By Josh Moon

Alabama Political Reporter

If Alabama’s ethics laws weren’t designed to prevent the actions of former House Speaker Mike Hubbard, then they’re essentially useless.

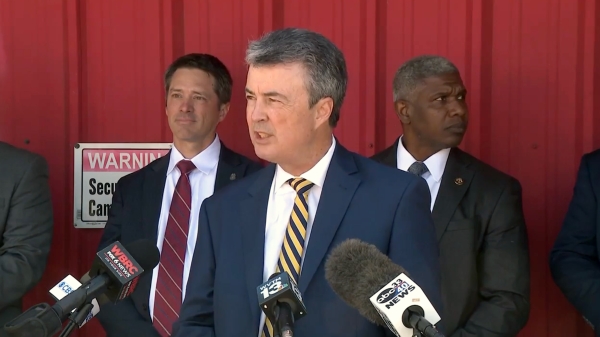

That was the opening of the State of Alabama’s response to Hubbard’s filing last month in his appeal of 12 felony counts. The 138-page response from Attorney General Steve Marshall picked apart the arguments in Hubbard’s appeal, focusing on the basics of the law and grinding the allegedly complicated laws down to common sense right and wrong.

“Hubbard’s conduct goes to the very heart of what the ethics laws prohibit,” the State’s filing reads. “At every turn, he sought to use his position to benefit himself and his businesses, while hiding the true nature of his interests from his colleagues, the public and his staff.”

It is, essentially, what I’ve written about Hubbard and this case from the beginning: Whatever technical, nitpicking arguments Hubbard and his team of attorneys might make in order to manufacture a gray area in which his actions might seem more legal, there is no doubt that those laws were created in order to prevent the actions that Hubbard took.

Take the count in which Hubbard was found guilty of a soliciting a thing of value from Edgenuity, an education company. Even if you believe that poor ol’ Hubbard was barely scrapping by on a couple-hundred grand per year and that he was just trying to feed his family and do so on the up-and-up when he signed a $7,500-per-month contract with Edgenuity to “consult,” you still have to explain one thing.

Why did Hubbard tell the folks at Edgenuity not to put his name on the contract, to instead put down his company, the Auburn Network?

I’ll tell you why: Because a House member, much less the Speaker, shouldn’t sign a consulting contract in which that member uses his or her legislative influence to benefit his employer.

Hubbard knew it. That’s why he hid it.

And if you doubt Edgenuity was buying Hubbard’s influence as a lawmaker, explain this second thing: Why would that company pay out $7,500 per month to a guy who admits to having no clue what Edgenuity actually does?

Because that’s what Hubbard admitted in an email shortly after signing up with Edgenuity. He literally asks where he can find information about the company.

Common sense tells you that ain’t right.

And that’s basically what the State’s filing on Wednesday does – it lays out the common sense, “oh come on” retorts to Hubbard’s appeal filing, going count by count.

Most of it we’ve all heard before.

However, there is some new stuff mixed in.

In his appeal, Hubbard alleged – and this isn’t exactly new – that there was prosecutorial misconduct and that former Alabama Ethics Commission executive director Jim Sumner’s testimony was improper. He also claimed after the trial that there had juror misconduct, because, why not.

The State’s response goes about breaking those things down in detail for the first time and pointing out the flaws in Hubbard’s logic.

First and foremost, on the issue of prosecutorial misconduct, the guilty verdicts all but killed that argument.

Prevailing case law basically says that in most cases any alleged grand jury misconduct is negated by the fact that a jury found the accused guilty beyond a reasonable doubt.

After all, it’s hard to claim there wasn’t probable cause to support the charges when a jury finds you guilty of those charges.

It’s also hard to claim that the guy who served as the executive director of the Ethics Commission, the guy who literally conducted classes on the ethics laws, the guy who lawmakers – even a guy named Mike Hubbard – turned to for interpretations of complicated ethical situations was somehow not an expert on ethics laws.

But that’s also what Hubbard’s team tried – claiming that the court erred in considering Sumner an expert.

Good luck with that.

And finally, there was the jury misconduct that Hubbard’s team managed to turn into news for several days. For all of the hoopla, you would have thought they had evidence of Matt Hart going full-on Oprah and handing out new cars to jurors in exchange for guilty verdicts.

Except, it wasn’t that. Not even close.

One lady was allegedly whispering to herself after some testimony, another allegedly said, “yeah, right,” during jury questioning, some allegedly talked about upcoming witnesses and wondered why Hubbard needed so much money and some allegedly thought Hubbard should plead guilty.

That’s it.

And even if any of these things had been semi-serious, Hubbard’s legal team forfeited any chance to appeal his convictions because of them when they failed to subpoena the jurors for questioning – even after the court notified them of their responsibility. Instead, they wanted the Lee County Sheriff’s Office to investigate.

I suspect Hubbard’s attorneys knew the futility of questioning those jurors. And in reality, the allegations were simply one more attempt at creating a loophole through which Hubbard might wiggle out.

By now, I think everyone is on the same page when it comes to Mike Hubbard and the ethics laws he broke. If not, the state’s filing does a nice job of summarizing it.

“If Hubbard’s conduct is not prohibited by the ethics laws, then the laws are a sham designed to let lawmakers disguise unethical conduct with a veneer of legality.”