue them will absolutely sentence them to death,” and there are other aspects of the bill that trouble her.

“I think everybody was very focused on providing immunity to first responders, which I think is fabulous,” Gilbert said of the legislation, but worried that it doesn’t include animal control personnel in its definition of public safety officials and covered by the bill’s immunity clause.

Holley’s legislation defines public safety officials as “An individual employed by a law enforcement agency, fire department, or 911 emergency service.”

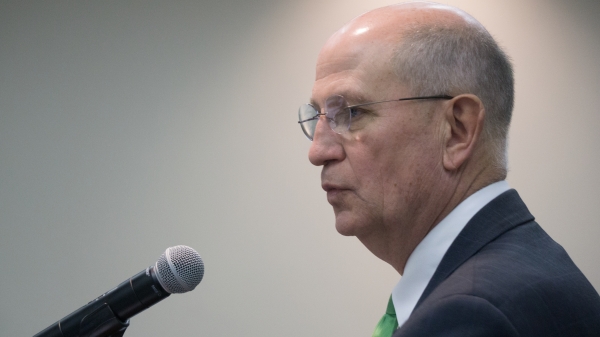

Dr. Mark Colicchio, a veterinarian in Spanish Fort, reached out to Sen. Holley and all of the members of the state Senate Judiciary Committee about his concerns with the bill prior to its passage in the senate. Holley put Colicchio in touch with the man he said wrote the bill, Norman Horton.

Colicchio said he spoke to Horton, owner of the Dale County german shepherd breeding company Triple S Shepherds, at length about his concerns, but that none were addressed in the final legislation.

“There are a lot of temperature references in there which make no sense whatsoever,” Colicchio said.

Colicchio said he spoke with Horton about the bill’s language that required the ambient temperature of the interior of a vehicle to be 99 degrees or higher before a person could be charged. He said he told Horton that there’s no practical way for a public safety official to measure the ambient temperature inside a locked vehicle from outside, to which he said Horton suggested they call carry digital temperature readers.

Such devices measure surface temperatures, and wouldn’t be able to read the temperature inside a locked car, Colicchio said.

After speaking with veterinarians at Auburn University’s College of Veterinary Medicine Cholicchio said they looked at data that suggested that if the outside temperature of a vehicle, which can be more easily measured, was 78 degrees an animal trapped inside with no ventilation could be in jeopardy.

Colicchio said he suspects the legislation was purposely written to protect owners from having their animals taken from them in the event they’re left in hot cars.

“He doesn’t want breeders to risk having their valuable dogs stolen out of the car because somebody thinks they’re at risk,” Colicchio said. “…When you structure a law to benefit yourself, and animals suffer for it, that just gets to me.”

Horton, speaking by phone Wednesday, told APR that he wrote the bill to protect animals and to establish the proper way to rescue an animal in distress.

“This is America, and this is Alabama, and if someone’s gonna be guilty of a crime or charged for a crime then they need to have committed that crime” Horton said.

Horton said “we don’t need vigilante justice” so he wrote the bill to make clear how best to enter a vehicle if an animal is in need of help.

Asked how he decided that 99 degrees inside a vehicle was the temperature at which a pet was in danger, Horton said “I got the figure after talking to several veterinarians.”

Asked which veterinarians he spoke to get that figure, Horton said “that’s immaterial” and declined to name them.

Horton likened the matter to speed laws, and said while some speed limits are set at 70 MPH, some people, such as police officers, can drive safely at speeds up to 113mph.

Asked why the bill doesn’t include animal control officers in the immunity protections, Horton said that “it does.”

Horton pointed to the bill’s language that defines public safety officials as “An individual employed by a law enforcement agency” and said “go to Tuscaloosa. Go to any of the cities around, and animal control officers are employed by the police department. They’re sworn officers.”

Some animal control officers who work in municipal law enforcement agencies are sworn officers, Gilbert said, but many are not, and in the counties, where animal control is operated as stand-alone agencies, animal control officers are not sworn officers and wouldn’t be immune from prosecution under the legislation.

Asked why his bill didn’t include all animal control officers, whether they were sworn officers working in law enforcement agencies or not, Horton suggested that it was to ensure owners could be charged with crimes

“Do we want to charge for the crime when they do something like this or just let them go?” Horton said.

Horton declined to answer a question about the bill’s language that limits the charge of killing an animal in a hot vehicle to a misdemeanor and soon after ended the interview.

“It’s not to help the animals,” Colicchio said of the legislation. “That’s the wolf in sheep’s clothing.”

It was unclear Wednesday if Holley’s bill had a sponsor in the state House. There were no similar bills filed Wednesday, according to the state Legislature’s website.