By Bill Britt

Alabama Political Reporter

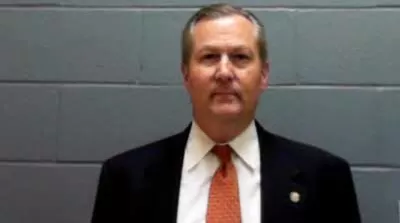

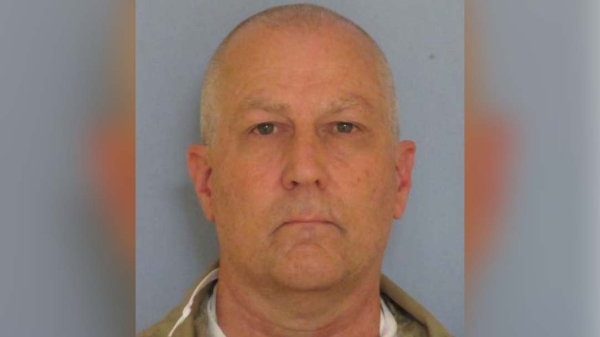

MONTGOMERY—Speaker of the House Mike Hubbard wants the people of Alabama—especially the political class and potential jurors in Lee County—to believe that his indictment of 23 felony counts of public corruption is politically motivated, and that his reelection as Speaker by the majority of Democrats and Republicans in the House is proof of his innocence.

In his book, “Controlling Corruption,” Robert Klitgaard writes, “Corruption exists when an individual illicitly puts personal interests above those of the people and ideals he or she is pledged to serve.”

This is exactly what the State’s case against Hubbard claims. Hubbard is charged by the State with using his elected office for financial gain, obtaining financial favors from lobbyists and others with business before the Legislature.

According to the State’s filings, “Eighteen citizens from Lee County returned a 23 count felony indictment charging Hubbard with six counts of using his office for personal gain, one count of voting for legislation with a conflict of interest, eleven counts of soliciting or receiving a thing of value from a lobbyist or principal, four counts of lobbying an executive department or agency for a fee, and and one count of using State equipment.”

Klitgaard states, “Corruption can involve promises, threats, or both; can be initiated by a public servant or an interested client; can entail acts of omission or commission; can involve illicit or licit service.” This again seems to fit into the pattern that the State used to indict Hubbard.

Even Hubbard himself wrote extensively on corruption in his vanity tome, “Storming the State House” citing the cases against Don Siegelman and others. Hubbard writes, “In late 2005, indictments alleging a wide variety of charges, including bribery and obstruction of justice, rained down upon Siegelman… Siegelman quickly blamed for the allegations, not upon his own wrongdoing, but upon an imagined complex conspiracy against him that included the Bush White House, the US Justice Department and the Alabama governor’s office.”

This sounds similar to the “complex conspiracy” Hubbard has alleged in his own indictments, claiming political prosecution by Attorney General Luther Strange, rouge prosecutors and liberal special interests.

Hubbard writes that Siegelman’s reasoning was, “so fantastic, unbelievable, and circuitous that I am surprised he did not include the Dalai Lama and Queen Elizabeth among those conspiring against him.”

Hubbard then derides Siegelman for seeking “the spotlight, even when his world was crumbling around him.” Meanwhile, Hubbard has taken advantage of every media platform available to espouse his own “fantastic, unbelievable, and circuitous” theory.

Recently, Hubbard appeared in Huntsville at an event attended by a “who’s who” of North Alabama politicos including, “United States Representative Mo Brooks, Huntsville Mayor Tommy Battle, Madison Mayor Troy Trulock, and many other political dignitaries…” according to a report by John Corrigan for AL.com.

In Klitgaard’s book, he recounts a story from Guatemala that he says, “illustrates the alarmingly widespread view,” of public corruption. The story is as follows:

“When in a society the shameless triumph; when the abuser is admired; when principles end and only opportunism prevails; when the insolent rule and the people tolerate it; when everything becomes corrupt but the majority is quiet because their slice is waiting…When so many ‘whens’ unite, perhaps it is time to hide oneself, time to suspend the battle; time to stop being a Quixote; it is time to review our activities, reevaluate those around us, and return to ourselves.”

Since his arrested by the State, Hubbard has gathered politicos from around the State to sing his praises, most notably, US Rep. Mike Rogers, State reps and former law enforcement officers, Mike Ball, Mac McCutcheon and Allan Farley.

Hubbard writes in “Storming the State House,” “I found myself wondering which was sadder— the steep free-fall that Siegelman had experienced since the height of his power or the fact that more than a third of Democratic voters would support a candidate who spent his days fighting serious corruption charges.”

The irony of Hubbard’s “wondering” then and his actions now, lead back to the question of what to do when? “…the shameless triumph; when the abuser is admired; when principles end and only opportunism prevails?”

Hubbard’s so-called consulting clients paid him perhaps hundreds of thousands of dollars. He acquired hundreds of thousands more in the form of “investments.” As Chairman of the ALGOP, he funneled more money into his own business interests and he voted for legislation that would give millions in Medicaid funds to his client.

Klitgaard stresses that we should not look at public corruption as a moral issue, rather “another problem to be analyzed with the tools of public policy and management.”

In 2010, the Republican super majority passed strict ethics laws as tools to manage public corruption. Hubbard now finds himself on the other side of those laws, but wants to escape the consequences of his actions.

He writes of Siegelman, “[He gave an] impassioned argument that the charges against him were part of a Republican political machine that, for some unexplained and unacknowledged reason, feared Siegelman and his influence.”

Today, Hubbard is making the exact same argument for which he condemned Siegelman.