By Bill Britt

Alabama Political Reporter

MONTGOMERY—The Supreme Court ruling on the Affordable Care Act has left states with an interesting dilemma. The SCOTUS while upholding the individual mandate and other key provisions of the law struck down the portion that makes the expansion of Medicaid mandatory. The law, as written, offered states a carrot-and-stick to enlarge the pool of Medicaid eligible poor. Under the court ruling the stick was taken away but the carrot remains. Now, the states may opt out of the Medicaid expansion with no penalty for doing so. The current state Medicaid program in Alabama would continue as before.

Republican lawmaker have come out in force against the ACA, Governor Bentley intoning that it is “the worse piece of legislation ever.”

Republican governors, north, south, east and west are standing firm against entertaining Medicaid expansion for now.

Other than being a good campaign strategy for the GOP, the money offered by the Medicaid expansion may prove to be, over time, an offer too good to refuse.

Speaking with several business and medical professionals who are not ready to talk openly about the program, there is a growing sense that far from being an anathema the Medicaid expansion program may very well be a big win for states like Alabama.

Small states like Alabama have built their healthcare system on the foundation of Medicaid, therefore expanding the program means growing the healthcare industry, which means good paying jobs for perhaps over a thousand Alabamians.

It is a fact that in the state, a reduction in Medicaid would results in fewer hospitals, fewer physicians, almost zero pediatric care and so on until we would reach a positive death spiral of medical services in the state and a public health crisis to paraphrase a few leading health experts.

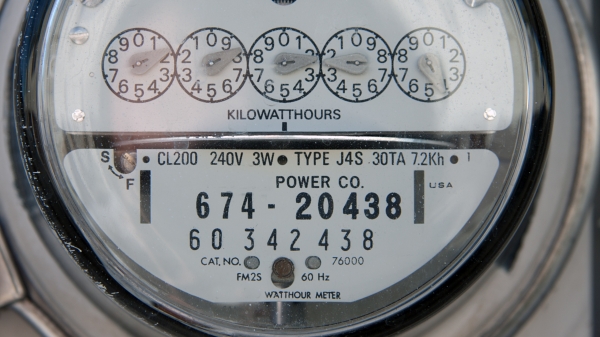

Today, Alabama receives approximately $3 dollars for every $1 dollar is spends on Medicaid. Alabama’s Medicaid program is $5,005.97 billion program with the state contributing around $620 million dollars. Once those dollars flow into Alabama’s free market economy these funds become more like $7 dollars for every $1 dollar invested. This is not only a big return on investment, if one thinks in the reverse taking those dollars out of the economy could be ruinous amount.

If the state opted into the Medicaid expansion it is estimated that around 350 thousand new people would be added to the Medicaid rolls and by extension more money flows into the state economy.

It is important to note that these new additions to Medicaid would be very different recipients. Currently there’s no requirement, for example, that states cover single men, no matter how low their incomes. But under the new plan, Medicaid would increase its eligibility limits for all adults male and female to 133 percent of the Federal Poverty Level, representing an annual income of about $14,856 for one person. This would open Medicaid coverage to childless adults, many of them uninsured, as well as families making around $30,000 a year. This is a category of the population not currently served by Medicaid. Most of those added would be healthy individuals between 19 and 40 years of age.

This is a set of the population that uses doctors and hospital rarely.

Yet, when this portion of the population-—who are uninsured, need health services and are treated the cost is passed on to those who do have insurance. Doctors and hospitals have to place the cost somewhere in the system and the burden of treating these uninsured becomes a hidden fee on everyone.

The new pool of Medicaid recipients, some say, would be a plus for hospitals and some physicians who under law must treat these uninsured citizens but receive no money for doing so.

The argument still being drowned out by political speak is that according to medical administrative professional expanding the Medicaid rolls will lower the overall cost of healthcare for everyone.

According to the American Hospital Association, nationally the uninsured left hospitals with $39.3 billion in unpaid bills in 2010.

This is seen as an unsustainable cost for hospitals to absorb or pass along.

However, lawmakers say that Medicaid has become an increasingly costly burden for states, especially during the Great Recession, and that funds to pay for the existing program are hard to find much less finding new dollars for expansion.

Countering the “states are broke” argument is that the federal government will pay 100 percent of the costs of these new beneficiaries from 2014 to 2016 and then phase down its share of the expenses over three years, reaching 90 percent still paid for by the Feds starting in 2020.

It is still unclear as to what any state will decide as to Medicaid expansion, like the first offer of the program in the 1960s there will be resistance but over time all 50 states adopted the federal plan.

The history of Medicaid itself may be an instructive example. It became law in 1965, as part of the same act that created Medicare. By 1972, every state but one had opted into the program. Arizona was the last holdout state but it had some special circumstances.

Because this is an election year, it may be difficult to separate campaign rhetoric from actual policy thinking.

It will be interesting to watch which states ask Washington for wavers giving them more flexibility or time to meet federal standards. Alabama, for now, stands resistant—-at least in speech—-to any provision of the ACA and has not applied for wavers.