For the entire 30 years of its existence, I’ve been following the Annie E. Casey Foundation’s KIDS Count Data Book and how Alabama fares each year. The 2019 report was issued back in the summer, and overall, Alabama ranked 44th in the nation where child well-being is concerned.

Alabama is always in the bottom 10. The state bounces around one or two or three places, one way or the other, but never shows great improvement in the welfare of its children compared to other states.

I’ve said this before: If Alabama were a parent, it could be arrested for child neglect, if not child abuse. For 30 years, state officials – policymakers, governors, legislators – have had detailed reports on how well our state’s children are doing. For 30 years, we roll up and down in the bottom 10.

This year, in fact, Alabama fell two places, from 42nd to 44th in the nation.

Sure, there was some good news.

As APR’s Eddie Burkhalter reported Wednesday, some state indicators improved, despite the overall low ranking. “The state’s infant mortality rate is at an all-time low in 2017, when Alabama’s infant mortality rate was 7.4 per 1,000 live births, down from 9.1 percent in 2016, but the black infant mortality rate remains the highest, despite declining from 15.1 per 1,000 in 2016 to 11.3 in 2017,” writes Burkhalter.

Yet, in other categories, Alabama didn’t budge very much.

The rub is that we’re just not keeping up with what other states are doing. We have the data. We know what other states do.

Yet, in Alabama, our lawmakers pass anti-choice bills to ensure more births – though child populations in Alabama are mostly declining, and not because of abortion – but after a child is born, it’s nearly every kid for him- or herself.

The child poverty rate in Alabama is 26 percent. Food insecurity for children has dropped only a few percentage points over the past decade, but food stamp recipients have fallen more than 100,000.

Food insecurity is a serious problem, but state officials (and those in Washington as well), especially Republicans, do what they can to prevent people from getting food assistance.

Fortunately, we do have groups like Voices for Alabama’s Children, which publishes the state KIDS Count data book, campaign for policies that’ll help the state’s children.

“Not one specific thing is going to fix all of these things, and it’s definitely not going to fix them overnight, but a combination of all of us working together and a combination of policies working together can definitely make an impact,” Angela Thomas, communications manager for Voices for Alabama’s Children, told Burkhalter.

There’s no doubt, however, that Alabama can do more. The yo-yoing in the national rankings is frustrating, but in all sorts of quality-of-life indicators, Alabama ranks poorly.

The state’s infant mortality rate is at an all-time low, sure, but Cuba’s infant death rate is 4.4 per 1,000 live births, three full percentage points below Alabama’s 7.4. Is Cuba’s prenatal care and health care system that much better than Alabama’s? Or even the United States’ health care system? As a nation, the United States’ infant death rate is 5.8 percent.

We do OK in football, perhaps. But we should aspire to do more for our kids. All of them, and not just those who live in stable families.

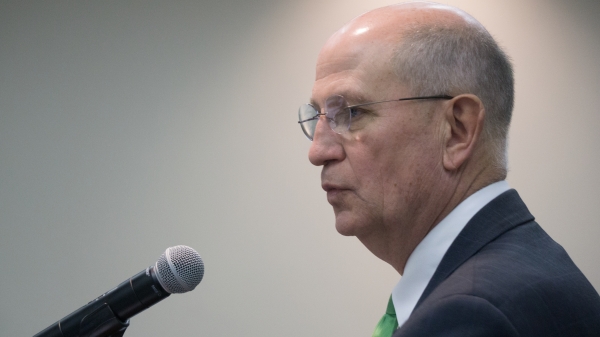

Joey Kennedy, a Pulitzer Prize winner, writes a column every week for Alabama Political Reporter. Email: [email protected].