Editor’s note: This is the third installment in APR’s yearlong series on climate change in Alabama. Eddie Burkhalter is a staff writer at Alabama Political Reporter and a fellow at the Poynter-Koch Media and Journalism Fellowship. The program is a partnership between the Poynter Institute and the Charles Koch Institute. Charles G. Koch is chairman of the board of the Charles Koch Institute and CEO of the multinational petroleum company Koch Industries.

With summers getting hotter, more U.S. cities are seeing longer periods of stagnant air and worsening air quality, according to experts.

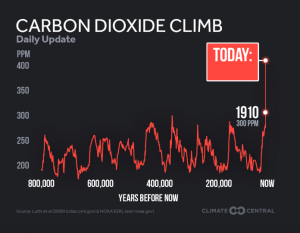

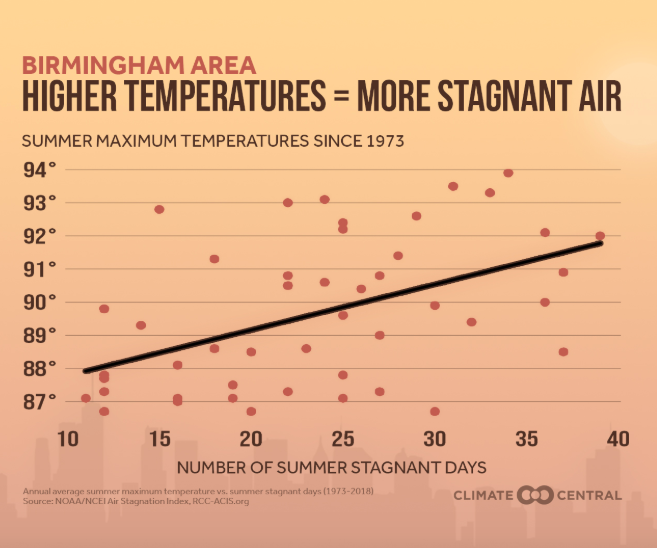

A study by the nonprofit news outlet Climate Central published July 24 compared the average summer maximum temperatures to the average number of stagnant days during the summer.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association’s air stagnation index uses upper atmospheric winds, surface winds and precipitation to calculate the daily level of stagnation, which can trap air pollutants over an area, worsening breathing problems.

Since NOAA began monitoring air stagnation in 1973 Birmingham’s number of stagnant summer days increased 254 percent, from 11 days annually to 39 days in 2018, according to the study. During that time the average annual summer maximum temperature in Birmingham rose from 87 degrees to 92 degrees.

“Since 1973, 98 percent of the cities analyzed show a positive correlation between summer high temperatures and the number of summer stagnant days,” according to the study.

As the climate continues to warm, stagnant days are projected to increase further, with up to 40 more days per year by late-century, according to a separate study by Stanford University published in 2014.

“Considering the strong links between air stagnation, air quality and public health impacts, our results suggest that continued increases in greenhouse gas concentrations are likely to alter the atmosphere in ways that impact efforts to protect public health,” the Stanford University study’s authors note.

Chandana Mitra, associate professor of geosciences at Auburn University, teaches on climatology and climate change.

“One of my areas of research is urban heat and how it impacts humans,” Mitra recently told APR by phone.

As we transform natural habitats into steel and concrete cityscapes, those areas absorb and emit more of the sun’s energy as heat, Mitra said.

“And heat is a very important component in any science equation, which can influence every single other component within that equation,” Mitra said.

Some of the heat absorbed by those steel and concrete cityscapes isn’t immediately emitted back into the atmosphere, Mitra said, but rather stored, which can cause “urban heat islands.” Those heat islands, coupled with prolonged heatwaves, can have deadly results, she said especially for the elderly, children and low-income residents with inadequate air-conditioning.

Record heat waves this year swept across Europe, South Asia and the Middle East. The United Kingdom’s national weather service Met Office on Monday announced that the UK saw its hottest day on record last Thursday. Belgium, the Netherlands and France all also say records highs last week.

At least 11 people in Japan died in Japan last week due to an unexpected heat wave, while another 5,6oo were sent to hospitals for treatment, according to the Kyodo new agency.

A heat wave blanketed a third of the population of the U.S. earlier in July, breaking one-day temperature records in numerous cities and causing at least six deaths in Maryland, Arizona and Arkansas according to news accounts.

According to NOAA extreme heat causes more deaths in the U.S. than hurricanes and floods combined, more than twice as as tornadoes and four times as many as from extreme cold.

Mitra said the cause of the increasing global temperatures and longer and stronger heat waves is global warming, and that it needs to be addressed quickly.

“This is something very unprecedented and we’re not prepared to deal with it,” Mitra said.

Jennifer Francis, senior scientist at the Woods Hole Research Center in Massachusetts, is a world-renowned expert on arctic climate change impacts.

“Of course, heatwaves are nothing new, but recent studies suggest they’re getting hotter and lasting longer,” Francis wrote in an email to APR on Wednesday.

Francis said new findings show that the persistence of heatwaves and other events such as droughts and prolonged rains are the result of so-called blocking events and large northward swings in the jet stream called ridges.

“Blocks occur when the jet stream takes such a large and sharp northward bulge that a big swirl breaks off in the upper levels, just like an eddy in a river,” Francis said.

Once those blocks form they tend to stick around for days or weeks, preventing weather systems east and west of them from moving, she said.

A block currently parked over Greenland is keeping weather patterns across North America from moving eastward, Francis said, including the big ridge over the western two-thirds of the US.

“This pattern is causing the persistent high-pressure area that tends to trap pollution near the surface and deteriorate air quality,” Francis said.

Asked if we can expect our summers to continue getting hotter, and heat waves to continue on for longer periods, Francis said yes.

“Unless we can find a way to drastically reduce our emissions of greenhouse gases. The extra heat trapped by these gases — that come mostly from burning coal, oil and gas — is the underlying cause of these stronger heatwaves,” Francis said. “Any reduction in our emissions will slow their intensification, but we need to act boldly and soon.”