Recent news coverage in major outlets of the story of Alabama death row inmate Toforest Johnson’s case is giving his family hope that he’ll get a new trial and a chance at freedom.

The family awaits a judge’s ruling on whether he could get that new trial.

“It’s especially difficult around the holidays,” said Johnson’s 27-year-old daughter, Shanaye Poole, speaking to APR on Tuesday. “But we just have to continue to stay positive and maintain hope. I feel like that’s all we’ve really had for all these years, is hope that eventually justice will prevail.”

Poole was just five-years-old when her father was sentenced to death in connection with the July 19, 1995, shooting death of Jefferson County deputy William Hardy outside a hotel, where Hardy was working as a security guard.

Prosecutors in his case presented no physical evidence or eye witnesses tying Johnson to the shooting, and instead built the case around testimony from a single witness, Violet Ellison, who said that while eavesdropping on a phone call from a man in jail she heard an inmate who she thought to be Johnson admit to the shooting Hardy.

A Sept. 5 opinion essay in The Washington Post described a trial rife with problems and a witness who received $5,000 from the state to testify against Johnson, a fact that wasn’t made known to defense attorneys at the time.

Johnson and a friend, Ardragus Ford, were both charged and tried separately for Hardy’s murder.

In Ford’s trial prosecutors said Ford pulled the trigger. In Johnson’s prosecutors said Johnson was the shooter. Ford was acquitted and Johnson’s first trial ended in a hung jury, but a second trial in 1998 resulted in him receiving the death penalty.

Both Ford and Johnson’s charges stemmed from statements made at the time by a 15-year-old girl who later admitted under oath that shed lied to police because she wanted the reward money and because she felt pressure from police, according to The Appeal.

Johnson’s family now awaits a decision by Jefferson County Circuit Court Judge Teresa Pulliam, who ruled over a hearing on June 6 in which Johnson’s attorneys argued that he deserves a new trial because of the prosecution’s failure to disclose at the first trial that the witness would be paid reward money.

Johnson’s attorneys argued that the prosecution’s failure to disclose ran afoul of the Brady doctrine, a court precedent that establishes that prosecutors must turn over all evidence that might exonerate a defendant, including any evidence that goes to the credibility of a witness.

At the June 6 hearing Ellison testified that she hadn’t known about the reward money when she testified in the 1998 trial, according to WBRC 6, and had only learned about the money in 2001 when the District Attorney’s office contacted her about the $5,000.

Johnson’s attorneys argued that it was unlikely Ellison didn’t know about the reward money due to extensive news coverage at the time and the fact that Ellison knew Hardy and his wife, according to WBRC 6.

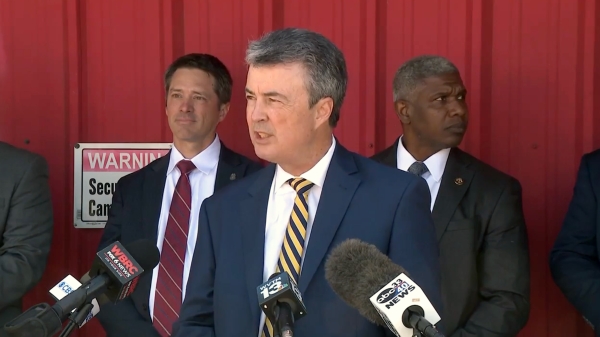

His attorneys told the court that they’d learned that there might have been reward money in 2003, but that the state didn’t disclose that fact until January, when Attorney General Steve Marshall’s office produced documents about the reward that the DA’s office said had been “misfiled.”

One of those documents was a letter from then-Jefferson County District Attorney David Barber to then-Gov. Don Seigelman on Aug. 7, 2001, asking him to award the $5,000 to Ellison. The letters stated that Ellison “pursuant to the public officer of a reward, gave information leading to the conviction of Toforest Johnson…”

On Dec. 12 The Innocence Project, a New York-based nonprofit that works to exonerate the innocent, filed a brief asking the court to grant Johnson a new trial based on the Brady doctrine and what the nonprofit said are numerous other problems with Johnson’s conviction.

“If ever a case bore the hallmarks of a wrongful conviction, Toforest Johnson’s is it,” wrote attorneys for the nonprofit to the court. “…Over the course of three years, the State presented five different theories regarding who killed Deputy Hardy.”

Attorneys for The Innocence Project also note in the court filing that the prosecutor during Johnson’s trials has since testified that he has doubts about the strength of the state’s case against Johnson.

“In 2014, prosecutor Jeff Wallace testified under oath that he “[did not] think the State’s case [against Mr. Johnson] was very strong . . . because it depended on the testimony of Violet Ellison,” the court filing reads.

Ty Alper, one of Johnson’s attorneys, sent a statement to APR on Monday on the pending court decision. Johnson is represented by attorneys with the Death Penalty Clinic at U.C. Berkeley School of Law and the Southern Center for Human Rights in Atlanta.

“This will be Mr. Johnson’s 25th Christmas locked up, away from his family. What we want now for Mr. Johnson is a fair trial in front of a jury that hears all of the evidence,” Alper’s statement reads.

If Pulliam grants Johnson a new trial it will be up to Jefferson County District Attorney Danny Carr to decide whether to prosecute.

Carr, elected to office in Nov, 2018, became the county’s first black district attorney, and ran on a platform of building credibility for the office among the community and increasing transparency, according to several news accounts.

According to a questionnaire created by the Fair Punishment Project that Carr filled out prior to his election, Carr agreed to establish a special unit tasked with examining post-conviction cases to “identify and correct wrongful prosecutions.”

Carr hasn’t made public statements about Johnson’s case, and APR’s questions to Carr’s office on Monday hadn’t been answered as of Tuesday evening.

“I believe in my Dad. I know that he is innocent,” Poole said, speaking to APR on Tuesday.

“I’ve never heard him complain. Not once. He’s been able to find light in such a horrific situation,” Poole said. “So we just have to confide in each other and love on each other until he’s able to come home.”

Recent coverage of Johnson’s plight by The Washington Post and The Appeal have given the family a new sense of hope, Poole said.

“Finally we’re getting some traction. Finally the world is able to hear my Dad’s story, and it needs to be heard,” Poole said.

Now 27, Poole graduated from the University of Alabama in 2014 and works as a pharmaceutical representative. She said she, her three brothers and her sister hope the new district attorney, Danny Carr, can help her family receive long-awaited justice.

“Danny has an opportunity to right a terrible wrong and we are hopeful that given the history of this case he will take action and after all of these years my father will receive the justice that he deserves,” Poole said.

Poole described her father a “strong-minded” and ever hopeful, as someone who throughout his years at the Holman prison in Escambia County as kept his own hope alive that he’d be free one day.

“He’d rather think of the positive outcomes than the negative,” Poole said of her father. “That could eat away at a person, but I think he’s just maintained his faith and he knows that he is an innocent man.”