If the findings of a special grand jury empaneled to hear allegations of wrongdoings against former Gov. Robert Bentley and his cronies sound familiar, it should.

In 2012, after an eight-month investigation, a Montgomery grand jury found that the state’s ethics and campaign finance laws were not specific enough to indict former Gov. Bob Riley and then-Speaker of the House Mike Hubbard.

Alabama campaign finance laws remain full of loopholes, Senator seeks reform

So also were the findings in the Bentley investigation, according to its report, the laws were insufficient to prosecute.

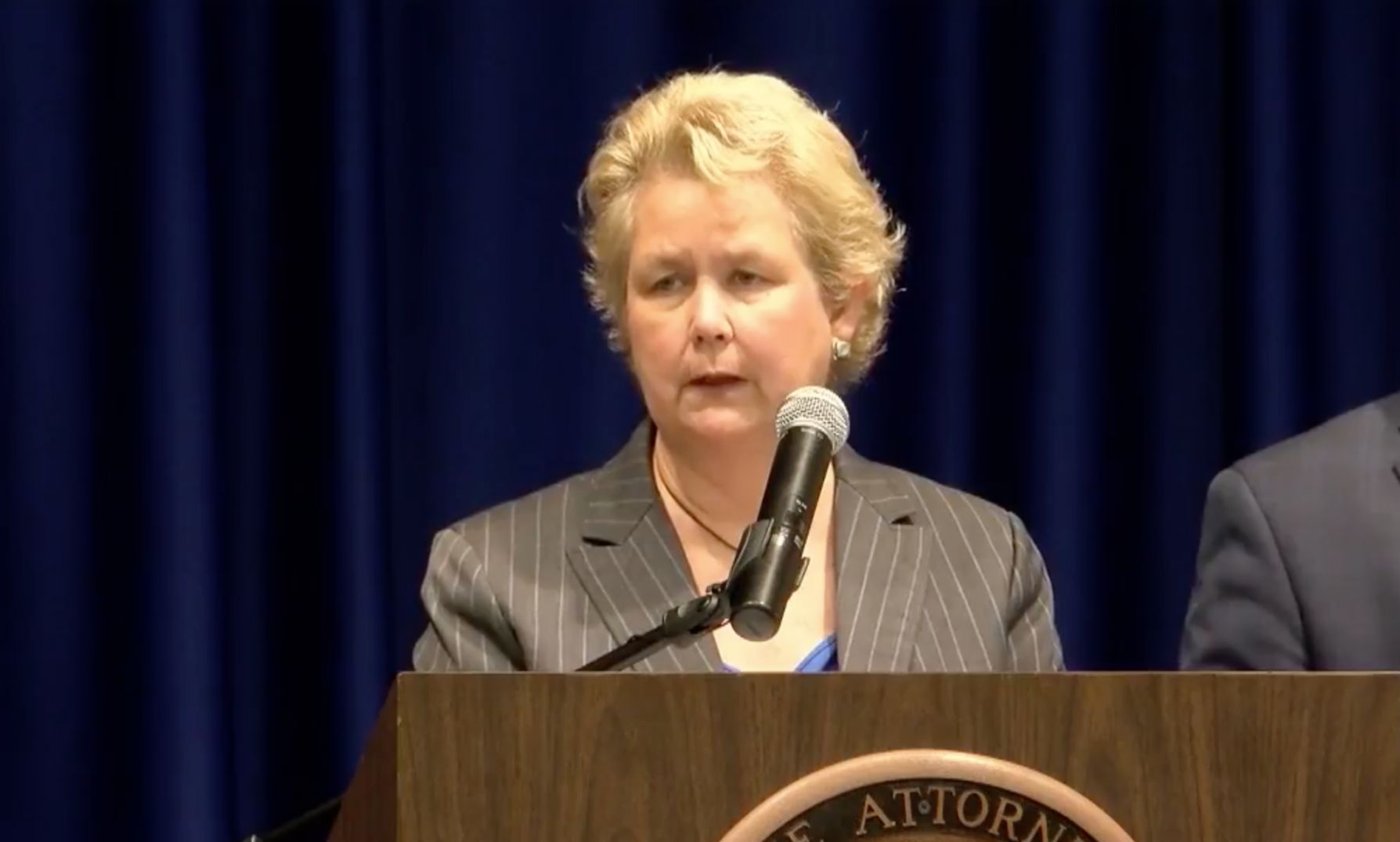

There is at least one distinct tie between these two grand juries – both were led by Ellen Brooks, the former Montgomery County District Attorney.

In both cases, Brooks found that state laws were inadequate to prosecute, thus letting Bentley walk free in 2018, and Riley and Hubbard in 2012.

In 2018, as in 2012, Brooks provided a list of problems with the laws that needed to be strengthened or clarified by the Legislature in case someone else dares commit the same acts.

However, in the Riley-Hubbard investigation, Brooks listed the alleged violations committed by the pair. In Bentley’s case, she allowed no such revelation of facts, leaving the public clueless about the details while calling on lawmakers to fix the loophole.

Brooks enumerated 12 different times Riley and Hubbard made PAC-to-PAC transfers that seemingly violated the very laws they had just enacted but failed to do the same with Bentley’s alleged wrongdoings.

In both cases, Brooks found that state laws were inadequate to prosecute, thus letting Bentley walk free in 2018, and Riley and Hubbard in 2012.

In the Riley-Hubbard probe, Brooks concluded that under the 2012 laws, “No individual is identified to be held responsible and prosecutable for any criminal violation pertaining to a political action committee (PAC) under the act.” She further wrote, “It is not a crime for a PAC to solicit or receive an illegal contribution, such as from another PAC.”

As for Bentley, she states, “Bentley could not be prosecuted for personal gain in office due to the current status of the state’s ethics laws.” Brooks listed three areas of concern:

The Ethics Act does not cover non-spousal, intimate or romantic relationships.

The law authorizes the Governor to appoint the Secretary of Law Enforcement and does not prohibit the Governor from initiating, directing or receiving reports on criminal investigations for illegitimate political purposes.

State law does not prohibit non-government personnel from performing the functions of a public employee while receiving payment from a private entity for that work (so-called loaned executives), and there is a question whether the Ethics Act clearly covers such individuals.

Investigation into the Bentley concludes with no charges, report calls for stronger ethics laws

The public was made aware of what Riley and Hubbard did – why not Bentley and his pals?

Perhaps it shouldn’t be surprising that, once again, a Brooks led grand jury was unable to find lawbreaking because there were no laws to break.

In the Riley-Hubbard affair, the investigation fell to Brooks because the complaints were made in her jurisdiction. But in the Bentley situation, Brooks was appointed by Attorney General Steve Marshall, who, in turn, was selected by the man she was prosecuting.

As APR reported last week, Bentley tapped Marshall as AG after he agreed to investigate Special Prosecutions Divison Chief Matt Hart and Acting Attorney General Van Davis.

Sources: Marshall appointed AG after agreeing to investigate “rogue” prosecutors

In an interview conducted by U.S. News, Republican State Rep. Ed Henry from Decatur may have revealed the plot that led to Bentley’s exoneration. Henry met with Bentley the same day he held a private meeting with Marshall. Henry says he warned Bentley against naming then-Attorney General Luther Strange U.S. Senator to fill the seat vacated by Jeff Sessions.

‘I’m not going to be indicted, I get to appoint his successor.’

“Henry says he cautioned Bentley against appointing Strange, only to hear a jaw-dropping explanation from the governor,” according to the U.S. News. “I met with Gov. Bentley the day he appointed Strange and told him, ‘If you do this, you will be impeached,’” Henry recalls. “Gov. Bentley’s reply to me was, ‘Ed, we have to get rid of him. He’s corrupt.’ And I said, ‘You’re going to appoint someone who you believe to be corrupt to the U.S. Senate?’ He said, ‘We have to.’ I said, ‘Even if that means you most likely will be indicted or impeached?’ He said, ‘I’m not going to be indicted, I get to appoint his successor.’”

Bentley’s official calendar shows he met with Marshall at 8:00 a.m. on February 8, he met with Henry an hour later at 9 a.m. which confirms Henry’s timeline..

By the time Bentley had his meeting with Henry, he had already received Marshall’s assurance concerning Hart and Davis according to individuals with knowledge of the meeting. Perhaps Bentley had also gotten other concessions from the soon to be announced attorney general.

How oddly ironic that the same prosecutor would find such similar conclusions in two separate high-profile cases involving public corruption at the highest levels of state government. But perhaps it is neither ironic or coincidental because is was Bentley appointee Marshall who personally selected Brooks who had a history of not finding wrongdoing because of state law inadequacies.

Special Grand Jury Report by Chip Brownlee on Scribd