By Bill Britt

Alabama Political Reporter

MONTGOMERY—The future of gaming in Alabama will be a battle between competing businesses, personal and religious interests.

Senate President Pro Tem Del Marsh (R-Anniston) has proposed legislation that would allow competition for gaming revenues between the Birmingham Racecourse, VictoryLand, Greenetrack, and locations owned by the Poarch Creek Indians (PCI). This will also include Mobile Greyhound Park, which is owned by PCI. Marsh’s legislation includes a lottery.

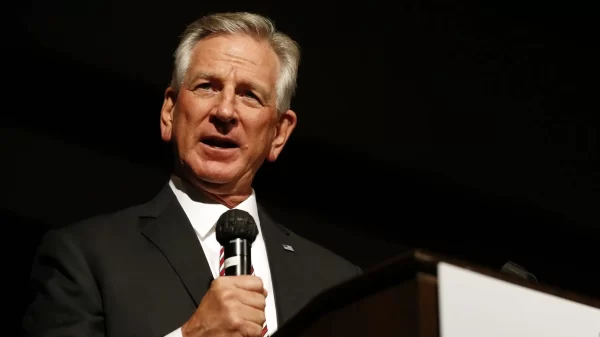

A competing plan reportedly favored by Speaker of the House Mike Hubbard (R-Auburn) would essentially grant PCI a monopoly over all gaming in the State and perhaps a lottery. Hubbard’s reasoning has not been articulated, but much speculation surrounds his motivation.

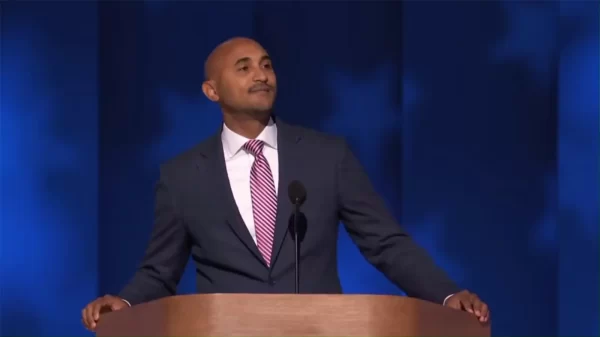

PCI’s Vice Chair Robbie McGhee has stated the tribe would be willing to advance the State as much as $250 million in exchange for an exclusive compact. This would give the tribe sole rights to table games and slots in the State, while giving the State a one-time windfall of needed cash.

The tribe and their lobbyists have conducted extensive meetings with Hubbard, who has, in turn, reached out to Gov. Robert Bentley to press him on supporting the tribe’s position.

Hubbard, who has been charged by the State with 23 felony counts of public corruption which also includes lobbying the Governor on behalf of his clients, is fighting a very expensive legal battle. He has already used hundreds of thousands in campaign contributions to pay for his criminal defense, and some attorneys have suggested that he may need millions to actually see his day in court, with his current level of legal representation.

At odds with both plans are ALCAP, an interdenominational ministry whose mission, according the its website serves as, “Alabama’s moral compass,” and the Alabama Policy Institute (API), a right-wing think thank.

According to Marsh, his plan, which, in part, is based on existing business and free-market competition, would not only generate revenue from taxing gaming, it would also create thousands of jobs.

An exclusive compact with PCI would not result in new, large-scale employment opportunities and would not amount to the reoccurring revenues that would be generated under Marsh’s plan.

Gov. Bentley has said, that gaming is not the answer to the State’s long-term fiscal health. He remains committed to putting the State on a path of stable growth through targeted tax increases.

However, those within the Governor’s inner-circle believe that the Hubbard plan might receive support, if he will deliver on Bentley’s tax plan. it has been said, a number of tax bills will soon be dropped in the House by members with close ties to Hubbard.

In part, the Hubbard/PCI scheme rests on the Governor’s legal authority to unilaterally sign a compact without the approval of the legislature. If the legislature must approve a compact, then Hubbard’s plan could be in jeopardy. It is widely believed that he cannot win over enough Senators to secure passage of a bill that grants a monopoly to the Poarch Creek Indians.

In compact negotiations states are expected to act in “good faith.” The text of Indian Gaming Regulatory Act (IGRA) takes specific notice in not conferring upon a State or any of its political subdivisions the authority to impose any taxes, fee, charge, or other assessment upon an Indian tribe. So, it would be a delicate balance that would have to be reached between the Governor and the tribe.

There are numerous requirements to ensure tribes and states operate in good faith and to negotiate gaming compacts that will harm neither group and benefit, primarily, tribe members. The emphasis, of course, being on no harm to either and on benefitting the tribe not the State.

According to Florida House of Representatives v. Crist, the The Indian Gaming Regulatory Act (IGRA) clearly prohibits the conduct of Class III gaming activities on Indian lands in the absence of a tribal-state compact that is in effect. The only exception to the compact requirement Congress envisioned was the promulgation of a gaming compact through administrative procedures after a bad-faith determination and in concert with a proposal selected by a court-appointed mediator.

In 2008, the Florida House of Representatives and its Speaker, Marco Rubio, filed in petition for a writ of quo warranto in the Florida Supreme Court disputing the Governor’s authority to bind the State to the compact that he had signed with the Seminole Indian Tribe of Florida. The Court held “that the Governor does not have the constitutional authority to bind the State to a gaming compact that clearly departs from the State’s public policy by legalizing types of gaming that are illegal everywhere else in the state.”

The same argument was made in North Carolina, where, in 2012, the North Carolina Institute for Constitutional Law found that Governor Bev Perdue “appear[ed] to have exceeded the scope of her authority when she signed the Gaming Compact that expanded current gaming options for the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians.”

This was because live table games were not permitted by state law at the time the Governor entered into the compact. This issue was later resolved with by the State’s General assembly.

Class III table gaming is currently not legal in Alabama and could take a constitutional amendment to make it so.

Case law undercuts the argument that Bentley or any Alabama Governor can act without consent of the legislature.

On the religious front, the idea of expanding gambling has met with fierce opposition in the past.

When gaming interests tried to pass legislation under the banner of Sweet Home Alabama, Citizens for Better Alabama (CBA) a Birmingham based, tax-exempt group was the public face of the opposition.

Led by Birmingham-based attorney A. Eric Johnston, who also works with ALCAP, hundreds of thousands of dollars were donated to the non-profit to fight gambling.

In a 2013 interview with the Alabama Political Reporter, Johnston explained how, then-Governor Bob Riley and Chairman of the ALGOP Mike Hubbard, routed almost a million dollars in contributions through the non-profit and back to a Hubbard owned company.

The non-profit’s Federal 990 report shows that with the aid of Riley and Hubbard, Citizens for a Better Alabama went from raising only around $40,000 in its best years, to almost a million when it came to fighting efforts to expand gambling.

Hubbard’s alliance with PCI seems to indicate that he will not be on the anti-gambling side on this occasion.

Former API policy wonk turned columnist for al.com has said that the State is not broke, “…just either too stupid or too unwilling to solve the real problems we face.” Smith says that raising tax or legalizing gambling is not the answer.

Smith seems to think that there is enough money in the Education Trust Fund to solve the State’s financial woes, even through the fund has suffered proration five out of the last ten years, and only recently obtaining a sizable surplus.

There is little doubt that organizations like ALCAP and API will press hard to stop in efforts to expand gambling.

Regardless of ideological beliefs or the State’s dire fiscal needs, the expansion of gambling will most than likely come down to political maneuvering and personal financial gain.

If past is prologue, the competing interests could likely destroy each other, before doing what is beneficial for the State. Most people would say it is time for the voters to decide gambling’s fate, but as in most things, the opportunists can’t make money if the voter’s have their say. Many are hoping for a mutually beneficial arrangement settled by the voters and not backroom, deals that line politicos’ pockets.