A report from the University of Alabama’s Alabama Transportation Institute and Alabama Transportation Policy Research Center found that the state needs to invest between $600 million and $800 million annually for the next 20 years to meet infrastructure needs.

The report — “Addressing Alabama’s Transporation Infrastructure: Roads and Bridges” — found that Alabama needs to make major investments to simply maintain current infrastructure needs and even more if it wants to be competitive in the years to come.

The UA report comes as the Legislature is set to consider a gasoline tax increase this year as a method of funding infrastructure investment. The gas tax hasn’t been increased or adjusted for inflation since 1992.

The GOP leadership in both chambers of the state Legislature have so far been unified in their calls for a moderate gas tax increase. Gov. Kay Ivey has also endorsed the plan.

Researchers at ATI developed seven different scenarios set in the year 2040 to determine the needed investments in infrastructure. The scenarios range from continuing current practices to pursuing an optimal path that considers needs of different regions across the state.

The scenarios range from maintaining 2016 urban congestion levels to creating congestion levels that ensure Alabama cities are economically competitive or that the state reaches the best achievable congestion conditions.

“The Alabama economy depends on a functioning network of roads and bridges,” said Shashi Nambisan, the executive director of the Alabama Transportation Institute. “Today, we have increasing population meeting aging infrastructure, congestion, safety concerns and stagnant funding. This puts elected officials and decision makers in a difficult position. We’ve put together some options for a path forward.”

The most basic scenario would cost $12 billion over the next 20 years or $600 million a year. The optimum scenario would cost $16 billion over the next 20 years or $800 million a year.

“We were asked to document conditions now and in 2040 to support decision makers across the state,” Nambisan said. “We have estimated the funding needed to address various scenarios. We are not advocating for any particular method of meeting those needs financially.”

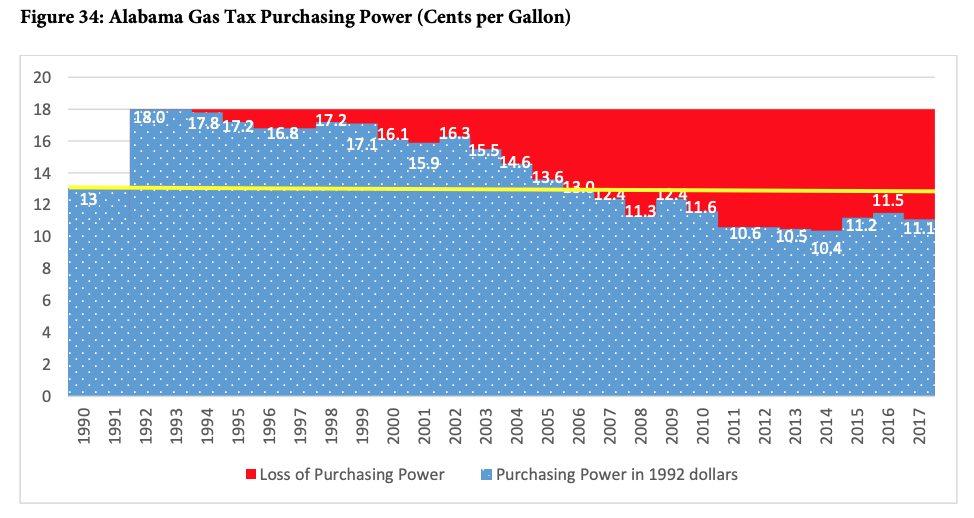

Alabama’s gas tax revenues have lost and continue to lose purchasing power because of inflation. Increasing fuel efficiency, fleet changes and electric vehicles are also cutting into gasoline and diesel tax revenues.

The changes have been so significant that any purchasing power gained from the last fuel tax increase of a nickel per gallon in 1992 has been negated.

Alabama’s gas tax revenues have lost and continue to lose purchasing power because of inflation.

Researchers looked at the possibility of using an inflation index to increase the revenue generated by the motor fuels tax. If Alabama had implemented indexing to the Consumer Price Index — a widely used measure of inflation — then the an additional $5.3 billion could have been raised since 1992.

If the tax rate had been indexed, the state motor fuels tax would be 31 cents per gallon of gasoline today instead of 18 cents per gallon of gasoline, the researchers found.

“We have developed a network of roads and bridges that has served us well, but the purchasing power of transportation funding has eroded over time,” Nambisan said. “For us to sustain the quality of lives of Alabamians and maintain economic competitiveness with Southeastern states, we must find ways to invest not only to maintain our transportation system, but to enhance it as well.”

The discussion comes at a time when Alabama’s infrastructure remains in somewhat dire conditions. If no investments are made, things could get significantly worse.

“Taxpayers and decision-makers should consider how they wish to pay for transportation costs,” the report said. “The taxes and fees represent one cost, but the extra travel time, wasted fuel in stop-and-go conditions added vehicle maintenance and operating costs, and missed meeting and family gathering time also have some cost implication.”

The annual costs of delays range from $240 per commuter in 2014 to $890 per commuter in the Birmingham-metro area. The average across the state’s metros is $450 per year per commuter, and the annual cost of delay to Alabama consumers is $1.4 billion, with an economic impact of $2.3 billion.

Some 8 percent of bridges in the state are structurally deficient. Nearly half of the bridges are over 50 years old. Typical bridges are designed only to have a lifespan of 50 to 70 years.

At the same time, about 20 percent of the state’s roads are in “marginal” condition, the lowest rating. At the same time, congestion is worsening as new roads aren’t being built to keep up with new traffic, population growth and the number of miles traveled.

From 1990 to 2015, the number of lane-miles increased only 14 percent while the state’s population has increased by 20 percent, registered vehicles increased 46 percent and vehicle miles traveled increased by 57 percent.

The number of recorded crashes has increased significantly in the past six years. The number jumped from a 20-year low of about 125,000 crashes in 2009 to nearly 155,000 in 2016. In 2016, traffic crashes across the state resulted in about 1,100 deaths — a 27 percent increase over 2015 numbers.

The economic losses caused by crashes has exceeded $15 billion every year since 2014 and continues to increase. In 2016, the number is estimated to be in excess of $18 billion.

“There is a cost associated with doing nothing,” said Steven Polunsky, the director of the Alabama Transportation Policy Research Center at UA and contributor to the report. “We’ll pay for it in weakened economic competitiveness, diminished economic productivity, increased vehicle maintenance and operating costs and impaired access to education, employment, healthcare and social-recreational opportunities.”