Montgomery– Alabama’s prisons are overcrowded, violent and the living conditions horrid, but the fixes aren’t going to come easy, according to the director of the state’s Sentencing Commission, speaking to the Governor’s Study Group on Criminal Justice Policy on Thursday.

Alabama’s prison system is under threat of federal takeover if the state doesn’t remedy the state’s overpopulated, violent prisons, but the solutions are complicated, said Bennett Wright, director of the Alabama Sentencing Commission, to the study group’s members at the State House on Thursday.

“There are no simple, no easy and no free fixes,” Wright said.

The Governor’s study group was formed by Ivey’s executive order in July to help the state settle on fixes to its ailing prison system. According the order that established the group it is to disband on the first day of the 2020 legislative session, which is Feb. 4.

The U.S. Department of Justice in April wrote a letter to the state informing leaders that there was reason to believe Alabama was violating prisoners’ Constitutional rights to protection from physical violence and sexual assault while incarcerated by housing them in understaffed, unsafe facilities.

The letter from the DOJ came while the Alabama Department of Corrections was already facing a lawsuit in federal court over inmate medical and mental health care, and lawmakers continue to struggle with overcoming drastic shortages in correctional officers working in aging facilities. The state is under court order to add an additional 2,200 correctional officers.

State lawmakers passed sentencing reforms in 2013 and 2015, which resulted in a decrease of inmate population from about 200 percent of capacity to around 160 percent. Between 2013 and 2018 Alabama’s prison population dropped from 26,293 to 20,618.

While the number of inmates dropped in those years, the population has recently increased.

ADOC data that shows that in April 2019 the state’s in-custody prison population was greater than the previous year by almost 300 inmates, which was the first time that’s happened since February 2013. In June, the ADOC recorded 639 more inmates than the state held in custody the previous June.

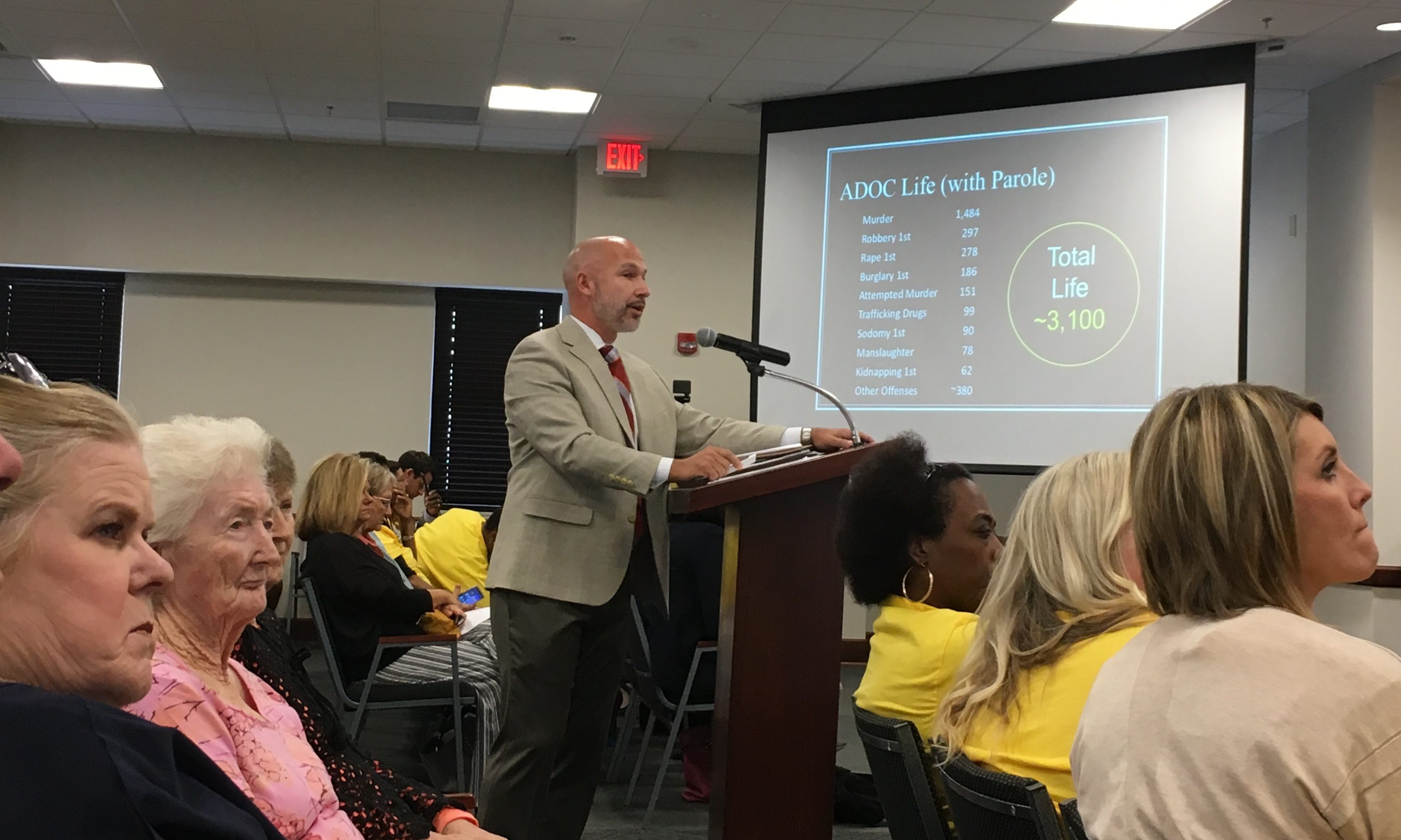

There are about 1,500 inmates serving life without the possibility of parole, Wright said, and about half of them were convicted of capital murder. Of the remaining inmates, 240 are serving for murder convictions. Wright said 21 inmates are serving life without parole sentences for drug offenses.

Of the 3,100 serving life sentences with the possibility of parole 99 inmates were serving for trafficking drugs, according to figures provided by Wright.

Wright described those previous reforms as “mammoth pieces of legislation” that he said covered “whole swaths of individuals.” What reforms left that could be addressed are smaller changes, he explained, that would affect a smaller percentage of inmates.

In 2015, changes to the rules regarding technical parole violations meant that those on probation or parole who commit a technical violation — anything other than a new offense — could only be sanctioned for up to 45 days, but had to serve that time in prison instead of county jails.

In 2018, there were about 9,400 inmates admitted to Alabama prisons, and of those 2,800 were admitted because of technical parole violations, Wright said, which was about 30 percent of all new admissions.

Wright said those serving on technical parole violations serve very short sentences, however, so removing that portion of the prison population would have little impact on the overall, long-term prison population. Lessening the numbers of those inmates would reduce costs to Alabama Department of Corrections (ADOC) for processing those inmates, however, he said.

Wright said that while the state does pay for inmates serving sentences for felony crimes, it does not pay counties for those serving in jails for misdemeanors. If legislators were to decide to reclassify some felony violations to misdemeanors to reduce the prison population, the cost of keeping those inmates would fall to counties.

“The counties want to know is this going to be an unfunded mandate or is money going to follow that policy mandate from the legislature,” Wright said. “…That’s always the elephant in the room with felonies and misdemeanors.”

What if the state were to make some of the previous sentencing reforms retroactive, to cover inmates currently serving for crimes that, if convicted today, would not result in prison time? Wright said doing so would set free about 420 inmates.

“None of the answers are easy, and none of them have huge effects either,” Wright said. It would take multiple policy changes to make a dent, he said, and “none of which are easy.”

State Rep. Chris England, D-Tuscaloosa, a member of the study group, asked Wright whether the state followed those previous sentencing reforms with additional money to pay for the kinds of services that keep people from serving prison time.

“Alabama increased funding for more probation officers,” Wright said, but he added that Alabama struggles when it comes to funding programs and services to reduce recidivism, such as mental health and substance abuse treatment, and vocational training.

“As a state, we have pockets that do exceptionally well and we have pockets that do absolutely nothing” Wright said.

“We have absolutely failed,” England said, speaking of the Legislature’s funding of the state’s prison system and programs and policies to fix its problems. All of the state’s agencies that are supposed to be working together to reduce recidivism are fighting for the same dollars, he said.

The poorest among us cannot afford to pay for the probation services to keep them out of jail, England said, while those who can afford it front the cost of the state’s court system.

“When we see the populations exploding, of people who go in and out of jail without getting any needed resources or services or help, what ends up happening is not only do we fail that person,” England said, “but we fail the community that surrounds them.”

Despite gains in reducing the inmate population through previous sentencing reforms, some groups and concerned citizens worry that further substantive changes are needed.

Members of Alabamians for Fair Justice, a coalition of advocacy groups, faith leaders and citizens, met at the State House an hour before the study group meeting and discussed the need for further sentencing reforms.

Alabamians for Fair Justice is made up of 12 groups, including the ACLU of Alabama’s Campaign for Smart Justice, Alabama Appleseed, The Southern Poverty Center Law Fund, Alabama Arise, Greater Birmingham Ministries, Faith in Action Alabama and others.

Carla Crowder, director of Alabama Appleseed Center for Law & Justice, a nonprofit legal advocacy group and a member of the Alabamians for Fair Justice, said at a press conference prior to the study group meeting that the prison problem is dire.

“Our elected leaders have refused to adopt real, meaningful reform, and the crisis gets worse,” Crowder said. “We are counting on leadership from Governor Ivey’s criminal justice study group to finally make meaningful change, and we’re here to help.”

Crowder said the group presented the state’s study group with policy proposals, which are also posted on the group’s website here.

As the state’s prison population has increases in recent months, an important relief valve has been shut off. The state’s pardon and parole board hearings were suspended in September, and officials have said they won’t resume until at least November 1.

The bureau’s director, Charlie Graddick, has said notification requirements weren’t previously being handled properly, but the suspension of hearings came after much turmoil at the board following the 2017 parole of an inmate serving time for non-violent crimes who was later charged with capital murder in the deaths of three people.

Ivey signed into law changes that allowed her to appoint a director, among other changes, and after appointing Graddick he promptly put his predecessor and two other staffers on administrative leave “pending investigation into allegations of malfeasance.”

The Board chair, Lyn Head, resigned in September and had previously voiced concern to staff about what she said were attacks on the board by the state legislature.

Head, an attorney and former prosecutor, told AL.com after her resignation that she did not believe the agency was broken.

Speaking after the study group meeting, Crowder told APR that she was encouraged by discussion about the need to properly fund mental health and drug treatment programs outside of prisons, and about problems with the “pay-to-play” incarceration diversion programs, but that there is still work to be done on sentencing reform.

“What was a little discouraging was some of the discussion about numbers, that it was just 400 here or 500 here. Like that won’t make a difference,” Crowder said. “Those are human beings who are living in the worst prisons in the country.”