Former owner and publisher of the Birmingham World newspaper, Joe Dickson, who demonstrated with civil rights heroes Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth and Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. during the Civil Rights Movement before going on to become a part of former Gov. Guy Hunt’s administration and the chair of the Alabama Personnel Board, has died at age 85.

Joe Dickson

His daughter, Jori Dickson Jordan, and his wife, Dr. Charlie Dickson, a former nursing professor at UAB for 20 years, said he died Saturday morning at his home, surrounded by family after many years battling cancer.

Those close to Joe Dickson described him as a caring father, a man of faith and a dedicated civil servant.

“It was like having an idol of some sort,” Jordan, his daughter, told APR. “He was a man that always spoke proudly of family — a man that always cared about his community, cared about people, cared about doing the right thing for people. He cared about doing the right thing for the state of Alabama particularly.”

Until his death on Saturday, Dickson served for 25 years as the chairman of Alabama’s Personnel Board. He was first appointed to the board during former Gov. Guy Hunt’s administration.

“He was fair and firm and just a pleasure to be associated with during the 14 years that I was on there with him,” said John McMillan, Alabama’s commissioner of agriculture and industries, who served on the Personnel Board with Dickson. Before he appointed Dickson to the board, Hunt — who was Alabama’s first Republican governor since Reconstruction — appointed Dickson as his assistant for minority affairs. That was during Hunt’s first term after his 1986 election.

Dickson was a longtime member of the Alabama Republican Party, serving as the leader of the party’s minority outreach program, the Republican Council, going as far back as the 1980s.

But his dedication to public service and community go back much further. Born in Montgomery March 5, 1933, Dickson, his mother and his siblings moved to the Fairfield neighborhood in Birmingham in 1939 a few months after his father died when he was 5 years old in 1938, according to a 1996 interview with the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute’s Oral History Project.

As he grew older in Birmingham, his mother worked many jobs, including a domestic, to support her family. Dickson got a job by 5th grade to help his mom and his sibling, and by 6th grade, he began selling and delivering newspapers — the Birmingham Post Herald, The Afro American, the Pittsburgh Courier, The New York Amsterdam News, The Birmingham World and The Birmingham Mirror.

They sold for 2 cents.

“I didn’t have any problems then because I was making money,” Dickson recalled in the 1996 interview. “But, what I did with the money I made, I always had to take mine home, because my mamma needed it.”

By the ninth grade, he had “graduated” from delivering largely African-American papers to throwing “the white folks’ papers.” He hired his brother and other people to help him. He was popular, too — serving as the president of his high school class at Fairfield Industrial High School.

Years later, his mother would return that money and more, when, after a two-year stint in the Army, she helped finance his first few semesters in 1955 at Miles College, a predominately black college in Birmingham. He credited his mother with urging him to pursue an education.

“My mamma gave me two $50 bills that she had tied up in a stocking,” he recalled. ‘I came out there and I paid to get in school at Miles. Then she gave me the money to buy my first books with. But, that was an agonizing thing for me to have to be pushed to go to school and I was a leader in the class.”

There he would become the freshman class president and inject himself into the heart of the growing Civil Rights Movement.

By 1955, Dickson was one of the relatively few black people who were able to register to vote because of barriers erected by Alabama’s segregationist leaders, among them poll taxes, random literacy tests, quizzes on the state’s representation in federal politics and questions like “How many bubbles are in a bar of soap?” or “How many grains of sand are there on the sea shore?”

After Dickson passed the tests — something he attributed in some part to his having grown up reading the newspaper — he helped others do the same.

“A number of people, they just wouldn’t let them pass,” he said. “It was very subjective.”

Helping other African Americans register to vote was just Dickson’s first introduction to battling Alabama’s Jim Crowe systems of segregation and discrimination. He and his fellow members of the Miles College Student Council began protesting outside Kelly Ingram Park, which was closed to black people at the time.

Their actions would grow after his graduation in 1960 and transition into the Birmingham selective-buying campaign, a 1962 act of protest that involved staggered boycotts that caused downtown Birmingham storefronts to see a massive drop in business after the black community began withdrawing their buying power. Eventually, the white-owned businesses gave in to their demands, only to revert immediately back to segregationist policies. The campaign began again.

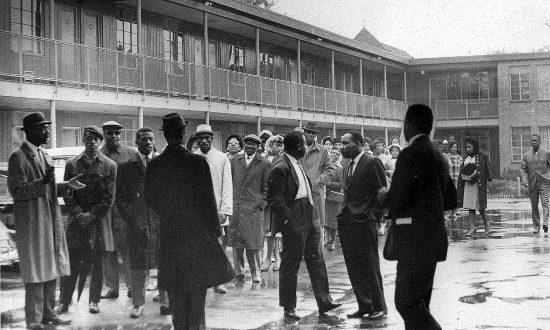

Joe Dickson, fourth from left, gathers with Rev. Martin Luther King, Rev. Ralph Abernathy and Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth at A.G. Gastons motel in Birmingham. (Picture contributed by Jori Dickson Jordan)

“We were asking these folk, if we spending our money, we want to know why can’t our women try on the hats or why can’t they try on the clothes?” Dickson recalled. “Why do you have to have two signs for the water? You got to walk all the way back down to 4th Avenue from downtown to use the bathroom. You get on the bus, you’ve got to stand there. Nobody is sitting there. They got the sign. We just wanted to know why.”

Later, he demonstrated with Shuttlesworth, King and Rev. Ralph Abernathy while working with his longtime boss and mentor, A.G. Gaston, a local black entrepreneur and businessman who provided the first meeting space for Shuttlesworth’s Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights, a group that took the place of the NAACP after it was outlawed in the state. Gaston would later pay for King’s bail after an arrest.

His wife recalled Dickson’s involvement and commitment to the movement.

“We are just extremely proud,” Joe Dickson’s wife, Dr. Charlie Dickson, told APR. “He said it’s not about how much you have. It was never about that. It was about what you can do for other people. It wasn’t about stocks and bonds. People probably think he was a rich man. He is a rich man in the sense of what he did for people.”

Dickson, who graduated with a law degree from Howard University, would go on to participate in the Civil Rights Movement as Shuttlesworth was blasted with water cannons at his 16th Street Baptist Church and King was arrested. Dickson himself was arrested at least three times throughout the movement.

Later, in the 1980s, Dickson became involved in Alabama Republican politics, leading to his time in the Hunt administration and his appointment to the Personnel Board. Having spent time as an insurance agent for Gaston’s Booker T. Washington Insurance Company, Dickson also served on the Alabama State Insurance Board and was the first black real estate agent to have a Century 21 franchise in Birmingham.

“He was one of my early heroes,” said Edgar Welden, a former chairman of Alabama’s Republican Party who was the party chief when Dickson founded the Alabama Republican Council in 1976 to represent the interest of black Republicans. “That was really the first of the modern day Republican party. Joe was one of the first trailblazers. He was one of the first black trailblazers being active in the Republican party.”

That was at a time when the Republican Party represented the interest of working black people.

“During the early years that didn’t always give him pats on the back,” Dr. Charlie Dickson said. “But he thought we should be involved in both political parties, not just one party.”

Dickson was later invited to the White House, meeting President George H.W. Bush and First Lady Barbara Bush. Years before, President Gerald Ford invited him to participate in a conference of state Republican Council groups. He was a strong voice for the black community within the party, his family said.

Among his many pursuits, Dickson helped keep the Birmingham World, a black newspaper founded in 1931, afloat after he bought the paper in 1990. The paper’s former editor, Emory O. Jackson, was a strong anti-segregationist and supported the integration of the University of Alabama. In 1989, Dickson took out a large loan nearing $200,000 to buy the newspaper from the owner of the Atlanta Daily World, C.A. Scott.

“Joe certainly believed in a free press and wanted to keep one of the oldest black newspapers going,” Dr. Charlie Dickson said. “He was very careful in who he endorsed who he supported. He wanted to get the newspaper out to the schools and the churches and to the community. And it was not an easy job operating that newspaper. He put a lot of his hard-earned money into keeping that newspaper going.”

Dickson and Dr. Charlie Dickson had eight children

His funeral will be Saturday, July 28, 2018 at 12 p.m. at his childhood church, Mount Pilgrim Baptist Church in Fairfield, Alabama.

The public viewing will be at noon, July 27.

Jordan, his daughter, who is pursuing a career in law because of her father, said her most lasting memory of her father was his faith. He read the Bible almost daily. But he also read widely, including almost any religious text about God, among them the Koran, she said.

His favorite passage was the 23rd Psalm.

“The Lord is my shepherd; I shall not want,” it reads. “He maketh me to lie down in green pastures: he leadeth me beside the still waters.”

“He believed in hard work,” she said. “He believed that if you didn’t have anything you needed a work ethic and believe in yourself and believe in helping others. Whatever you attempted to do, do the best at it. Always work the hardest to do the best at whatever you attempted to accomplish or envisioned you wanted to participate in.”