At the most recent Legislative Contract Review hearing, Alabama Department of Corrections Commissioner Jeff Dunn revealed that the state is planning to build three mega-style prisons at a cost of approximately $1 billion.

Less than two years ago, the Legislature rejected a plan by then-Gov. Robert Bentley to spend approximately $850 million on four new so-called mega-prisons. Dunn appeared before the review committee to secure approval of an extension to a contract with Birmingham-based Hoar Program Management, LLC, to complete a study that would result in a request for proposal to build the three facilities. The taxpayer outlay for Hoar’s work will total nearly $11.5 million.

The Contract Review Committee did not immediately approve the expenditure but has no authority to stop the project beyond 45 days.

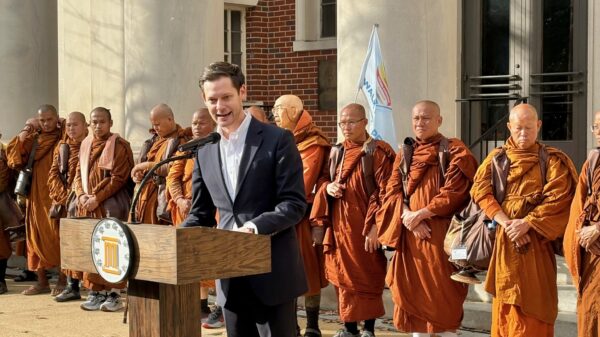

Until Dunn’s revelations at the recent contract review meeting, Gov. Kay Ivey’s administration has been quiet about any plans to build new prisons.

In the same week Dunn spoke about needing a billion dollars for new prisons, Ivey informed in-coming lawmakers that raising a fuel tax to pay for infrastructure projects would be her top priority in the 2019 Legislative Session.

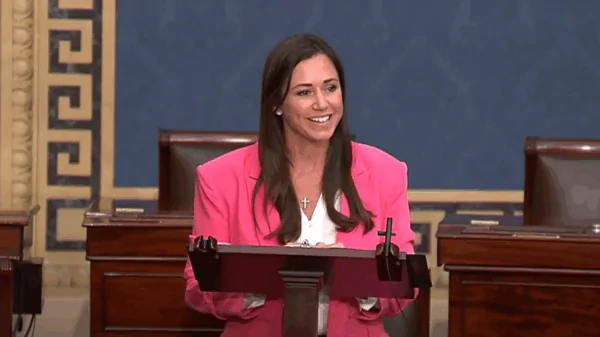

When Bentley pushed for four prisons in 2017, the project nearly passed the Legislature, but it is unknown how the Republican super-majority will react to two large projects in one Legislative session.

The Alabama Department of Corrections originally opened bidding in November 2017 for the contract to hire a team to oversee a comprehensive plan to improve the state’s corrections infrastructure. That was just months after the Bentley-backed plan died in the final days of the legislative session.

The plan was shot down two years in a row during the 2016 and 2017 legislative sessions. In 2017, a toned-down version of the plan passed in the Senate but died in the House in the final days of the legislative session.

The death of the prison bill was largely the result of splits between moderate and conservative GOP lawmakers who disagreed over the size of and methods within the plan, which would have authorized three new 4,000-bed regional men’s facilities and a 1,200-bed women’s facility at a cost of about $875 million.

The bill would have authorized a non-tradition design-build bidding process and a $1 billion bond issue, both of which drew the ire of conservatives who had worries about the cost and the bidding process.

Under Bentley’s original plan authorized by the Alabama Prison Transformation Initiative Act (APTI), the almost one billion dollars needed would have been borrowed off the books and controlled by a small group of individuals as part of a government corporation.

Most of the state’s existing facilities would have been shut down once the new prisons were built.

Under Section 14-2-6, the Alabama Corrections Institution Finance Authority governs the financial aspects of the state’s prison system. The Code of Alabama allows the authority to create a public corporation that has the power to issue bonds to build prisons and then lease the prisons it owns to the authority. The public corporation consists of the governor, the commissioner of corrections, the director of finance, the lieutenant governor and the attorney general as determined by Code of Alabama Section 14-2-2 through Section 14-2-6.

Under Section 14-2-6, the board of the authority consists of three members: the governor, who serves as the president of the authority; the ADOC commission, who serves as vice-president; and the director of finance as secretary.

It is unclear how Ivey plans to structure funding for three mega-prisons.

During the contract review meeting, Dunn secured a contract extension for architectural firms Goodwyn Mills & Cawood and the Seay Seay & Litchfield. Seay Seay & Litchfield does not list a specific amount, but Goodwyn Mills & Cawood is being paid $1.95 million for its services.

“ADOC’s approach is to have engineering and architectural services on contract in the event that a need arises,” said Alabama Department of Corrections Public Information Manager Bob Horton. “There are remaining funds on the SS&L contract for anticipated projects, so this is a no cost, time extension contract.”

Horton said the amendment to the Hoar Program Management contract, “will provide needed funding for the Alabama Prison Project Management Team, led by HPM, to continue the development of a comprehensive, long-range prison infrastructure revitalization plan.”

The plan floated in previous years — conceived by ADOC Commissioner Jeff Dunn, pushed by then-Gov. Robert Bentley and sponsored by Sen. Cam Ward in the Senate — was an effort to reduce severe overcrowding in Alabama’s prisons, which has been verging on 200 percent capacity. The severe overcrowding has been declining in recent years after a number of sentencing reform bills went into effect.

But ADOC officials and the plan’s supporters have said new facilities are needed to expand capacity and improve conditions as overcrowding has proven persistent despite the sentencing reform.

Those issues — combined with worsening dilapidation of prisons that were built largely in the 1960s and 1970s, though some opened as long ago as 1939 — have resulted in numerous lawsuits and calls for improvement to the state’s prison infrastructure. Needed maintenance is estimated at $440 million.

Since taking office, Ivey has backed away from Bentley’s plan, though she did consider a special session her first year in office to address the prison construction bill after it failed in the regular Legislative session in 2017.

In her first State of the State Address, Ivey called for more modest methods of improving Alabama’s prisons. Compared to Bentley’s $1 billion, bond-funded plan, Ivey’s proposal, which ended up passing the Legislature last year, moved away from a complete overall of the prison system. Instead, the Legislature allocated a $30 million supplement to the Department of Corrections’ funding for last fiscal year — an increase legislators said at the time was needed to comply with the court decision that mandated changes to medical and mental health care in Alabam’s prisons.

ADOC received more than a 20 percent increase to its budget this year, with the $30 million in additional emergency funding to ADOC’s budget last fiscal year combined with this year’s General Fund allocations.

The new talks of a prison construction plan come as ADOC is struggling to comply with a federal court ruling last year that found Alabama’s prison mental health care to be “horrendously inadequate.” That ruling was the second phase of a three-part lawsuit. The third phase, which challenges medical and dental care in Alabama prisons, has yet to be heard.