By Bill Britt

Alabama Political Reporter

MONTGOMERY—The Attorney General’s opinion that has led to public officials using campaign donations to pay criminal defense legal fees, began with the indictment of Jefferson County Sheriff Jimmy Woodward in August of 1999.

According to the Attorney General’s Office, “Often state law can be confusing; therefore, public officials may request that the Attorney General give his legal interpretation of the law in understandable terms.”

While Alabama Code specifically calls upon the Attorney General to issue official opinions about State law, this is an interpretation and not necessarily a binding law, and therefore could be subject to a legal challenge.

The opinion given by Bill Pryor was issued as a result of Jimmy Woodward asking if it was legal for the Jefferson County Commission to pay his legal defense fees and was it legally permissible for him to use campaign donations for his defense?

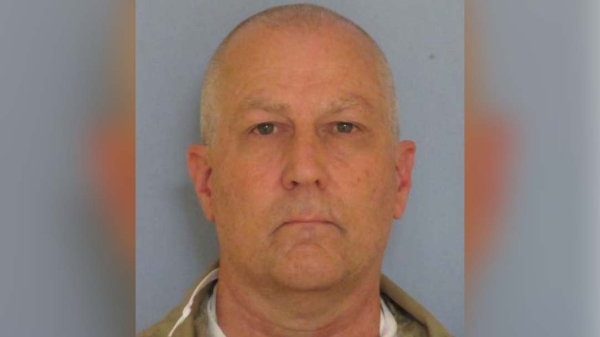

The back story of the opinion starts in August 1999, when Sheriff Woodward was indicted by the Circuit Court of Jefferson County, Alabama, Bessemer Division for the misdemeanor offense of Obtaining Criminal Record Information Under False Pretenses.

The indictment alleged that “while serving as Sheriff of Jefferson County, Woodward improperly, and under false pretenses, accessed the Alabama Criminal Justice Information System in an effort to determine whether those persons who voted in Jefferson County by absentee ballot in the November 3, 1998, general election were all qualified voters.”

In November 1998, incumbent Woodward lost his election for Sheriff to challenger Mike Hale by 37 votes.

According to the Department of Justice records, “Woodward challenged the election and hired [Albert] Jordan to represent him. Jordan filed pleadings which alleged that convicted felons, ineligible to vote, had cast absentee ballots for Hale in the cities of Bessemer and Birmingham.” The records state that, “Jordan and Woodward directed Jefferson County Sheriff’s Department personnel to conduct blanket criminal history searches on the absentee voters in Bessemer and Birmingham,” and that on Nov. 20, 1998, “Woodward initiated a voter fraud task force to further conceal his misuse of public office.”

In his opinion Pryor states, “the county commission of any county of the state of Alabama may, in its discretion, defray the costs of defending any lawsuit brought against any county official when such lawsuit is based upon and grows out of the performance by said official of any duty in connection with his office and does not involve a willful or wanton personal tort or criminal offense committed by the official. The expenses of defending such litigation may include witness fees, transportation, toll and ferry expenses of witnesses, attorney’s fees, court costs and any other cost in connection with the defense of said litigation.”

Here Pryor concludes, “If certain requirements are met, the Jefferson County Commission, in its discretion, may pay out of county funds the legal expenses of the sheriff incurred in connection with a criminal indictment of the sheriff.”

The certain requirements that Pryor states are:

1. The suit must arise from the official of any duty in connection with his office.

2. That they not be relayed to a willful or wanton personal tort or criminal offense committed by the official.

3. That a criminal indictment has occurred.

The payment of legal defense is at the discretion of the commission.

The second question Woodward asked was, “Am I allowed to pay my attorneys fees and other legal expenses from existing campaign funds?”

Pryor writes, “This Office has never addressed the question whether the payment of legal fees incurred pursuant to the defense of a criminal indictment or prosecution is an expense ‘reasonably related to performing the duties of the office held.’”

Citing a Federal Election Commission advisory opinion that legal fees incurred pursuant to the defense of a criminal prosecution relative to official conduct in office may be paid from campaign funds, Pryor concludes that Alabama law allows for the same conclusion stating, “Under Alabama law, as stated above, this would be a legitimate expense of the office if the conditions stated are met.”

Once again, Pryor stipulates that there are certain criteria under which campaign funds are used for a criminal defense.

Pryor concludes: “Excess campaign funds may be used by an incumbent office holder to pay legal fees incurred pursuant to the defense of a criminal indictment if the indictment is related to the performance of the duties of the office held.”

The conditions Pryor sets are a criminal indictment must have already occurred, the individual must still be in office, only excess campaign funds may be used and the charges must be relayed to the performance of the duties of the office held.

Time and again Pryor makes the condition very clear.

Yet, Speaker of the House Mike Hubbard has used approximately $300,000 in campaign contributions to pay for his criminal defense, having not met the basic requirements of Pryor’s opinion.

December 2013. He was not indicted until October 2014. This violates Pryor’s opinion that there must first be criminal indictments.

Hubbard has used campaign contributions before, during, and after a campaign. So, how does this meet the standard of excess funds as stated by Pryor?

Hubbard is charged with 23 felony counts of public corruption, from using his office for personal gain, to illegally lobbying the governor and his administration for a client and placing language into the Medicaid budget to favor another lobbying client.

How are these actions a part of Hubbard’s “performance of the duties of the office held” as stated by Pryor?

Hubbard is an incumbent and that is the only one of the four tests that Hubbard has passed under the Pryor opinion.

Individuals who have worked in the Attorney General’s Office have said, off the record, that no one actually believes that Hubbard is obeying the letter of Pryor’s opinion.

As for Woodward, he, and his attorney Albert Jordan, were convicted in federal court in January 2006, on charges of conspiracy to defraud the United States and theft of government property.