By Bill Britt

Alabama Political Reporter

Few may know it, but the county district attorney’s of office is responsible to make sure school-age children attend school.

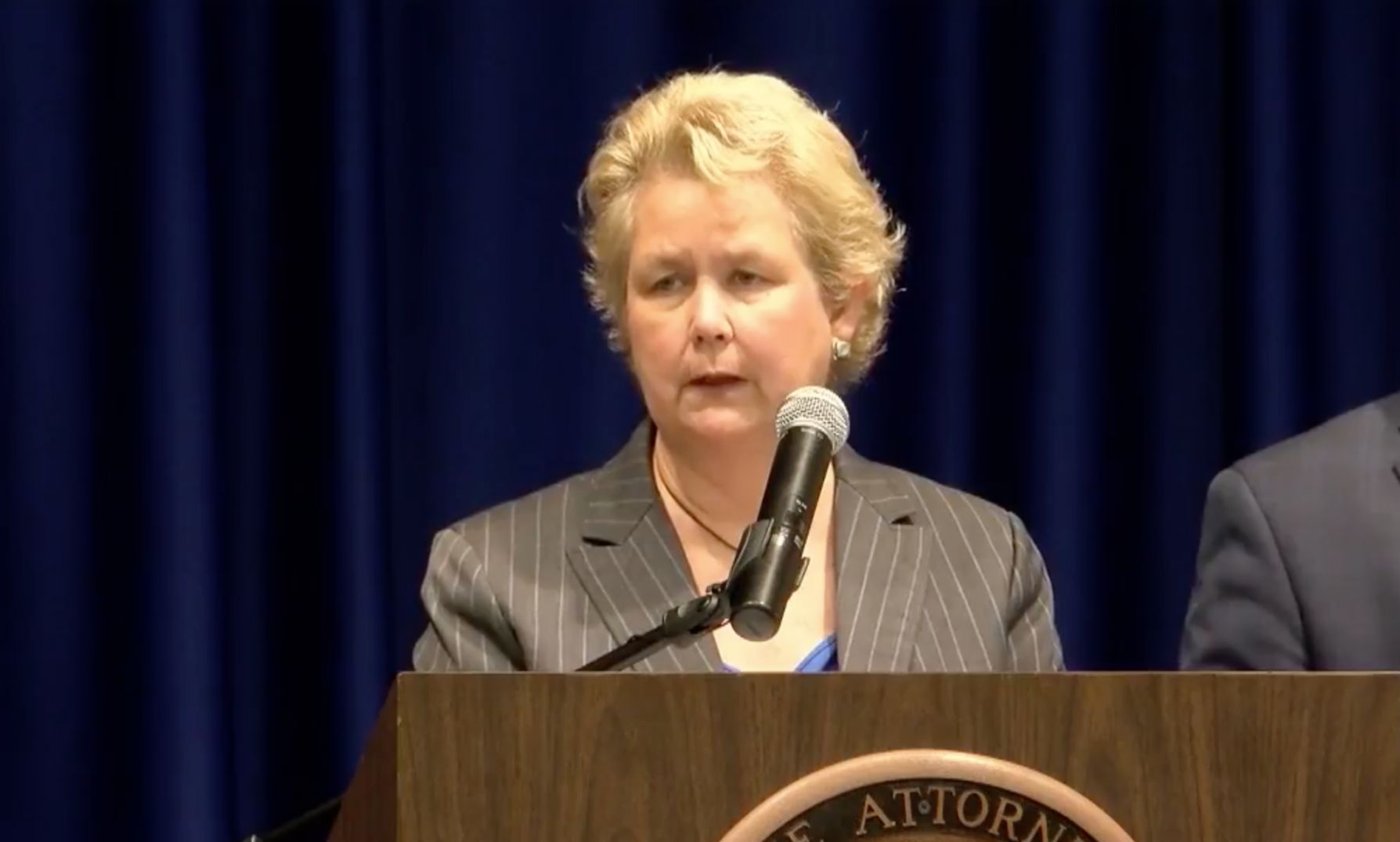

“According to Alabama law, the district attorney must vigorously enforce, the law that says, children must be enrolled in school, attend school regularly and behave in school,” says Montgomery DA Ellen Brooks. “This is the only law I have found that says it must be ‘vigorously’ enforced.”

Brooks, inspired by her fellow district attorneys in Mobile, has work hard to vigorously uphold her obligation.

This has come about through the Helping Montgomery Families Initiative.

According to the program’s materials, “The Helping Montgomery Families Initiative (HMFI) provides intervention/prevention services for suspended (but not charged) school children and their families.”

“When we first looked at the situation, it was clear to me that this law was not being ‘vigorously’ enforced, as stated by the statute,” said Brooks.

When she asked for the statistics on how many cases were on hand, Brooks was told, “We had next to none.”

“I was shocked because,” said Brooks. “I could drive down the streets of Montgomery and find kids who were obviously not in school and obviously not sick.”

Brooks agreed to head the program that became HMFI on the condition that there would be a commitment to back the program and that the resources would be made available. Brooks said she received the commitment and began the process of building the program.

“We hired a small staff mostly with social workers, people with that mind set,” said Brooks. “I wanted to keep this separate from prosecution because it gets into the family’s home and they must trust you. I didn’t want them to feel like we were there to put them in jail.”

Brooks recounts that the first hire was the key, “Andrea Edwards was the first hire, she has been the key to success,” said Brooks. According to Brooks, Edwards’ extensive background in social services, coordinating programs, planning budgets and work with people was the “right combination.”

Having buy-in from all the stakeholders Brooks believed was the only way to have a successful program.

In 2007, Brooks “established a partnership with the Montgomery Public Schools (MPS) Superintendent to create HMFI with the support of government officials and community leaders. Others involved in the program are “local law enforcement, healthcare professionals, mental health, social services, faith-based organizations, juvenile justice agencies and other organizations.”

Funding came from the city of Montgomery, “a little from the county and some from the school system.” Brooks says they also received a federal grant.

The primary focus of the program is intervention in the lives of school children who have been, “suspended from school but not charged with a criminal offense,” according to the DA’s website.

The basic premiss is that some children within the county face overwhelming odds in their daily lives that will keep them from succeeding in school.

Among them are domestic violence, drugs, gangs, homelessness, sexual abuse, poverty, and lack of basic necessities.

These obstacles many times manifest in a child missing school, behaving badly in class and other problems.

Many studies conclude that this is the beginnings of the “school pipeline to prison.”

HMFI, according to Brooks, is to identify the root of the problem that prevents a child from behaving in an appropriate manner in school.

It is also there to offer a comprehensive assessment process and a multi-disciplinary approach to assist children and their families. Then families are linked to services within the community to address their specific needs with a goal toward strengthen the family unit as a whole.

Within the program the kids who are most at risk are identified using data from school records, engaging the student and his or her family with the problems being exhibited, then referring to the family and child to appropriate agency or organization for help. The family and the student are closely followed until completion of the program. Brooks says that 85 percent of those students that are a part of the program do not have a second suspension.

A year before the program began, there were 33,000-plus suspensions and that number has been reduced by 21 percent.