By Josh Moon

Alabama Political Reporter

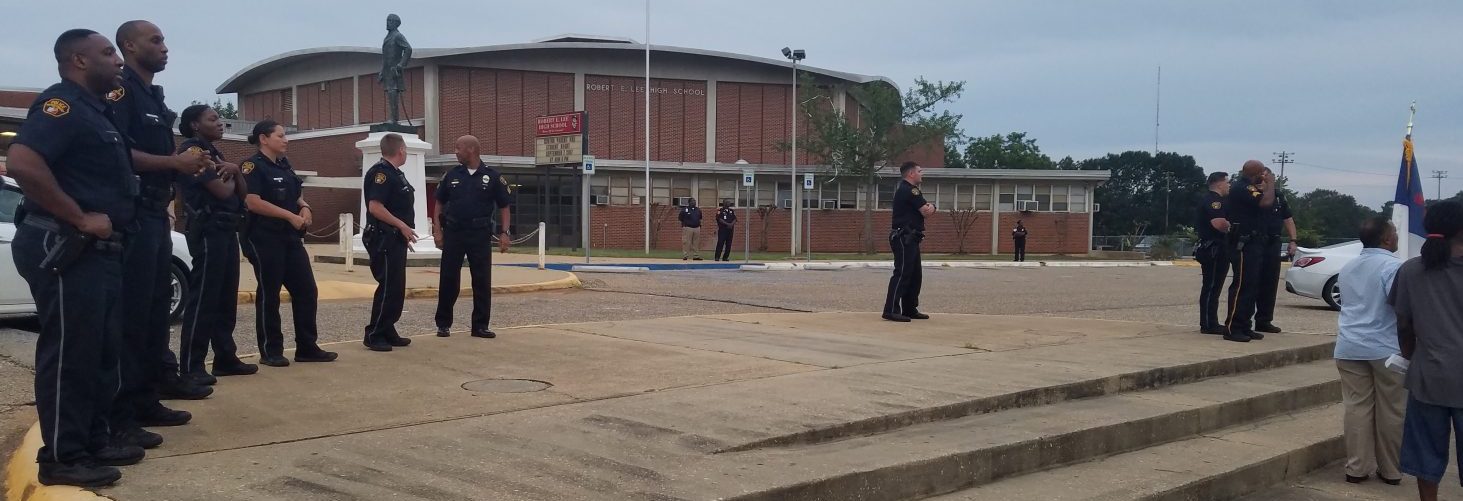

Police departments aren’t messing around with protests of Confederate monuments.

At a sparsely-attended protest in Montgomery on Monday evening against a Robert E. Lee statue that stands in front of a high school bearing Lee’s name, police officers outnumbered protestors by at least 6-to-1. In addition, Montgomery Public Schools officials, searching for any rule that would mitigate the potential for violence or vandalism, refused to allow the public on the campus, because, MPS spokesman Tom Salter said, the school’s band was still practicing.

It was a comically large reaction to a comically small protest, but it underscores a heightened sense of caution around the country, as cities, particularly in the South, deal with growing discomfort over the honoring of Confederate figures or the South’s role in general.

Monday’s protest, such that it was, was organized by a local activist named Ja’Mel Brown – a quirky, outspoken, sometimes pastor who once had a semi-serious run for mayor. For much of the protest, Brown stood, holding a Christian flag, and talking to another man who was holding a phone and broadcasting Brown on Facebook Live.

The only bit of a excitement for the horde of cops was when two other men – one wearing a t-shirt proclaiming him to be an “Infidel … and proud of it,” and the other who claimed to be a former coach and history teacher – approached Brown and began shouting arguments at anything he said.

As Brown spoke about Lee being a traitor and owning slaves, the former history teacher shouted, “Slavery’s been over thousands of years!”

Brown ignored the shouts. The men kept shouting.

Finally, and mostly out of boredom it seemed, an MPD officer sighed deeply, walked over and made the two sides separate.

The large police presence didn’t come about out of the blue.

At an MPS school board meeting last week, activists requested that the board explore removing the statue from in front of the predominately-African American high school. Board members promised to form a committee to explore the idea and get community input.

The response on social media was hostile and embarrassingly racist. And when online fliers promoting Monday’s protest began to circulate, they quickly found their way to Facebook groups dedicated to supporters of Confederate monuments. Over the last two days, posts on Brown’s Facebook page received a number of comments from people with Confederate flag avatars advising him against holding the protest.

Brown also claimed a city official contacted him and told him that his protest had been reported to MPD and the FBI for potential “terrorist threats.” Apparently, Brown’s use of the hashtag “usorelse” led people to believe he was threatening violence. Brown posted screenshots of messages from people who were as far away from Kentucky complaining about his protest.

But for all of its online hype, there was little physical response.