By Chip Brownlee

Alabama Political Reporter

MONTGOMERY — Gov. Robert Bentley’s priority legislation for the 2017 legislative session has made it through the Alabama Senate, but only an outline of the original plan remains in place.

The Senate on Thursday passed a toned-down version of Bentley’s Prison Transformation Initiative — an ambitious, albeit controversial plan to reform the landscape of Alabama correctional facilities by consolidating almost all of the men’s prisons into three “mega-prisons.”

The original plan, sponsored by Sen. Cam Ward in the Senate, called for building four new prisons at a cost of $800 million. Three of the prisons would have held 4,000 male offenders a piece, and one would have held 1,200 women. Their location had not been decided.

A bond would have been issued to cover the costs.

The first iteration of the Alabama Prison Transformation Initiative had strong support among the upper echelons of the Alabama Legislature. But the plan faced fierce opposition from rank-and-file members of the Legislature, who raised concerns over bidding, transparency, cost and the location of the new prisons.

The final version of the bill authorizing Bentley’s plan passed by the Senate Thursday looks little like the original plan but keeps the basic outline of three new mega-prisons for men. It scraps the new female facility. Bentley seemed at ease with the changes in a statement released Thursday afternoon from his office.

“I understand this bill is a work in progress and my ultimate goal remains the same, and that is to have safe and modern facilities that solve the persistent overcrowding of our prisons that will protect our law enforcement officers and inmates, as well prepare the inmates to successfully transition back into our communities,” Bentley said. “If we are to truly transform the person, we must first transform the system.”

Instead of four new prisons, the legislation passed will only authorize three new men’s prisons.

And instead of an $800 million bond issued by the State, the new legislation only authorizes the Department of Corrections through a bond authority to take $325 million in bonds for one new prison and renovations of existing facilities.

But ADOC can only take out the bond if they find two localities go first.

Under the legislation passed Thursday, the first two prisons will have to be financed by county or local authorities. The localities must establish their own bonding authorities and borrow up to $225 million to build the prisons, which would then be leased back to the State.

The Department of Corrections would first have the authorize the bonds and the plans before any construction began. The localities would have to meet State standards to be considered.

The local requirement first began as a local option.

In a compromise plan crafted last week, localities were allowed to build their own prisons, but they weren’t required to go first. Several legislators, including Sen. Greg Albritton, R-Bay Minette, and Sen. Clyde Chambliss, R-Prattville, asked for the local option to assuage concerns in their districts over the possible loss of jobs from prison consolidation.

The senators wanted to guarantee that Escambia and Elmore Counties would be able to compete for the new mega-prisons to replace any lost jobs. Escambia and Elmore Counties alone are home to seven of Alabama’s 16 major correctional facilities — not counting work-release and community work centers in the counties.

Officials from both counties have said they would be interested in supporting the new correctional facilities, but many other counties may not have the resources to compete for the new prisons.

A local official from Barbour County, Alabama, home to two major correctional facilities, who spoke with APR on background, said their county wouldn’t be able to compete because it couldn’t support such a large bond issue.

ADOC’s initial proposal for the APTI would have consolidated 14 of Alabama’s 16 major correctional facilities into the four new prisons. With the new plan, it is unclear how many facilities will be closed.

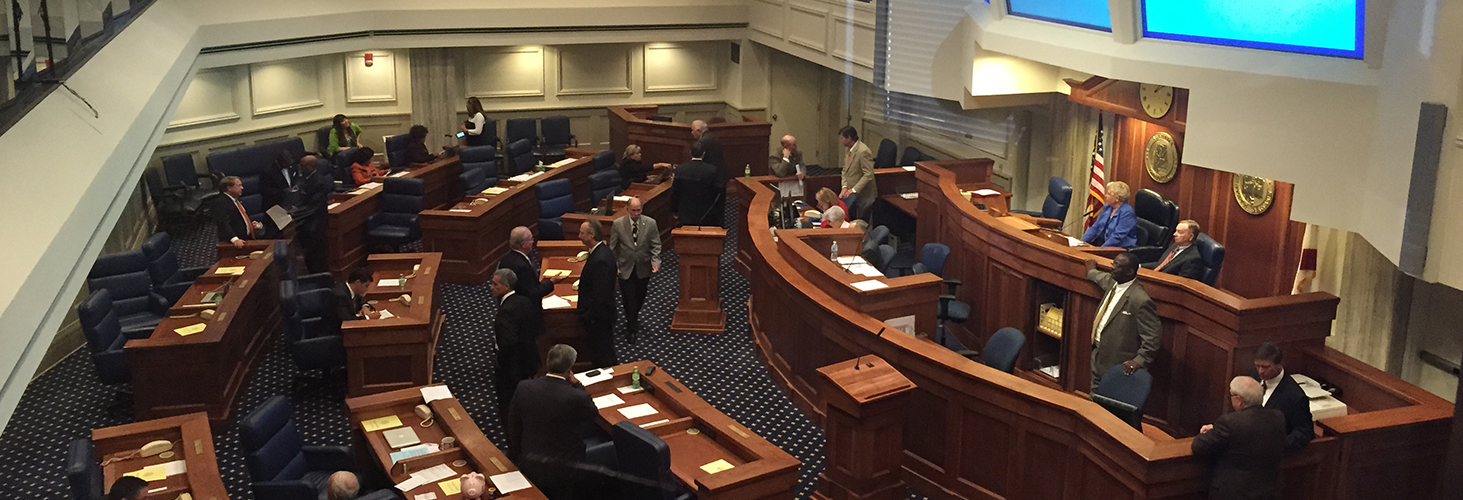

The plan got several hours of heavy debate on the Senate floor Thursday afternoon, but 23 senators eventually voted yes on the measure. Now it will head to the House of Representatives for consideration.

The legislation split the parties with 19 Republicans and four Democrats voting in favor, while seven Republicans, three Democrats and an independent voted against it, citing concerns over the still-looming costs.

The Alabama Prison Transformation Initiative was conceived by ADOC Commissioner Jeff Dunn and was intended to alleviate several major problems in Alabama’s prisons: increasing costs, dangerous overcrowding and understaffing.

By consolidating the prisons into three mega-facilities, the State could save $50 million a year — enough to finance the bond payments — and wouldn’t need as many guards, ADOC officials have said.

“The State prison system is close to exploding the state budget,” Ward said. “We have numerous prisons that were built before the Vietnam War and some pre-date World War Two. The upkeep alone for these facilities is a bleeding hole in our budgets.”

Though the plan is an attempt to address overcrowding and systemic understaffing problems, it doesn’t completely alleviate them. The plan would only reduce overcrowding from about 175 percent capacity to a little more than 125 percent capacity over the next five years —and only if all three prisons are built.

Alabama’s prisons currently house about 23,000 inmates in a system built mostly in the 1970s for a max of 13,000 inmates, according to the most recent ADOC statistical reports. Bentley’s plan would have only increased capacity to 16,000 inmates if the planned number of existing prisons were closed.

The final version passed Thursday would only bump capacity by about 2,000. Depending on the size of the new prisons and how many are built, capacity could be increased by an even smaller percentage.

The State prison population has decreased from about 27,000 after the Legislature passed sentencing reform measures in 2013. The new prisons, combined with sentencing reform, could solve the overcrowding problem over time, proponents have said.

The Montgomery-based Southern Poverty Law Center, a legal organization currently carrying several lawsuits against Alabama over health care access in its prisons, said the plan would not solve problems of violence, understaffing and lack of adequate health care.

“We all agree that many facilities need renovating, and in some cases replacing, but we shouldn’t move forward with an expensive construction project without a comprehensive strategy to overhaul the prison system and the criminal justice policies that helped create this crisis,” said Ebony Howard, an SPLC associate legal director.

Ward has said he favors an “all of the above” approach, which could include more sentencing reform.

“You’ll never be able to build your way out,” Ward said. “What this does do, combined with sentencing reform, is it gets you to the 137 percent capacity. That would be the steepest decline without endangering public safety of anybody in the country.”

The Federal Judiciary has shown increasing impatience with Alabama’s prison system. In recent years, conditions at Tutwiler Prison were so bad that a Federal court ruled them unconstitutional and ordered improvements.

But the plan passed Thursday cut out a new Tutwiler. Instead, it allows for some of the bond capital to be used for renovations at the existing Tutwiler. Tutwiler was originally Bentley’s first priority, citing the court cases against it, but Ward said it was the first to go because the State wouldn’t save any money from building a new one.

In 2015, the State settled a lawsuit by the US Department of Justice against conditions at Tutwiler. As part of the agreement, ADOC put millions into renovations at Tutwiler, which could continue under this new plan.

“There was really no savings with doing a new women’s prison,” Ward said last week. “What we were closing down would not generate enough in savings to do another.”

ADOC has said the consolidation using the “mega prisons” would reduce staffing costs by about $17 million a year, overtime payments by $21 million a year and healthcare delivery by $10 million, according to the two independent studies the department commissioned.

The exact savings all depend on the size of the new prisons built by the localities — if they’re built at all.

Email Chip Brownlee at cbrownlee@alreporter.com or follow him on Twitter.