There is a process in place to approve charter schools in Alabama.

When the Alabama Legislature passed the law allowing charters in the state, they spent some time putting together a written plan with steps that must be followed. Things like: any organization wishing to start a charter school must submit an application that includes a detailed plan with specifics about funding and student-teacher ratios and facilities.

That plan must be approved by the state’s charter school board, or by a local school board that has applied and received approval from the Alabama State Department of Education to become a charter school authorizer.

But before any plan can be approved, it must first be submitted to the National Association of Charter School Authorizers, to which the state pays an annual fee to have all charter applications reviewed. The NACSA then makes a recommendation to the state’s charter school board or the local school board authorizers.

This is Alabama’s process for approving charter schools.

And somehow, Montgomery continues to get charter schools approved without following it.

Last year, LEAD Academy became the city’s first-ever charter school, despite failing to satisfy any of NACSA’s criteria and failing to receive its recommendation. LEAD also failed to receive a majority of the state charter board’s vote — a fact that has left it in limbo after the Alabama Education Association filed a lawsuit and a Montgomery Circuit Court judge blocked its approval.

And now, the approval of four conversion charters has been pushed through, despite that plan also failing to meet NACSA’s approval and despite the Montgomery County School Board failing to vote for the charters’ approval.

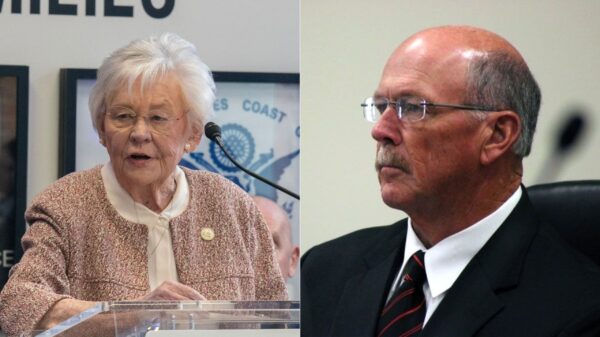

“The (Alabama State Department of Education) is pulling another fast one to get this approved,” said former MPS Board member Larry Lee, who began raising questions last year about the way the conversion charters were approved. “Simply put, the state is forcing this conversion charter (plan) on MPS.”

Lee and two other MPS board members, along with multiple MPS employees, spoke to APR about the process that will apparently turn four MPS traditional schools into conversion charters starting in the 2019-2020 school year. The MPS employees spoke on condition of anonymity out of fear of losing their jobs or being demoted.

For most of the employees and board members, the problem isn’t the introduction of charter schools into the system. For a system struggling in pretty much every area, all solutions are welcome. The teachers and principals who spoke to me are so desperate, in fact, that despite their reservations over the manner in which the conversion charters were approved, they’re clinging to hope that they bring some changes and help.

But they also worry that the flawed process will result in unqualified leadership operating inadequate schools that fail children and ultimately do more harm than good.

“The process is in place for a reason, and it never ends well when the process is ignored,” said one MPS principal. “Charters could make a real difference in this city if done right.”

That hasn’t been the case so far.

The four conversion charters will be operated by the Montgomery Education Foundation. To date, the MPS board members said, the Foundation has not presented the board with a plan for approval.

Under the current charter schools law, that’s an important step, since the Department of Education considers the MPS board an official charter school authorizer.

However, MPS board members dispute that point — that they are a charter school authorizer. They say that the board originally voted to become an authorizer, and even submitted paperwork to the state officially requesting to be an authorizer.

But their application was rejected by the state and sent back to MPS to work on. The primary issue, according to the board members and people within MPS who worked on the application, was funding — the system lacked the financial resources to set up and operate an office devoted to authorizing charters.

The MPS application also received an unfavorable review from NACSA.

At that point, after learning the full scope of what was expected out of an authorizer, the MPS board decided to drop the matter altogether.

“The MPS board figured out what all was involved in being an authorizer — for instance, you have to solicit charters to come to your system — and decided not to complete its application,” Lee said.

The board members insist that’s where they stopped with the process.

ALSDE, however, takes another view. According to Michael Sibley, the department’s director of communications, MPS’ original application “was never denied.” Instead, it was “left in pending status.”

And although the MPS board never addressed any of the concerns raised by NACSA, last January, “(interim superintendent Ed Richardson) removed the pending status,” Sibley said.

“This is a lawsuit waiting to happen,” said an MPS employee. “There’s no way he has the authority to both approve the board as a charter authorizer and then approve four conversion charters using that authority.”

Because that’s apparently what Richardson did. The Montgomery Education Foundation never submitted plans for conversion charters to the MPS board, despite the board being the only entity that could approve those charters in Montgomery.

“Basically, this is more flim-flamming of the process to rush in charters,” Lee said.