An Alabama lawmaker, named in the documents of the late Republican gerrymandering expert, Thomas Hofeller, declined to say whether he recalls working with Hofeller during Alabama’s 2010 redistricting cycle.

An article published by The Intercept on Monday included documents and emails that seemed to show then-Alabama Rep. Jim McClendon, R-Springville, the House chair of the Joint Committee on Redistricting, worked with Hofeller to draw those redistricting lines, and that Hofeller sought to help Alabama Republicans to redraw lines based on race.

McClendon currently serves as a State Senator having moved to the upper chamber in 2014.

Judges have ruled the practice of racial gerrymandering, which packs minorities into some districts and spreads them out in others to limit their voting power, is unconstitutional under the 14th Amendment’s equal protection clause. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 also makes the practice of racial gerrymandering illegal.

McClendon, speaking to APR on Monday, declined to say whether he recalled working with Hofeller, and said he’d have no comments until after his attorney had read The Intercept story.

Hofeller’s files, included with David Daley’s story in The Intercept, show that he worked on the state’s redistricting maps well before any lines were drawn.

According to documents, Hofeller was involved in the editing of a document called “Reapportionment Committee Guidelines for Legislative, State Board of Education, and Congressional Redistricting State of Alabama” and worked on those edits with McClendon.

The Intercept’s story includes an email that the online news website states is from McClendon to Hofeller. The article states that McClendon sent and received emails from Hofeller at McClendon’s personal email account, and not his official state email.

Reached by phone Monday, McClendon at first declined to discuss the matter until he had read the article, but he called APR back 23 minutes later and prefaced the discussion by saying that “everything I say or do relating to redistricting shows up in court…it doesn’t matter if I’m out here fishing with my buddy and I make a comment about redistricting, it can show up in court, and it’s just, it’s part of the game.”

McClendon said he was chairman of the House redistricting committee in 2011, and “no matter how we, and in our case the Republicans were in the minority, had drawn the districts, the Democrats were going to sue. Back when they drew the districts we sued them. This time, we’re going to draw the districts again and they’re going to sue us.”

“Knowing that everything is going to show up in court, then you have to be very thoughtful about what you say. For that reason. I don’t say much,” McClendon said.

McClendon said that in 2011, the redistricting committee’s work was subject to prior approval by the U.S. Justice Department “for everything we did,” because at the time the state was still under the pre-clearances provision of the Voting Rights Act.

“So with that in mind, the strategy was very simple, and it was understood by everybody. It was pretty commonplace. We did this for congressional districts and we did this for House districts. We drew minority districts first. That’s how you guarantee they get to keep what they’ve got,” McClendon said.

Asked about the Hofeller’s documents in The Intercept story relating to his work in Alabama, which indicate Hofeller was dividing Alabama’s district lines based on race to benefit Republicans and dilute minority votes, McClendon said “Well, I’m not going to comment on that.”

McClendon said Alabama’s population is about 25 percent black, and “25 percent of our legislators are blacks. Are you getting the picture here? Yeah. So. Okay. What do you want?”

McClendon then asked to talk off the record, and APR cautioned him that there was no agreement to discuss anything off the record.

Asked if he recalls working with Hofeller on Alabama’s redistricting lines, McClendon said, “I think we’ll just decide if we’re going to resume this conversation after my attorney’s had a chance to read the article.”

Asked if he had any concerns or comments about the The Intercept’s article, McClendon said, “No comment.”

McClendon’s email address is redacted from the document supplied with the article, but it states it was sent by McClendon on April 1, 2011, to Hofeller with the subject line “Alabama AG 4.1.2011” with a document attached.

That document contains information about a meeting the two were to have on April 4, at 9:30 a.m. with the state Attorney General at the time, which would have been Luther Strange, although the email does not name Strange. The attached document states details about the meeting, which were to discuss the redistricting process.

“I will be in my office, Room 207, Alabama Statehouse, Room 207 by 9 a.m. if you want to come by there beforehand. We can walk over to AG’s from there, or you can go direct to his office on Washington Avenue,” McClendon wrote to Hofeller, according to the document.

In another email, The Intercept included with its story, Dorman Walker, a partner at the Birmingham law firm Balch & Bingham and an attorney for the Legislature’s reapportionment committee at the time, wrote to Hofeller, Hofeller’s business partner, Dale Oldham, and John Ryder, then-Republican National Committee general counsel and National Committee member. The email was also copied to McClendon.

According to The Intercept’s document, the email was sent on April 19, 2011, with the subject line “Confidential and Privileged Alabama Guidelines.”

The email states:

“Tom, Dale, and John,

Thanks to Tom for his good comments. Please see my further comments, in the first attachment, and my proposed changes, in response to what Tom has pointed out, in the second attachment.”

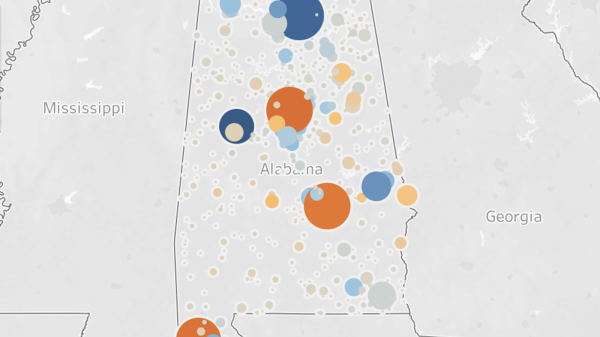

Another of Hofeller’s files in The Intercept story is titled “MINORITY DISTRICTS IN 2012 ALABAMA LEGISLATIVE REDISTRICTING” and lists the many redistricting plans at the time, breaking down proposed districts by the percentage of blacks and non-hispanic whites in each.

In January 2017, three federal judges ruled that maps redrawn by Alabama Republicans after the 2010 census were racially gerrymandered. The judges ruled that maps for 12 legislative districts, which were used in the 2014 election, could not be used again.

The discovery of Hofeller’s work in Alabama could have implications for another lawsuit in federal court, filed in June 2018, by eight Alabama voters who allege that the state’s 2011 congressional map was illegally gerrymandered to Republican’s favor. Oral arguments in the lawsuit are to begin November 4. Attempts to reach an attorney for the plaintiffs Monday afternoon were unsuccessful.

David Daley first wrote about Hofeller’s once-secret files for The New Yorker on Sept. 6. The files, kept on hard drives and thumb drives, surfaced after Hofeller’s death in August 2018, when his estranged daughter discovered them and gave them to attorneys working on a gerrymandering case in North Carolina.

A federal court ruled that congressional lines Hofeller helped draw in North Carolina in 2016, were unconstitutional racial gerrymandering. Some of Hofeller’s files on his work in North Carolina became part of that case, although the files on his work in Alabama remained undisclosed until Monday.

In June, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that partisan redistricting is beyond the reach of federal courts, leaving it up to states and the legislative branch to decide.

McClendon told APR in June that he was pleased with the court’s ruling.

“As Senate Chairman of Redistricting, I am pleased to have a clear ruling and receiving it in a timely manner,” McClendon said. “We have much work ahead of us, and their decision today on this issue will allow us to proceed. We will be receiving census data in early spring of 2021, and this court decision resolves many questions.”

According to The Washington Post, other Hofeller files indicate he helped President Donald Trump’s administration in an attempt to include a citizenship question to the 2020 census, arguing that it would be an electoral advantage for Republicans and “Non-Hispanic Whites.”

The Intercept story on Monday included files that showed Hofeller’s work to redraw lines based on race in Florida and West Virginia.