By Chip Brownlee

Alabama Political Reporter

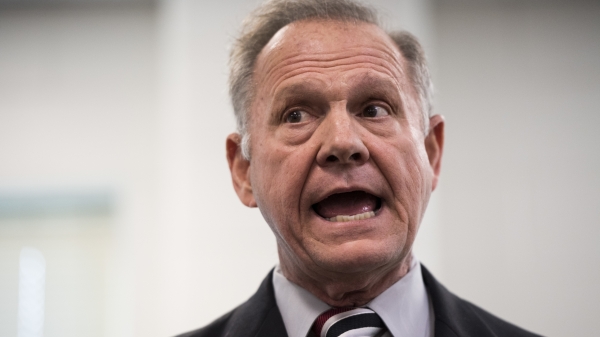

As the sexual misconduct allegations continue to swirl around U.S. Senate candidate Roy Moore, three of his spokesmen came out Tuesday to push back against the women whose accusations have threatened to capsize his campaign, claiming Moore’s first accuser Leigh Corfman had “pre-existing behavioral issues” and that other specific details from Corfman and other accusers just don’t add up.

Moore’s campaign has maintained and said again Tuesday that Moore has never met Corfman and doesn’t know her but Corfman, in an interview Monday, stood by her accusations that Moore initiated sexual contact with her when she was 14 years old, and he was 32, saying, “I wonder how many ‘me’s’ he ‘doesn’t know.'”

Ben Dupré, a former chief of staff to Moore, attempted to cast doubt on Corfman’s statements that her life spiraled out of control after she had alleged contact with Moore. Dupré said the campaign has proof that the custody hearing the day Corfman says she met Moore was predicated on the fact that, according to court documents, Corfman had “certain disciplinary and behavioral problems.”

“This was the basis for them asking that custody be changed from Leigh Corfman’s mother to her father because the father was better equipped … to deal with the already existing disciplinary problems of Leigh Corfman,” Dupré said.

The press conference Tuesday on the steps of the State Capitol comes after nearly two weeks of near-constant pressure from some Washington Republicans and the media have forced the campaign to come up with a way to discredit the allegations. Before Tuesday, the campaign had largely focused on the allegations of another accuser, Beverly Young Nelson, but the campaign switched gears Tuesday, targeting Corfman — the first of three women to accuse Moore of sexual assault.

“Her story has only been told in the vaguest of terms without any deeper investigation by the media,” Dupré said.

The campaign says Corfman’s mother transferred her custody rights to Corfman’s father on the day Corfman says she met Moore outside of an Etowah County courtroom. The campaign says her account isn’t credible because Corfman went to live with her father in a different town about 30 minutes away after custody was signed over on Feb. 21, 1979, citing court documents — which, if true, would ultimately discredit Corfman’s claim that Moore called her “a few days later,” as she said in the Washington Post report, picked her up and took her back to his home for the first time. Corfman has said Moore took her to his home a second time “soon after” the first visit. That’s when the alleged assault occurred.

“And finally, I would point out that Corfman’s father did not live in Gadsden or even Rainbow City at the time of all of this, he lived farther away in Ohatchee, Alabama,” Dupré said. Dupré also claimed that even if Corfman was with her mother at the time, her alleged pickup spot on Alcott Road and Riley Street was nearly a mile away from her mother’s home and across a major road — more than “around the corner from her house,” as she described in The Washington Post report.

It isn’t clear which home Moore’s campaign is referring to in their rebuttal because they wouldn’t take questions or how that distance changes the legitimacy or credibility of the account. The three spokesmen, Dupré, campaign strategist Dean Young and Stan Cooke, a former lieutenant governor candidate, left the press conference without fielding shouted questions from the press.

”I’ll answer questions later but not right now,” Young said, refusing to specify when “later” would be.

The Alabama Political Reporter has obtained its own copy of the court documents Moore’s campaign cited at the press conference. The documents show that custody was, in fact, signed over on Feb. 21, 1979, but Corfman would not have immediately moved to live with her father like the campaign claimed. Instead, custody didn’t officially transfer until 11 days later on March 4, 1979 — a date outlined plainly in the documents but not mentioned by Moore’s backers Tuesday. It’s a tight timeline, but it would have given Moore more than a “few days later” to call Corfman.

And according to the court documents, Corfman’s mother also had custody every other weekend beginning on Friday, March 16, 1979. The documents do say Corfman had “certain behavioral and disciplinary problems” but goes into no further detail, and the campaign did not say how that would discredit her allegations.

“There is no one here that doesn’t know that I’m not an angel,” Corfman said in the Washington Post report, referring to her home town of Gadsden.

Corfman has said the second trip to his rural Etowah County home, soon after the first, ended with Moore taking off both their clothes and touching her over her underwear. When he tried to get her to touch him over his underwear, she pulled away and asked to go home, she said, and he took her. The age of consent was 16 years old at the time and remains so today.

“I was a 14-year-old child trying to play in an adults’ world, and he was 32 years old,” she said Monday. Since she met Moore, she said she had trouble trusting men and lost her confidence. She acknowledged in the original Washington Post article that she has had some legal troubles since she says she had contact with Moore.

The conservative website Breitbart has repeated many of these same allegations, attempting to disprove what they say are “key details” of Corfman’s story. The website quoted Corfman’s mother as saying that Corfman did not actually have a phone in her bedroom, as she said in the Post story. But later in the same story, she says the phone could have easily reached her room.

Moore’s campaign has been focused on the media and the accusers since the allegations surfaced nearly two weeks ago in The Washington Post, chopping the allegations up to nothing more than a Washington establishment, liberal media attack on his conservative campaign. The Republican National Committee, the National Republican Senatorial Committee and national Republican leaders, including Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell and Sen. Richard Shelby, R-Alabama, have yanked support from Moore. The state party, on the other hand, aside from the Alabama Young Republican Federation, has chosen to stand by him — believing his denials over his accusers’ accusations.

President Donald Trump — who remained silent on the topic until Tuesday — gave Moore some reprieve from national abandonment when he cast doubt on the timing of the accusations and attacked Moore’s Democratic opponent Doug Jones for being “soft on crime.”

Moore has avoided direct questioning from the press, including local press, ducking reporters after the few press events he’s held since the allegations surfaced, and he didn’t attend the press conference his campaign called Tuesday afternoon.

The other spokesmen went on to repeat claims from the Moore campaign that Beverly Young Nelson’s story doesn’t add up, either — a task they’ve been embarked on for more than a week. The campaign has called for Nelson to turn over her only piece of hard, physical evidence, a yearbook she says Moore signed in December 1977, just days before he allegedly assaulted her. The campaign says the inscription on the yearbook is “altered,” and they want it reviewed by an analyst.

Nelson’s attorney, Gloria Allred, who herself is a lightning rod among conservative circles, has refused to turn over the yearbook, and instead called for Moore to testify before a Senate ethics committee.

Nelson told reporters at a press conference that she was 16 in 1977 when Moore assaulted her in his car behind a restaurant she worked at in Gadsden. The assault, she says, left her bruised and lying on the ground near a dumpster by where Moore parked in an unlit area.

Cooke, one of the Moore spokesmen, read statements at the press conference from two women who said they worked there from 1977-1979. The two women, Renee Kiser Schivera and Rhonda Kiser Ledbetter — who appear to be sisters from public records and obituaries for some of their family members — told the campaign they don’t remember Nelson ever working at the restaurant and don’t remember seeing Moore there as a regular customer.

The two women, whom the campaign has billed as “key witnesses,” also say Nelson would have needed to be 16 to work at Olde Hickory House. Nelson said she was 15 when she started working there, was 16 when the assault occurred and she quit the next day. In a written statement included in an email Moore’s campaign sent to the press Monday night, the women go on to dispute the closing time of the restaurant, whether it was dark out back, where the dumpsters were located, and if there would have been room for Moore to park where she says he parked. The men who spoke Tuesday said disagreements between the women’s recollections of the restaurant were “major contradictions,” which cast doubt on Nelson’s claim.

“Only now have these accusers come forward,” Cooke said. “This is an effort by these people, the liberal media, the Republican establishment, to malign the good name of Judge Moore.”

The two women weren’t present at the press conference, and the press couldn’t ask questions about their accounts.

Nelson and Corfman’s accusations are two of the most salacious among those of several women who have said Moore pursued them when they were in their teenage years. Some say Moore took them on dates and kissed them with their consent, but others allege Moore pursued them more persistently — calling their schools and showing up at their places of work when they were between the ages of 16-18. One said Moore forcibly kissed her. Another said Moore bought her alcohol when she was underage on a date.

One accuser, Tina Johnson, told AL.com she was in her late 20s when Moore grabbed her buttocks in 1991.

The three spokesmen categorically denied the allegations against Moore and said he never acted inappropriately around them. They also cited a former Gadsden police officer who disputed the New Yorker’s report that Moore had been banned from the Gadsden Mall, though they didn’t specifically respond to any other allegations except for the two more salacious from Corfman and Nelson.

“Allegations are words; they are not facts,” Cooke said. “Allegations are words; they are not indictments, and they are not charges.”

Moore is facing off against Jones in a special election that’s only three weeks away. Jones, for most of the past two weeks, has attended events and tried to stay under the radar on the Moore accusations. But a new ad-buy from his campaign focuses predominantly on the accusations against Moore, citing statements from Ivanka Trump, Attorney General Jeff Sessions and Shelby, all three of whom are among the Republicans who have broken with Moore’s campaign in the last two weeks by saying they believe the accusers.

Moore’s spokesmen said he will still win, despite the accusations.

“Fox News can put out their fake polls, and everybody else can too, but he’s still winning and he’s never been losing because the people of Alabama don’t go for what y’all are trying to sell,” Young said.