Most Alabamians may not realize it, but one of the world’s newest and most unique beach walks is right here in their own state. Seashells and driftwood on a white sand beach, soft breezes, waves crashing, seagulls calling, pelicans and ospreys circling and diving, dolphins chasing schools of mullet in shallow water and some of the most stunning ocean sunrises and sunsets in the world happen every day along Pelican Peninsula.

That’s what locals now call the sandy spit which extends a mile south of Dauphin Island. And Pelican Peninsula is not just a great nature walk but also a walk back in history and a chance to look at geology happening right before your very eyes.

Pelican Peninsula is a relatively undiscovered beach walk because it is new — so new, in fact, that it is not on any maps. Indeed, it didn’t exist a decade ago and will probably be gone in the next decade or so. It is part of a unique geologic phenomenon, which only happens at that spot, and only once every 150 years or so. It is happening now and creating the opportunity to walk from an inhabited barrier island out toward the sea on an uninhabited barrier island.

Pelican Peninsula is not on any maps because 10 years ago, it was Pelican Island. The little island/sand bar, with its sea oats and tidal flats, has moved around for centuries in this same general location, frequently overtopped by hurricanes and often cut into multiple pieces. But in 2008, Pelican Island moved so far north that it sealed off Pelican Passage, the former channel between Pelican Island and Dauphin Island. It has now migrated, or welded, onto the much larger Dauphin Island.

Like Halley’s Comet, this is an infrequent phenomenon, but it is even rarer than the comet because it happens only once every 150 years, twice the span between Halley’s. So your grandfather probably could not have seen this, but his great-grandfather could have.

Twice in recorded history, Pelican Island has attached like this to Dauphin Island. It happened in 1852 and before that in the early 1700s, when Pelican Passage was open and used as the entrance to a harbor on the south side of Isle Dauphine. What is now called Pelican Island, referred to as Isle a l’Espagnol on one old map, functioned as a breakwater for the harbor, as did a smaller sand spit peninsula, which extended from Dauphin Island. (There is a very similar, smaller sand spit there today that I call Sanchez Spit for the south Mobile County native and direct descendant of Jean Baptiste Baudreau dit Graveline, who first showed me the remarkable similarity between this newly formed spit and its geomorphological ancestor.)

I have walked Pelican Peninsula several times the past few years, and it is always changing. Every storm changes it. In fact, the walk keeps getting shorter every year. Last year’s Hurricane Michael knocked about a quarter of a mile off the southern end of the peninsula, and it is destined to get shorter and shorter as the sand migrates north onto the beaches of Dauphin Island. Within a few decades, it will just be a very wide beach with sand dunes.

From the perspective of the eroded beaches of Dauphin Island, this geologic phenomenon is good. It is a huge, natural, very-slow beach nourishment project. Millions of cubic yards of sand will be driven north to the beaches of Dauphin Island by waves over the next decade or so. Already, the beach at the island Park & Beach Board’s former fishing pier is several hundred yards wider than just a decade ago. The former fishing pier is now completely sanded in and is the longest beach boardwalk in the state.

Newly built steps down to the beach at the south end of the former fishing pier make for the perfect start for your beach walk. If you’re interested in taking one of the great beach strolls in the world, drive to Dauphin Island, park in the public Park & Beach Board parking lot, head out on the former fishing pier and then go as far as you like on Pelican Peninsula.

Today, the peninsula is about a mile long now. Next year, it probably will be shorter. So don’t wait too long, and remember: This will never happen again in your or your children’s lifetimes.

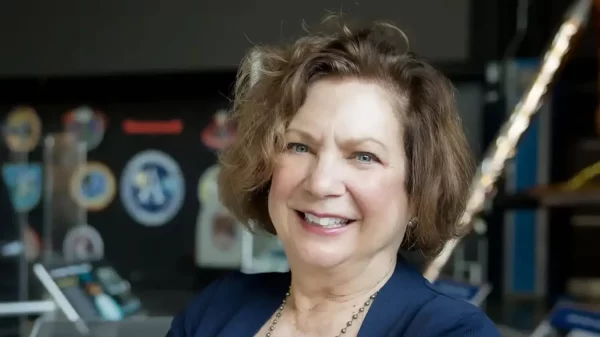

Dr. Scott L. Douglass is a professor of civil engineering at the University of South Alabama who has taught coastal geomorphology at the Dauphin Island Sea Lab for 20 years. He is the author of the book “Saving America’s Beaches: The Causes of and Solutions to Beach Erosion” and has visited more than 500 beaches in the United States and around the world. He is president of South Coast Engineers in Fairhope.