Majority-white public schools received about $23 billion more in funding than majority-nonwhite schools in 2016, according to a report from the nonprofit group EdBuild.

That seemed to surprise a lot of people when the study’s findings were reported in the Washington Post last week. I’m not sure why.

The majority of school funding models are based on property tax revenues, and the majority of affluent landowners in this country are white. We made sure of that for decades in the post-slavery America, utilizing a variety of tactics and Jim Crow laws to ensure that blacks and other minorities knew their place.

In Alabama, we took it a step further. Because if we’re going to overachieve at anything, you can bet it’ll be racism or football.

In this state, to ensure that wealthy landowners didn’t accidentally pay to properly educate black children, we set up a property tax system that taxed working land at much lower rates. Places like plantations and timber land and large farms often didn’t pay as much in taxes as the standard, single-family home.

It’s a system that mostly remains intact today, which explains a lot about the sad state of our education funding.

Because we’re all on this planet together, though, and because you can’t inflict hatred and misery on one group of people without it affecting everyone, this tactic has harmed us all in myriad ways. It has deprived us of countless geniuses, who happened to have darker skin, and it has helped racism thrive.

But it has also done something else: It has instilled a level of disinterest in nonwhite people, even nonwhite heroes, in our education system and ultimately in our lives. It has led us to approach their struggles and triumphs with a shocking level of indifference.

This is why movies like “Green Book,” which won the Academy Award for Best Picture last Sunday, receive such fanfare. We don’t understand what we don’t understand.

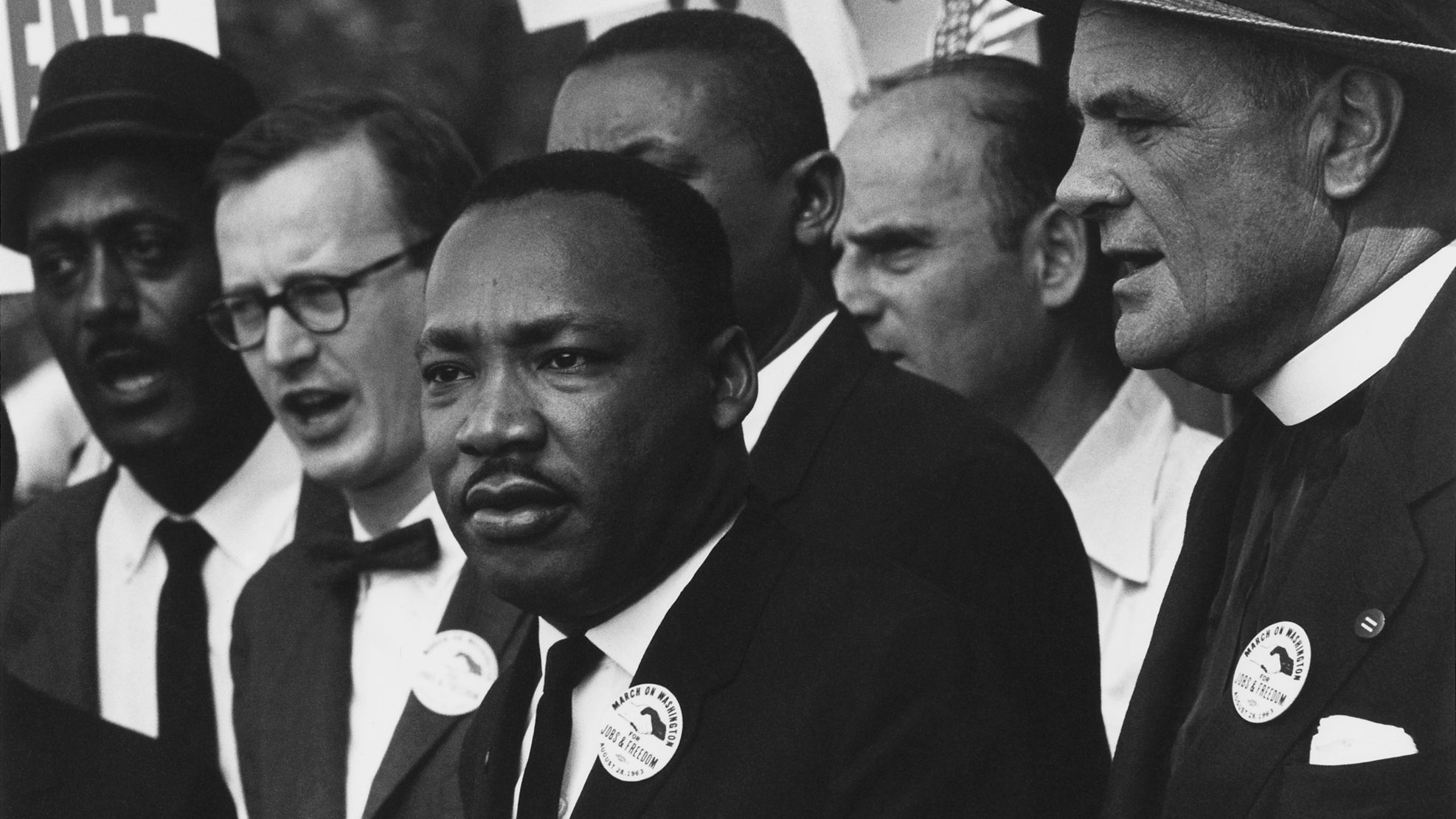

We’ve turned the fight for civil rights in this country into a comic book war, and we’ve turned the people who fought those battles into caricatures and cartoons. We’ve totally transformed the environments in which they lived and survived and fought into these made-for-Hollywood, weepy scenes in which only the clearly evil failed to recognize the unflawed minority hero.

Growing up in Alabama public schools, I entered adulthood believing that Martin Luther King Jr. was something just short of a saint, who was loved by all — black and white — and that racism died because a tired seamstress didn’t want to move out of the white section on the bus one day.

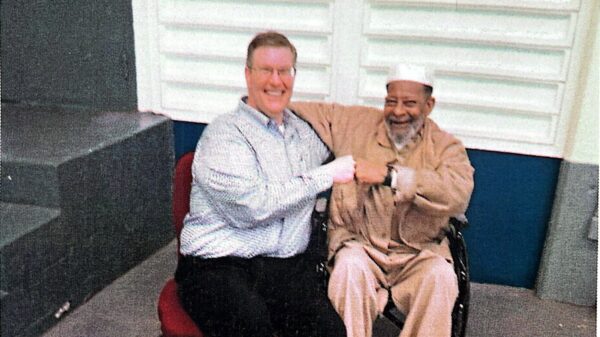

It wasn’t until I met attorney Fred Gray in the early 2000s that I discovered just how utterly misled I had been. Because I had zero idea who Fred Gray was.

“You should look me up,” Gray told me one day. I did.

Let me tell you all you need to know about Gray’s lawyering skills: In the mid-1960s, in the height of the Civil Rights Movement, MLK was prosecuted for tax evasion. Fred Gray got him acquitted. In Alabama. By an all-white jury.

Sell that damn movie.

He also defended Rosa Parks in the Montgomery bus desegregation case, won approval for the Selma-to-Montgomery march, desegregated Alabama’s public colleges, helped plan the bus boycott and brought national attention to the horror that was the Tuskegee syphilis experiment.

I remember thinking: How is this stuff not in textbooks?

And it just kept getting worse.

Turns out, Rosa Parks wasn’t just some timid and tired seamstress. She was a legit superhero who fought off a would-be rapist and then went to work trying to expose and bring to justice men who sexually assaulted black women in the days of Jim Crow.

She knew she had almost zero chance of winning convictions from all-white juries, but that never stopped her from shaming men publicly — through the media, through government officials, through simple word of mouth.

She and Gray and their team of “agitators” helped plan and pull off the Montgomery Bus Boycott. And they didn’t do it by luck or by the goodwill of a white savior who rode in to push the well-meaning-but-downtrodden blacks over the finish line.

They did it with intelligence and cunning and planning and bravery.

It’s an awful travesty that American school kids don’t know the names of E.D. Nixon, Claudette Colvin, Jo Ann Robinson and so many others.

But then, knowing these men and women, and knowing their full stories and the history that has truly shaped us all, would lead to a better understanding and possibly a bit more harmony.

And denying that outcome seems to be the point of it all.