Throughout the 2018 election cycle, as major donors and top political action committees dumped needed cash into the campaign accounts of their chosen politicians, there was one major player in the state that remained remarkably quiet.

The Poarch Band of Creek Indians.

While PCI dumped buckets of cash into various PACs, it did so mostly without a clear objective and without making it known, in most cases, where the cash was destined to land.

And early on, PCI leaders made it clear that the tribe planned to lay back in this election and offer only modest support to longtime political allies.

That seems like an odd position to take during an election cycle that saw so many legislative seats up for grabs and important statewide races for governor and attorney general — two offices that have historically mattered a great deal to PCI’s economic success — on the ballot.

But the tribe’s silence was likely calculated. And for good reason.

The next couple of years could be perilous times for Alabama’s only federally recognized tribe, and as PCI leaders look to secure its future, this was no time to make enemies. Or to remind everyone that you’re running a statewide monopoly and raking in more than a billion dollars annually in untaxed profit.

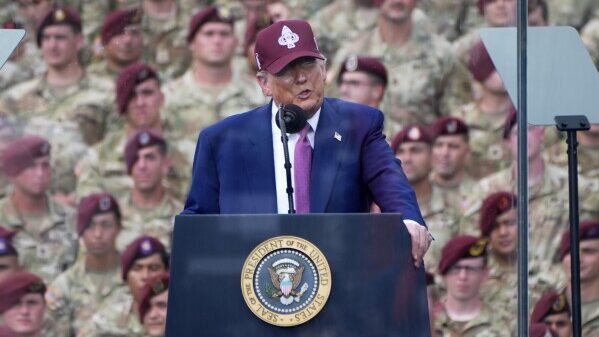

To understand why the Poarch Creeks — and many other tribes across the country — suddenly find themselves in such a dangerous position, you need just two words: Donald Trump.

Trump has long been viewed as hostile to Native American tribes, believing that they held an unfair advantage in opening and operating casinos. (Forget, of course, the long, awful history of this country’s mistreatment of the tribes, and the injustices that literally led to their people starving.)

And it should be no surprise that his administration has been astonishingly hostile when dealing with tribes — to the point of being borderline criminal in their behavior.

To illustrate this — and to underscore this new, perilous world that PCI now finds itself in — there are a couple of examples in the Northeast.

Most ominous is a decision in late September by the new head of the federal Bureau of Indian Affairs to remove a recognized tribe’s land from federal trust. Holding lands in trust is the manner in which Native American tribes protect their sovereignty and is a required step for the U.S. government to formally recognize a tribe’s sovereignty.

It has been decades — possibly as far back as the 1950s — since a tribe has had its land removed from trust, and most lawmakers and tribal leaders believed those days were in the past. But a 2009 U.S. Supreme Court decision, Carcieri v. Salazaar, which established that only tribes that were recognized in 1934 could benefit from the federal land restoration efforts.

There are certain other provisions which tribes recognized after 1934 could use to satisfy the federal requirements, but those provisions are often more subjective, as the Mashpee Wampanoag tribe in Massachusetts has learned.

The new assistant secretary for Indian affairs at the Interior Department, Tara Sweeney, issued a ruling pulling the Mashpee lands out of trust after she determined that the tribe didn’t have enough interaction with the federal government prior to when it was officially recognized in 2007.

It was a shocking decision, particularly since the former assistant secretary had stated publicly that there was virtually no chance of the trust status being revoked. Not to mention, the Mashpee met several other criteria that have historically been enough for the Interior Department to uphold sovereignty.

That leaves all tribes that weren’t federally recognized in 1934 — such as the Poarch Creeks, which were recognized in 1983 — in a precarious position. They now have no idea what to expect from the Interior Department and Trump administration.

And for PCI, that is a potentially big problem. Because it also lacks the protection of a compact with the state of Alabama.

As Alabama’s gambling fight has unfolded, PCI has offered numerous times to enter into talks with the state to draw out the terms of a compact. But those talks have never materialized — mostly because state leaders have feared the state’s conservative voters would punish any lawmakers who pushed for a deal.

The up side to that is that PCI has been able to rake in untaxed cash hand over fist. The down side is the current national climate. A climate so hostile that even if the tribe seeks to sit down and negotiate in good faith, there’s no certainty that the Interior Department, led by Ryan Zinke, would work in the same good faith.

In fact, there is evidence that it would do the exact opposite, as the Mashantucket Pequot tribe in Connecticut is learning. Even after striking a deal with the state, Zinke’s office refused to sign off on a new casino for the Mashantucket tribe. A subsequent lawsuit claims Zinke’s motivation to kill the deal — which had been approved by Interior Department advisors — was a lobbying campaign by MGM casinos, which is building a new casino near where the Mashantucket casino was planned.

That, too, is a fairly unprecedented move — the Interior Department altogether killing a proposed deal between a state and a recognized tribe. Usually, the department would force amendments to any deal it felt didn’t benefit the tribe enough. But it wouldn’t kill a deal outright.

If you’re in PCI’s shoes, none of this is good. It needs protection moving forward from an administration that doesn’t follow any rules or established protocols. And it will have to get any deal with the state past that same Interior Department.

To make sure it happens, PCI will need friends. Lots and lots of friends.

Which likely explains why they made so few enemies in the last election cycle.