By Brandon Moseley

Alabama Political Reporter

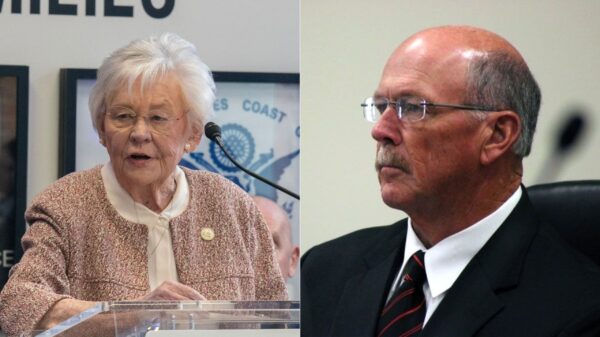

Tuesday, July 18, 2017, the Commissioner of Alabama Department of Agriculture and Industries, John McMillan (R) confirmed that the department is working with USDA officials to address a positive test for atypical bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), known in the popular press as “Mad Cow Disease” in an eleven-year old Alabama beef cow.

On Wednesday, The Alabama Political Reporter (APR) spoke with the Alabama Cattlemen’s Association Executive Vice-President Erin Beasley about the developing situation. Beasley told APR that this is an isolated case and that it proves that the protocols that were in place to safeguard the public and the food supply are working.

APR also reached out to the Alabama Department of Agriculture and Industries. Department of Agriculture Federal Affairs Director Hassey Brookes answered several questions that APR had.

APR: Alabama is a big place. Can you release which stockyard?

Brookes: No.

APR: Which county is the cow from?

Brookes: Will not release.

APR: What breed of cattle?

Brookes: Black Angus type.

APR: Does she have retained heifer calves that are still on the farm?

Brookes: Under investigation.

APR: If so are they being tested?

Brookes: We are partnering with the USDA on the monitoring & observation.

APR: Since there have been only a half dozen of these in all of the United States and two were in Alabama (a Santa Gertrudis cow in 2006 was the other), is there some sort of an environmental factor involved that would cause this to spontaneously appear more frequently than in the rest of the nation’s cow population?

Brookes: No.

APR: Was this cow fed or exposed to chicken litter (a controversial practice temporarily banned at the height of the Mad Cow crisis 15 years ago)?

Brookes; This question will be investigated.

The Angus cow was showing clinical signs of the disease. The veterinarian at the livestock market identified the cow as being of interest, correctly identified the cow as being BSE positive, and ordered the cow isolated, it later died at the livestock market and samples were taken and sent to the USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) National Veterinary Services Laboratories (NVSL) which confirmed the diagnosis on Tuesday.

According to Commissioner McMillan, this was an atypical BSE case, meaning it is a rare and spontaneous incident. Unlike previous cases of classical BSE, this case is not the result of ruminant by-products being fed to ruminants. The United States banned the use of such protein supplements in cattle in 1997.

In 2009, the USDA implemented the enhanced surveillance testing programs to protect animal and human health. Included in the regulation was the removal of specified risk materials – or the parts of an animal that would contain BSE – from all animals presented for slaughter. Another important component of the system – which led to this detection – is the ongoing BSE surveillance program that allows USDA to detect the disease in the US cattle population.

Agriculture is Alabama’s largest industry.

Commissioner McMillan said, “The Alabama beef industry is vital to our state’s agriculture economy. The response to this case by USDA officials and our department’s professionals led by State Veterinarian Dr. Tony Frazier has been exemplary. This instance proves to us that our on-going surveillance program is working effectively.”

State Veterinarian Dr. Tony Frazier added, “The ADAI conducts routine surveillance that includes collecting samples by trained field staff and veterinarians and has a response plan in place.”

BSE is not contagious and exists in two types: classical and atypical. Classical BSE is the form that occurred primarily in the United Kingdom, beginning in the late 1980s and it has been linked to variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (vCJD) in people.

For more information and questions about BSE click here.