Investment banking powerhouse Goldman Sachs’s recent report predicts climate change will drive the “largest infrastructure buildout in history” as cities spend big to mitigate rising seas, flooding, increasingly strong storms longer and more intense heat waves and threats to food and water supplies.

The report by Global Market Institute, Goldman Sachs’ research think tank, states that while some cities can afford to invest in infrastructure to mitigate the impacts of human-caused climate change, other cities cannot, and researchers predict the disparities could drive human migration and disrupt local economies.

Greenhouse gasses are causing global temperatures to rise, the report notes, and we’re already seeings signs of rising seas, increased flooding, more intense weather events, pressures on food and water, shifting agricultural patterns and human health problems.

“…in fact, our own review of global temperature data over the last 60 years supports the view that the earth has already warmed,” the report’s authors wrote. “And if the scientific consensus is correct, the negative consequences of a warming world may well play out over several decades to come, even if efforts to limit greenhouse gas emissions are successful today.”

Cities are home to about 55 percent of the world’s population and generate about 80 percent of the planet’s gross domestic product, according to the report, and roughly 40 percent of the global population lives within just more than 60 miles of a coast.

Investors might believe the best approach is to “wait and see” whether climate change predictions come true, the authors note, but the most significant effects will likely be unpredictable in their timing and severity.

“Waiting may instead mean running out of time to prevent severe damages, especially if the pace of climate change accelerates,” the report states.

Some cities are already adapting to the changing climate, but the report states that “far more efforts are needed for cities to withstand the potential effects of a warming world.”

Many coastal cities will need to build seawalls and flood protection barriers to hold off rising seas and expand drainage systems to handle the excess water, according to the report. Electrical utilities will need to bury cables and bolster grids to deal with flooding and winds from increasingly strong storm. Bridges will need reinforcing, airports and railroads need fortifying.

All that work will take financing, and the report states that financing is likely to come from many sources.

“All cities will need to consider the hurdles associated with raising funding to support adaptation efforts. Even thriving cities will likely need to look beyond local tax revenues to central-government funding, public-private partnerships, institutional investors and international financial institutions, especially for projects in developing economies.”

Even if cities do begin to invest in preparing for the worst, what if the current projections are too conservative?

“For example, building a seawall to withstand today’s ‘worst-case’ 10-foot storm surge won’t be of much use if in two decades the surge turns out to be 15 feet. Considering that climate projections have been repeatedly revised to show increasingly severe outcomes, this is a real concern,” the authors note. “If climate change is worse than anticipated, even adaptive measures that seem prudent today may prove to be insufficient in the future.”

On human caused greenhouse gas emissions

“This trend toward a warmer world appears unlikely to abate in the near or even medium term. There are two key drivers of ongoing global warming. The first is net greenhouse gas emissions, principally of carbon dioxide (CO2). Such emissions would need to be cut dramatically in order to significantly curtail the trajectory of climate change, according to most climate scientists.”

“For context, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change1 (IPCC) indicates that limiting cumulative global warming to 1.5°C this century (the goal of the 2015 Paris Agreement) would require global CO2 emissions alone to decline by 45% between 2010 and 2030, and then to reach net zero by 2050. Limiting warming to the still-ambitious goal of 2.0°C this century would require CO2 emissions to decline by 25% between 2010 and 2030, and then to reach net zero by 2070.”

“Meeting these goals will likely be a challenge. In fact, after a temporary pause in the middle of this decade, global CO2 emissions are again on the rise and reached a new high in 2018.”

“The second reason to expect ongoing climate change is past greenhouse gas emissions. Even if current emissions were actually to reach net zero in the next few years, climate scientists indicate that emissions that are already in the atmosphere are likely to warm the earth for decades to come.”

Impacts on urban infrastructure:

“High temperatures can make road surfaces and rails buckle and can disrupt aviation by making some airports unusable. Winds and storms can cause power outages and destabilize bridges. Flooding can wash away rails and roads, destroy communications systems, overwhelm drainage systems and contaminate drinking water. Forest fires can disrupt economic activity and cause massive economic and personal losses.”

Other key findings in the report:

“Bearing in mind the many uncertainties about the timing, scope and magnitude of climate change, we note that the potential negative consequences could include:”

More frequent, more intense and longer-lasting heatwaves that harm human health, especially among vulnerable populations, reduce productivity, disrupt economic activity and hurt agriculture. According to the IPCC, it is “virtually certain” that there will be more frequent hot and fewer cold extreme temperature days, and it is “very likely” that heat waves will occur with higher frequency and longer duration, particularly in the tropics. Higher surface temperatures could exacerbate the warming process by causing permafrost to melt, releasing further methane and CO2 into the atmosphere.

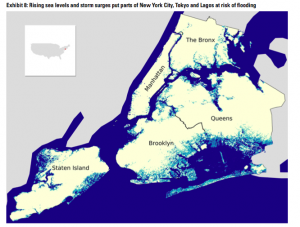

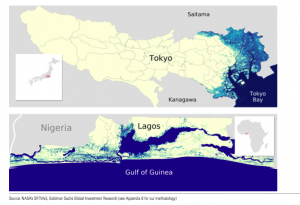

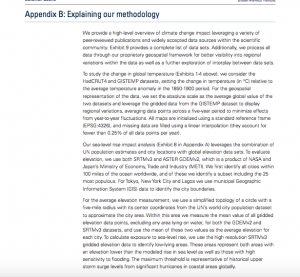

More frequent destructive weather events, including storms, winds, flooding and fires. Some regions could see more precipitation, and tropical cyclones bringing heavy rain and winds could become more frequent or more intense (or both). The maps below show (in shades of blue) our estimates of how flooding could affect some of the world’s major coastal cities, including New York, Tokyo and Lagos. Other major low-lying coastal or already flood-prone cities include Shanghai, Dhaka, Mumbai and Karachi – each of which has a population of 15 million people or more (see Exhibits 7 and 8 below and Appendix B for our methodology). Yet in other areas, droughts are projected to become more frequent and more intense.

Changing disease patterns, which could adversely affect human health. Warmer temperatures could cause disease vectors to migrate from the tropics to regions where people have less immunity; this is true not only for viruses like malaria and dengue fever but also for water-borne and food-borne diseases. Air pollution and increased ground-level ozone could also increase occurrences of asthma and respiratory diseases.

Shifting agricultural patterns, affecting the availability of food. Warmer temperatures and shifting precipitation patterns could reduce yields and nutritional quality as well change growing seasons and agricultural zones around the world. Livestock could be affected by higher temperatures and reduced water supplies. Ocean acidification is likely to put stress on aquatic populations and affect current fishing patterns. Some of these changes are already underway. Some climate scientists, for example, estimate that coral reefs will be all but extinct over the course of the century due to ocean acidification.

Pressure on the availability and quality of water, with widespread potential consequences. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that half of the world’s population will live in water-stressed areas as soon as 2025. Even in non-stressed areas, the quality of surface water could deteriorate as more rain and storms drive erosion and the release of toxins. These dynamics could affect everything from the availability of drinking water for people to a shortage of water for livestock and crops (with negative effects for the food supply) to decreases in hydroelectric power generation (which itself is expected to play a role in countering carbon accumulation over the long term).