By Chip Brownlee

Alabama Political Reporter

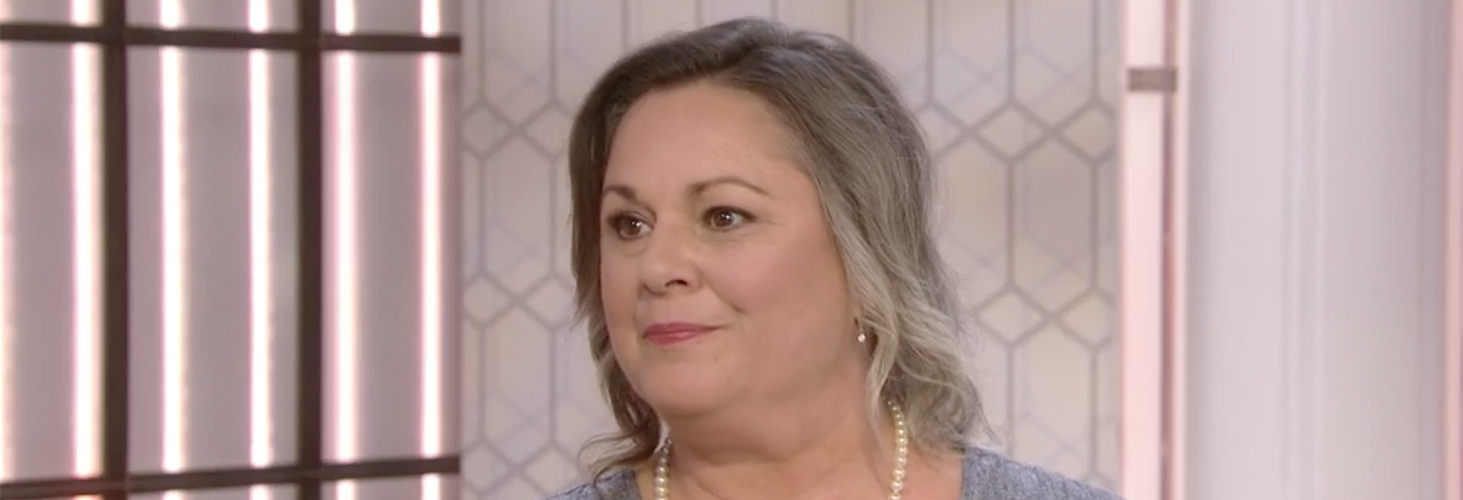

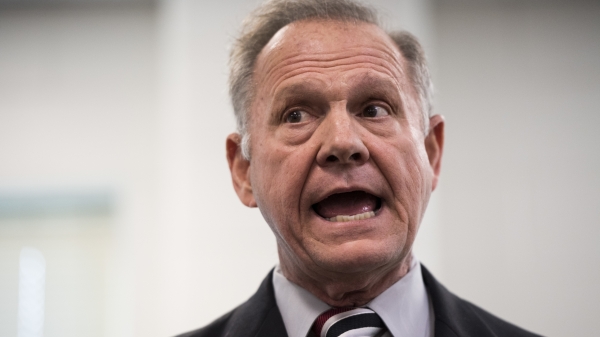

The first of the now nine women to have made accusations against U.S. Senate candidate Roy Moore — faced with questions from some over her decision to come forward decades later — made her first appearance in front of television cameras Monday in an interview on NBC’s Today.

Leigh Corfman, who accused Moore of initiating sexual contact with her when she was 14 and he was 32, said she waited to come forward for a variety of reasons, one of them being her young children.

“I did tell people, my family knew, family friends knew, my friends knew. I spent a lot of time every time he came up railing against him and what he had done to me when I was 14 years old. My children were small. I was a single parent, and when you’re in that situation you do everything you can to protect your own,” Corfman said, directly addressing those who have been critical of her timing.

The Moore campaign called the accusations from the women a political hit job. Moore’s wife, Kayla, has posted on her Facebook page claims that the women have been paid to come forward. There hasn’t been any proof or reliable reports of any payments.

Corfman said Monday that she had not been paid or compensated.

Moore has been a high-profile figure in Alabama politics for decades, going back to his time as an Etowah County Circuit Judge when he first developed his nickname “The Ten Commandments judge.” Through two controversial runs for the Alabama Supreme Court and his two subsequent removals, no allegations surfaced. Corfman remained quiet.

Corfman said she went to the courthouse once to confront Moore but decided against it because she was worried about the backlash — and her kids.

“I sat in the courthouse parking lot and thought, ‘I’m going in, I’m going to confront him,'” Corfman said, recalling a time when she almost confronted Moore in 2000 or 2001. “I wanted to walk into his office and say, ‘Hey, do you remember me? You need to knock this stuff off. I need to go public.’ My children were small, so I didn’t do it.”

Moore is not the only public figure to face accusations of sexual assault in recent weeks — from Democratic U.S. Sen. Al Franken of Minnesota and comedian Louis C.K. to broadcaster Charlie Rose and actor Kevin Spacey — in what has been marked as a shift in the landscape for both accusers and the accused.

Corfman first went public with her accusations against Moore in an article in the Washington Post nearly two weeks ago. Corfman says Moore approached her and her mother outside of the Etowah County courthouse in 1979 when they were attending a custody hearing. He offered to watch her outside while her mother went in for the hearing. He then asked for her number and if he could call her sometime, she said.

He later picked her up twice, a few blocks over from her house, without her mother’s knowledge. The second trip to his rural Etowah County home ended with Moore taking off both their clothes and touching her over her underwear, she said. When he tried to get her to touch him over his underwear, she pulled away and asked to go home, she said, and he took her.

“I was a 14-year-old child trying to play in an adults’ world, and he was 32 years old,” she said.

Moore, at the time, was an upstart assistant district attorney and she was younger than the age of consent.

Corfman, in her interview on Today, said she considered confronting Moore a second time when her kids were a bit older than they were in 2001. But she again decided against it when her kids asked her not to because they were afraid of being outcast at school.

“They were afraid that with all of their social connections that they would be castigated in their groups,” she said. “We decided together that we wouldn’t do it at that time. When the Washington Post saught me out … I had to make a decision.”

Two other women, Beverly Young Nelson and Tina Johnson, told the Post and AL.com that Moore assaulted them, too. Nelson said last week that Moore tried to force her into a sexual encounter outside of the restaurant she was working at as a waitress in 1977 when she was 16, and Johnson said Moore groped her buttocks after a meeting in his Gadsden law office in 1991. She was 28.

The other six women have accused Moore of a range of actions, from dating them when they were teenagers and he was in his 30s to persistently pursuing them when they were between the ages of 16-18. Some said Moore repeatedly asked them out on dates at their high school, and another said Moore forcibly kissed her after a date.

Moore has denied all of the allegations but specifically denied the allegations put forward by Nelson — with his campaign actively working to discredit her in particular in a release Monday that picked apart her account, citing two women the campaign says are former employees of the restaurant where Nelson worked. The two women, Renee Kiser Schivera and Rhonda Kiser Ledbetter, who, according to public records, are sisters, said in statements that Nelson would have had to be 16 to work at the restaurant, Olde Hickory House.

Nelson said she was 16 when the assault happened but was 15 when she started working there and Moore began approaching her. The sisters say they worked there between 1977-1979 but don’t remember Nelson working there or Moore ever being a frequent customer. Nelson said the assault occurred in December 1977, and she quit the next day.

“I never went back there again,” Nelson said.

Rhonda Ledbetter also attempted to poke holes in the details of Nelson’s account, including the time when the restaurant closed, where the dumpsters she was allegedly assaulted near would have been, and if there would have been space behind the restaurant for Moore to park in.

Nelson, in her account, said Moore offered her a ride home but instead pulled around to the back of the restaurant and assaulted her.

“We were always told to park on the side of the building because there just wasn’t much room behind it,” Rhonda Ledbetter said in the campaign’s “debunk.” “I don’t remember there being an exit from the back of the parking lot, there would barely have been enough room to turn a car around.”

Aside from two sisters, the campaign also cites a man they say is a former Gadsden police officer who frequented Olde Hickory and said he never saw Moore there, never met Nelson and “couldn’t say that she even worked there.”

The campaign has also attempted to cast doubt on her only piece of hard evidence, a yearbook she said he signed in 1977 days before he assaulted her. They have requested the yearbook be turned over to an analyst because they believe the inscription was forged.

“The days of unbiased reporting are over,” said Brett Doster, a Moore campaign strategist. “The liberal media will dodge any source and refuse to air any interview that doesn’t square with their effort to land a liberal Democrat in the Senate seat.”

The embattled candidate has also denied Corfman’s allegations, saying he doesn’t know her or remember her, but his campaign hasn’t launched an extensive attack against her allegations as they have with Nelson’s.

“I wonder how many ‘me’s’ he doesn’t know,” Corfman said.

Despite calls for Moore to withdraw from national Republican leaders from Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell to Sen. John McCain, Moore has said he is staying in the race. The Republican National Committee, the Senate Leadership Fund and the National Republican Senatorial Committee have severed fundraising and financial support from his campaign.

State leaders, on the other hand, from Gov. Kay Ivey to the Alabama GOP Steering Committee, are standing by Moore. The GOP has said they will not disqualify him as a candidate.

You can watch the full interview here: