By Chip Brownlee

The Alabama Political Reporter

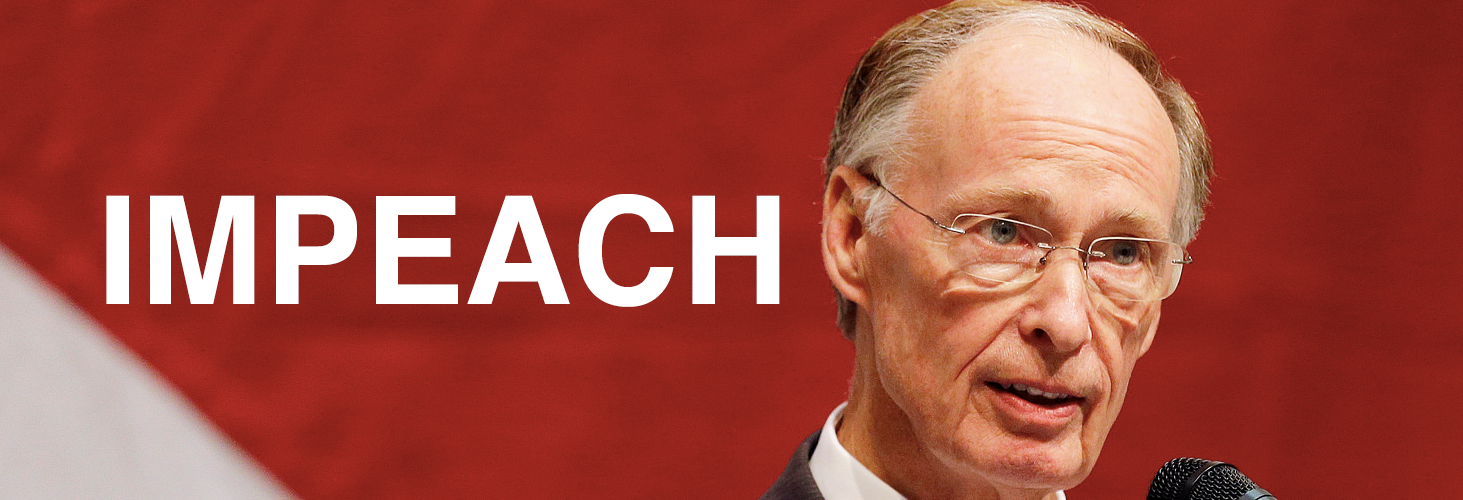

MONTGOMERY— The committee charged with investigating Gov. Robert Bentley’s “impeachable” acts began flexing its muscles Tuesday afternoon, but with their new show of force, questions about the reality and authority of those muscles persist.

At a House Judiciary Committee Tuesday, members of the committee passed a set of ground rules intended to lay the tracks for the committee hearing. In those ground rules: an assumed authority to issue subpoenas, and an even-more-assumed ability to enforce them.

“We’re about to send subpoenas out, and we don’t know if we can enforce them,” said Rep. Chris England, a Democrat from Tuscaloosa.

But Jackson Sharman, a high-profile attorney with experience investigating high-profile politicians, said the committee has the authority to both issue and enforce subpoenas.

“I’m convinced you do, and I’m convinced the House does,” Sharman said.

There are two avenues, Sharman said, that the committee could go about enforcing those subpoenas. First, they could send the case to a circuit court and let them find the witness in contempt, or they could simply vote to find the person in contempt themselves.

What would happen then, no one knows, because a court would have to enforce the contempt with an order.

And Sharman wasn’t very clear where his reasoning was coming from, either.

According to him, there was no precedent in state courts that indicate the subpoenas couldn’t be enforced. And even more so, he said the Alabama Constitution implies that the Legislature has the power to issue and enforce them.

Essentially, it doesn’t say they can’t, so they can.

Even though members of the committee couldn’t arrive at a consensus about their own subpoenas, they still passed a set of rules 8–3 Tuesday that will give Sharman and a subcommittee the authority to issue a few, let’s say, important subpoenas.

On that list include the embattled governor himself, his office, his campaign and his alleged mistress, Rebekah Caldwell Mason. Also on the list, Mason’s husband, her public relations and communication firm RCM Communications and a dark-money pact devoted to electing Bentley.

Though a date for the subcommittee to meet about the subpoenas hasn’t been set, Sharman said if they met Tuesday, he could have the subpoenas ready to serve by as soon as Friday. That’s unlikely though. It appeared as if it would be days before the subcommittee could meet.

Even then, that could put Bentley — if he decides to comply with the subpoenas — in a hot seat in front of Committee Chairman Mike Jones and the rest of the committee by their next meeting.

The subpoenas just may be a waste of paper, though, because Bentley’s team doesn’t seem to think they have to cooperate with them even if they’re issued.

“The Judiciary Committee does not have subpoena authority,” said Ross Garber, an attorney representing Bentley’s office. “There’s no statute granting it. There’s not constitutional provision granting it. This committee has no more subpoena authority than you do. … We’ll certainly look at them and evaluate them.”

England and Bentley’s attorneys weren’t the only ones who were confused about the subpoena power. Rep. Juandalynn Givan, D-Birmingham, was also critical of the committee’s decision to give itself and its special counsel subpoena power.

“We’re creating a power that we do not have,” Givan said. “We’re creating a contempt power. We’re creating a subpoena power.”

On the other hand, Sharman said he needs the ability to subpoena Bentley, Mason, her husband and their organization because they all won’t cooperate or even comply with his investigation into Bentley’s affairs. He said he requested documents from them weeks ago, but they didn’t comply.

But Garber and Bentley’s other lawyer, David Byrne, said the governor’s office most definitely did comply — even if it was only hours before Tuesday’s meeting started. They said his office turned over more than 1,500 pages of documents to Sharman’s office Tuesday morning. Included in the documents, travel manifests, payments and other records related to former ALEA Secretary Stephen Collier, Mason and others.

At the meeting, Sharman said he hadn’t had time to review them. And they only decided to turn them over so they could say they did in the meeting, Sharman said.

Subpoenas weren’t the only topic of conversation Tuesday. Sharman’s proposed rules would have made it impossible for Bentley’s legal team to cross examine or interview witnesses for the committee’s record.

After intense debate for hours, an amendment proposed by Givan and passed unanimously by the committee changed the rules to allow for cross examination by Bentley’s team. Had it not passed, Givan said she would have been worried that his due process rights would have been violated.

“To me that appears to be in conflict with his or his counsel’s due process rights,” Givan said.

Sharman said he wanted the committee’s investigation to function like a grand jury, in which all authority and power is given to the prosecutor and little to no right to a vocalized defense are afforded to the defense and his team.

Those rights are reserved for the trial. And in this case, that trial will be in the Senate, if it ever gets there.

Impeachment by the House wouldn’t immediately result in Bentley’s permanent removal from office, the Senate trial would have to do that.

But Garber said Bentley would be temporarily removed from his office if he was impeached by the House, and acquittal in the senate would be the only way he could go back to the governor’s chair.

So everything rests on the committee’s recommendation on whether or not to impeach. So Garber said he wants the committee to hear both sides of the argument.

“This is it, this is the game,” Garber said. “This is the whole thing. If the governor gets impeached, you’re nullifying the votes of the people of Alabama who went out and cast their ballots.”

The impeachment investigation into Bentley — one of several different probes, some even federal — began in April when members of the House filed articles of impeachment against the governor.

Bentley is accused of maintaining an extra-marital affair with one of his top aides, Rebekah Caldwell Mason, and using state funds to do it. He’s also accused of ordering former ALEA Secretary Stephen Collier to subvert a criminal investigation by Attorney General Luther Strange’s office into former House Speaker Mike Hubbard.

The accusations all came to light after Bentley fired Collier, and Collier turned on him and recordings of Bentley’s explicit conversations surfaced the same exact day on the internet. Bentley, despite the recordings, has denied a physical relationship with his aide, but has apologized for “inappropriate comments.”

Only two other governors in the United States have been removed from office in the past 85 years following an impeachment. Fifteen others have been impeached, but weren’t removed from office.

The Legislature tried to impeach a constitutional officer only one other time in Alabama — in 1915 when proceedings were held against then-Secretary of State John Purifoy. Other than that, there is no precedent.

The legislators on Goat Hill today are setting the precedent.