A robotic voice that reads long bills at length in the Alabama Legislature might have one less job if one lawmaker has anything to say about it.

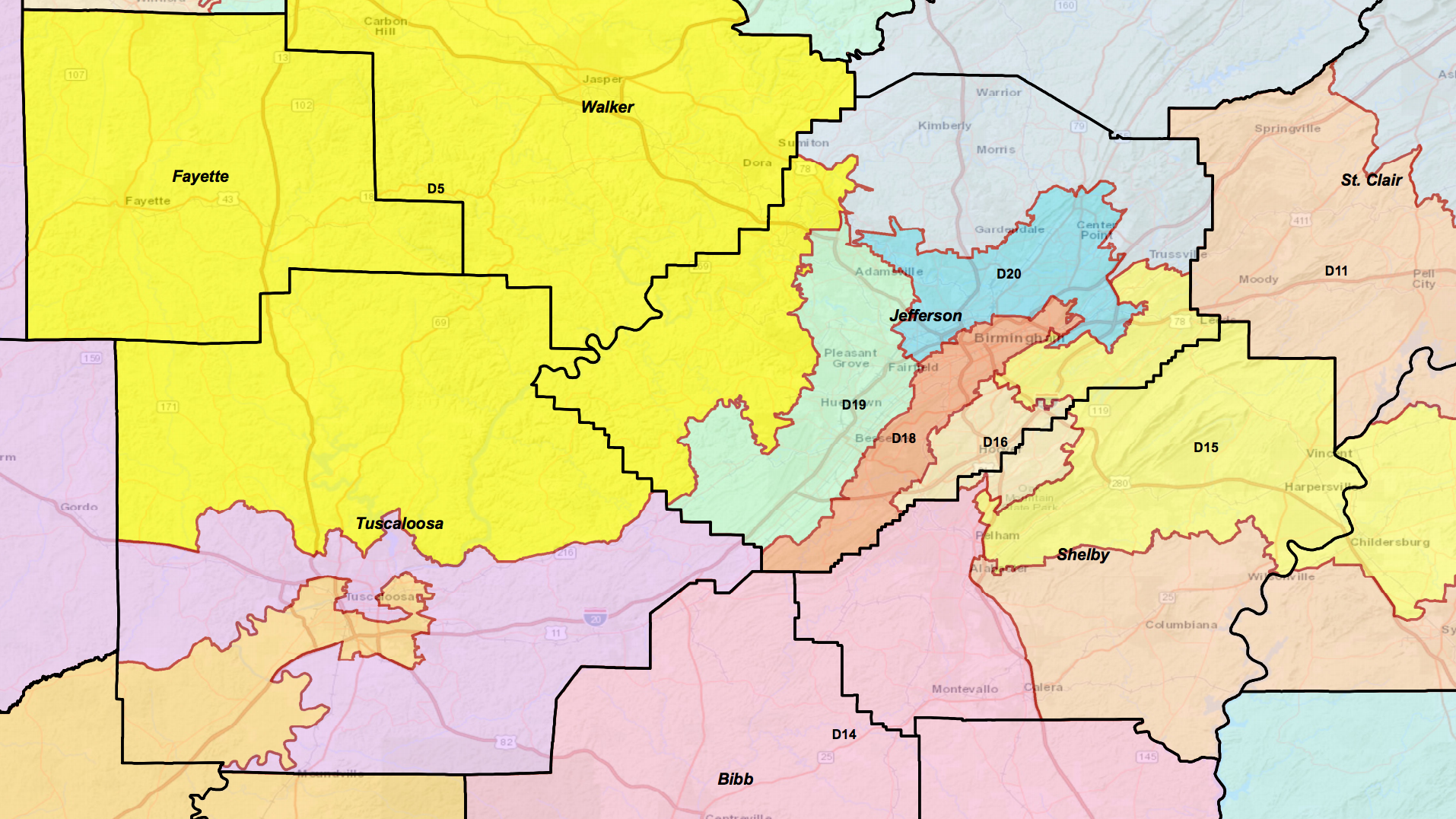

When lawmakers were working to approve redrawn legislative districts in 2017 after a federal court ruled them unconstitutional, the robotic voice echoed through the halls of the Alabama Statehouse for nearly 16 hours.

The bill to shift about 70 House districts was being read at length at the call of Democratic lawmakers hoping to delay its approval.

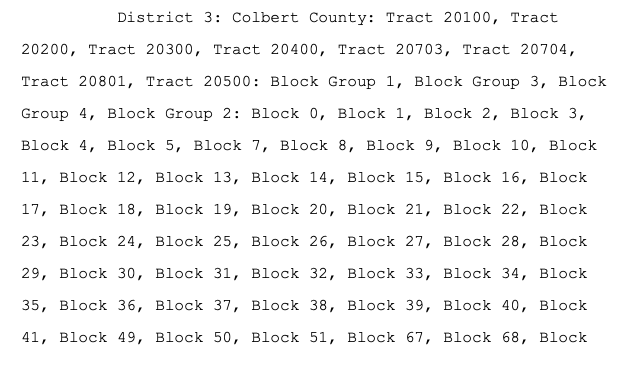

The robotic machine chugged along, reading the 580-page bill and its more than 80,000 blocks and tracts until the GOP-held House passed the redistricting measure by a vote of 70-30.

A section from the 580-page 2017 House reapportionment bill, which was read at length for nearly 16 hours.

“The machines are reading in this drone of a voice,” said Sen. Jim McClendon, R-Springville, who is sponsoring a constitutional amendment that would do away with redistricting bills being read at length.

“You can listen to it, and even if you pay attention to it, you can’t make any sense out of it,” McClendon said. “You have no clue what they’re talking about.”

No other legislation could move while the full bill was read. Things stalled. But no one could go home for a nap. The lawmaker who requested the reading could withdraw their request and a vote would immediately follow.

The process in the House — where debate in 2017 was most contentious — ended up eating almost two legislative days as the 2017 legislative session neared its end.

Republicans were irritated with the Democrats’ tactics, but the minority felt they had no other option after the majority voted to cloture debate.

“If you were in that situation and did not have a voice, you would use every tool you had to try to get your message out,” Rep. Mary Moore, D-Birmingham, said at the time. “We used the tools we had to try to get the message out.”

The bill redrawing Senate districts killed nearly a full legislative day in that chamber, too. It also ended up passing. The courts later upheld the redrawn districts after forcing lawmakers to make new maps following a ruling that the original districts, drawn by GOP lawmakers in 2011, were improperly based upon race.

Three of the districts were Senate districts and nine were in the House.

With less than two years until lawmakers will again be in the position of redrawing Alabama’s legislative and congressional districts after the 2020 census, one lawmaker is already looking ahead.

McClendon, has introduced a constitutional amendment to end the practice of bills being read at length.

As things stand now, no vote is needed to initiate the reading process. If a lawmaker requests it prior to a vote, the electronic reading machine is turned on.

But the reality is that the process is enumerated in Alabama’s Constitution, and it’s been that way for decades.

“I’m sure it was a practical request in 1901,” McClendon said. “They didn’t have copy machines. They probably computers or laptops. I would imagine there were some legislators who made it to Montgomery who weren’t that accomplished at the written word anyway. But it’s not a good idea now.”

Democrats regularly use the procedural tactic to delay votes on all sorts of bills, but reading at length is most effective — and most time-consuming — with reapportionment bills, which typically run hundreds of pages.

“The only reason in the modern world to have a bill to be read at length would be to extract some kind of punishment on the people who are supporting the bill,” McClendon said. “Because it does not change the outcome at all.”

A reading of a full-length House district reapportionment bill could take upward of 25 hours, McClendon said. A full Senate bill could take between 12 and 14 hours.

“The outcome is not affected by reading the bill at length, and it does not enlighten anyone as to the content of the bill,” McClendon said.

McClendon’s bill would only affect reapportionment legislation.

“I wanted to do a bill that would include all reading at length but I thought I would just focus on this one issue and maybe someone else can come up with another one to get rid of all reading at length,” McClendon said.

Reapportionment, though often considered a boring subject to the public and legislators alike, is one of the most important acts of the Legislature. They not only decide state school board and state legislative districts, but they also decide the alignment of the state’s congressional districts.

The Black Caucus, who challenged the 2011 lines in the lawsuit, successfully argued in Federal court that the GOP packed black voters, who often support Democrats, into a handful of districts to limit the Democrats’ power.

Democrats, who were largely concerned about House districts in Jefferson County, felt they weren’t given enough say in the process of redrawing the 12 legislative districts found to be gerrymandered, so they resorted to reading at length.

“It’s not fun sitting in here reading where you’re not being productive,” Rep. John Knight, D-Montgomery, said at the time. “We’d rather be productive, but the only thing we were asking for is fairness. You have just a few people from one little area basically tie up this whole Legislature. So you might as well not have representation from across this state.”

McClendon said in an interview with APR that he understands concerns about minority influence, but that reading at length never changes the outcome.

“It’s not much of a tool if it doesn’t fix anything or change anything. It’s just a delay tactic,” McClendon said. “If it were taking away something useful from the minority in expressing their position on something or getting something done, I would feel different about it. I don’t want to do that.”

The reality, though, is that the move does give the minority some leverage, especially at the end of the legislative session when the session has a time limit and other unrelated bills may still need attention.

The next U.S. Census will be held in 2020. The Legislature will receive data for reapportionment in the early part of 2021, and it will need to redraw the lines by election time in 2022.

The process could be even more contentious in 2021 if Alabama were to lose a congressional seat. If lawmakers have to draw out one of the state’s seven congressional districts, a serious battle could ensue.

If McClendon’s bill makes it out of committee to the floor, it would require approval by both chambers. At that point, it would be put on the 2020 primary ballot. Voters would be able to decide whether or not to end the practice.